By G. L. Pease

In the early 1980s, when I first took up the pipe seriously, aging tobaccos wasn’t something many smokers talked about. Most pipe smokers simply bought their tobaccos from their local shop, smoked it, and thought little of it. In fact, older literature often suggests that tobaccos should be enjoyed relatively fresh.

In the early 1980s, when I first took up the pipe seriously, aging tobaccos wasn’t something many smokers talked about. Most pipe smokers simply bought their tobaccos from their local shop, smoked it, and thought little of it. In fact, older literature often suggests that tobaccos should be enjoyed relatively fresh.

Charles Rattray, for instance, in his Disquisition for the Connoisseur (date unknown), wrote, "Tobacco is a vegetable that lives and breathes: it does not improve by being imprisoned in an air-tight compartment." (He later retreats somewhat, writing about his mixtures that, "they improve with keeping, and the last pipeful or two of a pound of tobacco tastes the best.") Somewhat ironically, old cutter-top "prisons" of Rattray’s blends are some of the most highly coveted and revered blends amongst today’s cognoscenti.

Fortunately, I was introduced to the joys of aged tobaccos early on. Robert Rex, then proprietor of Drucquer & Sons, Ltd, (my local tobacconist’s, where I spent more free time in my university years than I did at the Silver Ball Gardens, the local pinball arcade), had put aside tins of several of the house blends, and sold them after aging for five years. The transformation was remarkable. I will never forget the first time I tasted "Red Lion" and "Inns of Court" with five years behind them. Life changing might be an exaggeration, but it certainly had an impact on the future path of my pipe smoking. Time had worked a magic that no amount of messing about with blending ever could. I was hooked.

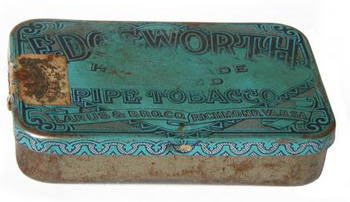

This was significant. Thirty years ago, talking about "vintage" and "aged" tobaccos would have most people looking at you like a nuthouse Napoleon. But, Robert’s aged Drucquer blends set some of us on a mighty crusade. We began pouring over the shelves of every out-of-the-way tobacconist’s we could find, hoping to find forgotten tins. We’d visit, strike up a conversation, and finally ask, "Do you have anything in the back that’s been sitting around for a while?" As often as not, the answer would be yes, and shopkeepers would disappear into darkened corners of musty back rooms, emerging with old, dust-covered tins that had "never sold very well," often offering them at a discount just to be rid of them. In markets where American aromatics were numero uno, those stinky English weeds would often languish on the shelves until they were finally removed so the space could be occupied by something that might actually sell. Bonus for lovers of the stinky stuff.

This was significant. Thirty years ago, talking about "vintage" and "aged" tobaccos would have most people looking at you like a nuthouse Napoleon. But, Robert’s aged Drucquer blends set some of us on a mighty crusade. We began pouring over the shelves of every out-of-the-way tobacconist’s we could find, hoping to find forgotten tins. We’d visit, strike up a conversation, and finally ask, "Do you have anything in the back that’s been sitting around for a while?" As often as not, the answer would be yes, and shopkeepers would disappear into darkened corners of musty back rooms, emerging with old, dust-covered tins that had "never sold very well," often offering them at a discount just to be rid of them. In markets where American aromatics were numero uno, those stinky English weeds would often languish on the shelves until they were finally removed so the space could be occupied by something that might actually sell. Bonus for lovers of the stinky stuff.

One of our little cadre discovered Garfinkel’s, in Washington DC, and more specifically, the Orient Express #11 that had been produced for them by Sobranie House some years prior. Apparently, they had a warehouse full of the stuff, so I made nice with Larry Garfinkel, and arranged a monthly shipment of eight 2oz. tins. One pound of nectar of the gods, delivered to my postbox every month for the grand sum of about $28. I’d smoke one tin, sometimes two, and the rest would be safely nestled in my linen closet. That was then. Eventually, after a couple of years, the well ran dry. I’ll never forget the day Larry called me to ask if he could send me two pounds that month. Sure, Larry. Not a problem. Why?

"I’m sorry to tell you this, but it’s the last two pounds I’ve got."

