G. L. Pease

This time of year, I find myself feeling a little sorry for those who live in other parts of the country. It has nothing to do with the weather, though I suppose that might be reason enough, but everything to do with the opening of the season for that magnificent regional delicacy, the Dungeness crab. Don’t take me wrong. Other crabs are delicious too, and of course, easterners have their lobsters, but the Dungeness crab is special. Its meat is firm, sweet, delicious, and the things are brawny enough to offer a more tangible reward for the not insignificant effort of divesting them of their hard, sharp shells.

This time of year, I find myself feeling a little sorry for those who live in other parts of the country. It has nothing to do with the weather, though I suppose that might be reason enough, but everything to do with the opening of the season for that magnificent regional delicacy, the Dungeness crab. Don’t take me wrong. Other crabs are delicious too, and of course, easterners have their lobsters, but the Dungeness crab is special. Its meat is firm, sweet, delicious, and the things are brawny enough to offer a more tangible reward for the not insignificant effort of divesting them of their hard, sharp shells.

Nothing is better on an early winter’s day than playing tourist, and buying a couple of these delectable crustaceans from the crab mongers along Fisherman’s Wharf who boil them in giant pots, crack their shells with a mallet, and bundle them up in butcher paper. Add a loaf of crusty Boudin sourdough, which also cannot be found anywhere else, a stick of butter, a bottle of crisp, unoaked Chardonnay, and a beach towel (eating crab can be messy business), and you’ve got everything you need for a fabulous movable feast, unique to the left coast. If it’s not raining, find a quiet place and tuck in. You can have a salad later, if you must. I know what I’m doing this weekend…

On to the Q&A.

From Eric C.: I started smoking a pipe in 2005 and quickly discovered your Briar & Leaf Chronicles, which around that time came thick and fast. When the pace of that slowed down, I discovered the old alt.smokers.pipes archives and began to dig through that. In addition to gaining a wealth of knowledge, I’ve made friends, in a manner of speaking, by reading posts of folks like Paul Szabady, Irwin Friedman, Mark Tinsky circa 1997-2001. Of course you’re all over that period there. That seemed like a really interesting time in the tobacco world: Three Nuns still had perique, Esoterica was all the rage, there were mail order estate pipe catalogues, Dunhill still ostensibly gave a damn about tobacco. Etc. And anyway, early on in that timeframe was the brief existence of the Friedman & Pease tobacco company.

This garden path introduction finally leads to my question: could you provide us with a short history of Friedman & Pease? I’m more interested in the genesis of it than the breakup. I’m also interested in which blends there eventually became in some fashion part of the GL Pease line. Aleister likely was behind Haddo’s, perhaps Fez was behind Cairo, Silk Road pretty obviously became Samarra. This seems like an interesting chapter in modern pipe tobacco history that hasn’t really been talked about much, and you’re the only one of the two who can tell it with a Q&A column.

A: It’s a bit of a distant blur, but I’ll try to recreate a little history, or at least make something up that sounds good. It