Silently crestfallen, me. Fortunately, by that point, I was fairly well supplied. I reduced the rate of my consumption, and still, almost 30 years later, am able to enjoy a tin of my all time fave once in a while, but the lesson was learned. I started cellaring everything.

Silently crestfallen, me. Fortunately, by that point, I was fairly well supplied. I reduced the rate of my consumption, and still, almost 30 years later, am able to enjoy a tin of my all time fave once in a while, but the lesson was learned. I started cellaring everything.

Today, things are a little different. It’s become fairly commonplace for people to chase after and pay outrageous prices for vintage or discontinued tobaccos, and many age their own. It’s now widely known that fine, natural tobaccos, like fine wines, often benefit from time in their respective prisons. A great blend gains complexity and richness over time, developing new aromas and character, much like the bottle bouquet of vintage grape juice. And, like wines, some tobaccos age more gracefully than others, some having the potential to carry on longer than we will.

On one end of the scale are virginias and virginia/perique blends. The natural sugar content and structure of the leaf give these ideal characteristics for long aging. I’ve smoked flakes and coins from the 1940s that were exquisite, and far from over-the-hill. Second to virginias are the oriental tobaccos, which take on wonderful fruity notes over time. I don’t know the upper limit for tobaccos dominated by orientals, but I’d guess it to be at least 30-40 years before they might begin a slow decline, and if virginias make up a high percentage of their mix, they’ll last longer, still. Burleys are generally found with plenty of virginias in the same soup, so the same situation applies. (Most aromatics don’t really change much over time, at least not in a positive direction. The stabilizers and flavorings tend to arrest the biological and chemical processes responsible for the aging process.)

Latakia, itself, doesn’t seem to fare quite as well as other leaf. After some time in the tin – some would say only a few years, which I think a little pessimistic – it loses a bit of its spicy punch, becoming softer and more delicate in both taste and aroma. To some, this might actually be an advantage, but to the true Latakiaphile, mixtures that rely heavily on the smoky stuff are likely to be considered less long-lived than those using it in more gentle measures. I’ve certainly enjoyed some wonderful examples of 30-year old mixtures, and some even older, but not all have aged as gracefully.

Latakia, itself, doesn’t seem to fare quite as well as other leaf. After some time in the tin – some would say only a few years, which I think a little pessimistic – it loses a bit of its spicy punch, becoming softer and more delicate in both taste and aroma. To some, this might actually be an advantage, but to the true Latakiaphile, mixtures that rely heavily on the smoky stuff are likely to be considered less long-lived than those using it in more gentle measures. I’ve certainly enjoyed some wonderful examples of 30-year old mixtures, and some even older, but not all have aged as gracefully.

So, how long we age a blend depends on a lot of factors, including blend components and especially personal preference. And, unfortunately, the only way to discover what blends you like aged, and for how long, is to develop a cellaring strategy that works for you. Here’s mine. It’s simple, relatively painless, and in less than a year, you can begin to explore the world of aged tobaccos, while building a nice cellar of favorites for the future.

In the beginning, each time you finish a tin of something you want to age, buy two to replace it. Write the date on the bottoms of the tins. Keep one out to smoke, and put the other away in a cool, dry place – cardboard banker’s boxes work well. Your collection will grow in proportion to your preferences; if you smoke twice as much of a particular blend over another, you’ll be adding it to the cellar at twice the rate. Doing it this way, your cellar will adapt to changing preferences, and accommodate the exploration of new territory. Once you’re smoking your aged tins, replace them with fresh ones to maintain your cellar. Simple.

When you decide to try something new, buy at least two tins. Put all but one away, and smoke that one as soon as possible. Don’t put it in a box or a drawer, waiting for it to whisper your name. Experiencing blends when young is a vital step in understanding how tobaccos will develop and change over time, and there are some blends that, honestly, are really enjoyable, perhaps even better, with the exuberance of youth bursting the seams of their tins. Besides, if you just stash it away, you might forget about it, and risk missing out on something that may well become your next top-tier blend. Remember, you’re not just building a cellar, here, but also a rich body of experiences that will enhance your pipe smoking pleasure for years to come.

When you decide to try something new, buy at least two tins. Put all but one away, and smoke that one as soon as possible. Don’t put it in a box or a drawer, waiting for it to whisper your name. Experiencing blends when young is a vital step in understanding how tobaccos will develop and change over time, and there are some blends that, honestly, are really enjoyable, perhaps even better, with the exuberance of youth bursting the seams of their tins. Besides, if you just stash it away, you might forget about it, and risk missing out on something that may well become your next top-tier blend. Remember, you’re not just building a cellar, here, but also a rich body of experiences that will enhance your pipe smoking pleasure for years to come.

As you progress in your collecting, taste often, and take notes. Since you’re buying at twice the rate you’re consuming, your cellar will grow, and within six months, you can start tasting the magic that age works. I’ve always found it a lot of fun to explore a blend at different stages of its development. Good milestones are six months, a year, two years, five years, ten.

Cellaring tobacco this way presents other benefits, as well. First, it’s a bit of a hedge against inevitable future price increases; there’s truth in the statement that pipe tobacco will never be any less expensive than it is today, so think of your cellar as a cost averaged investment, if that helps.

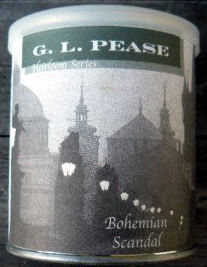

Further, in the event that something you really like disappears from the market, you’ll at least have set some aside for the rainy days. Finally, those rare vintage blends that you’ve hoarded may well be worth a significant amount more in the future than you paid for them. (I wish I had been more careful in taking my own advice with some of my own blends. When I see how much Bohemian Scandal sells for on ebay, I wish I had a thousand tins squirreled away.)

Further, in the event that something you really like disappears from the market, you’ll at least have set some aside for the rainy days. Finally, those rare vintage blends that you’ve hoarded may well be worth a significant amount more in the future than you paid for them. (I wish I had been more careful in taking my own advice with some of my own blends. When I see how much Bohemian Scandal sells for on ebay, I wish I had a thousand tins squirreled away.)

Tastes do change, of course, but that’s nothing to really worry about. For one thing, they often change back. (My tastes, as I’ve come to learn over the years, are seasonally fickle. The same thing I love in July will drive me crazy in January, and vice versa. There are very few "year round" tobaccos for me.) But, if you really turn the corner, and find your tastes completely different in the years ahead, you’ll have something to sell or trade that will more than likely have more value than what you originally paid for it. You can’t lose.

Exploring aged tobaccos is a fantastic way to extend your pipe experiences. If you’ve never done it, start now. Put some of your most beloved blends away, and revisit them in July. I’ve been using this strategy now for over 25 years, and at this point, I could smoke nothing but well aged tobaccos for the rest of my life. Not that I would. It seems somebody keeps coming up with new things to try.

Your turn.

-glp

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. |

Related Article: Pipe Tobacco Storage, By Bob Tate

Thanks Greg. Your article echos what has been my motivation

for the years of feeding the cellar. Good read.

Thanks, Fred. Glad you enjoyed it.

Great stuff, Greg! I have only recently discovered the joys of well aged leaf, and my cellar is still small, but I like the ideas you present here. The biggest fear, of course, is letting a tin go “too far” and having a most disappointing experience upon opening it down the road. Ah well…life is either a great adventure, or nothing, right? 🙂

Thank you for offering your opinions and giving us the benefit of your experience. I’ve been happily following your advice with fair success since I first encountered it in the now defunct Tobacco Aging, Storage and Cellaring FAQ website. In that FAQ you discussed the microbiology of tobacco aging; but it was very sketchy. Is there anything in print that explains how the little buggers improve our tobacco? In other words, what are we smoking in a aged tobacco that isn’t present in a fresh blend.

Whilst I agree with this Greg – and spend time trying to get the chance to agree with it more – I think it’s important to stress that we’re talking about good tobacco blends here; to paraphrase a saying from the wine world – if you age crap you get old crap!

Well put, Jim, though the description I’ve always heard was that of a more liquid bodily secretion. 😉

Señor Attic, the problem here is that I don’t think anyone really fully understands the processes involved, and if they do, they haven’t written about it that I’ve been able to find.

A great read. Thanks!

Thanks for the link (timely too, methinks!), and the sage advice.

-“Phred”

Great Article Greg and I couldn’t agree more. I recently opened a fresh tin of C&D Briar Fox (one of my favs) and a tin from ’07 and they were both good but I prefered the fresh tin vs the aged one. They even looked different.

Great article Greg.

I’ll be adding more to my cellar once I start it. Thanks Greg!

I wish I discover my Grandpa reserve, unfortunately he hadn´t made any although he was a long-time pipesmoker 🙁 But I can make happy my kids and leave them valuable heritage.

Hi Greg,

I loved your article.

Just a question though…

What do you thing about those Lock&Lock plastic jars, those which are 100% hermetic?

I’ve been using them for the short term keeping, but, how about long term, cellar?

Thanks for your advise…

I’m not a big fan of plastic containers, so I can’t say much about any particular brand. It’s easy to make plastics that either present a high barrier against water loss, or against gas exchange, but tough to make one that does both. Glass is still king when it comes to secondary storage.

Mr. Pease, once again, thanks for a great read. As an Assistant Professor of Microbiology, who is also an avid pipe smoker, I have long wondered what microbial processes are at work on the aging process of pipe tobacco. After doing some preliminary literature searches (pubmed at NCBI), I have come to the conclusion that much less is known about these processes in tobacco, than, say, microbial fermentations leading to other useful commercial products (e.g., those found in the food and beverage industries). Apparently, as these tobaccos age prior to the canning process itself, a number of microbiological events occur, involving a range of distinct species of bacteria and fungi. This is because of high water levels, that drop during production, finally reaching their lowest states prior to canning. After canning, which is what your article is really about, these microbial processes continue, somewhat abated, and most surprisingly involve an entirely different population of microbes, one encompassing more fungi and less bacteria. After sealing, of course, the oxygen levels plummet, from 20% atmospheric to levels lower than 5% eventually, over time. This is due to the metabolic process of the populations of obligate aerobes that came in with the tobacco, and are most active in the presence of high levels of oxygen. Concomitantly, as the endogenous aerobic species that came in with the tobacco gradually give way to the emergence of at first facultative (~10-15% oxygen) and then obligate (less than 5% oxygen) anaerobic microbes. The biological processes that these microbes undergo (from obligate aerobes through to facultative and then eventually obligate anaerobes) result in the production of a number of different classes of volatile molecules. As every schoolboy knows, organic molecules (hydrocarbons) are classified into four groups (sugars, proteins, nucleic acids and lipids). Interestingly, as the aging process proceeds, over years, the sugars become fully metabolized first by the aerobes early on, leaving primarily the latter three classes of molecules. The deamination (yielding organic acids) and decarboxylation (yielding volatile, smelly amines) of amino acids in the proteins and the conversion of the lipids into smaller, more volatile fatty acid chains, is what is primarily responsible for the “bouquet” upon opening the tobacco can. Presumably, during the smoking, it is the presence of these volatiles that lend the palate of the blend. The sugars that do remain, that were not accessible to the early degredation by the obligate aerobes, is what is going on with the sugar-rich Virginias. Apparently, the packing of the tobacco (plug verses loose) is what determines how much of this sugar is freely metabolized early on. To me, it would seem, a Virginia plug would retain more sugar than a loosely packed Virginia. A good starting reference might be: Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007 Feb;73(3):825-37. Microbial community structure and dynamics of dark fire-cured tobacco fermentation. Di Giacomo M, Paolino M, Silvestro D, Vigliotta G, Imperi F, Visca P, Alifano P, Parente D. Source British American Tobacco Italia, via Cinthia, 80126 Naples, Italy.

Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17142368

Anywhoo, a long winded report, but not one without some thought. Keep up the great blending and fine writing. You are appreciated!

Greg and I are about the same age, but I wish I’d learned the virtues of aging tobaccos back when he did. I used to shop at Garfinckels in D.C. too, and Bertrams as well, and could have some pretty wonderful weed in my cellar, but I don’t. I never had any smoking “pals” or mentors; I was pretty much on my own.

I accidentally found out about aging tobacco at one point. I moved, and tossed a stash of cheap drugstore bulk stuff onto the top shelf of a closet. When I moved again a couple years later, I found it. Thinking it would be nasty, I re-moistened it and tried it, to find that it was now much mellower in taste. It went quickly. I didn’t realize that this treatment would also work with GOOD tobacco, so I didn’t bother. Nowdays I don’t smoke much any more, and I sure would like to have some well-aged good blends to tap, but I don’t.

So, all I can say is take the man’s advice, and start now! -LK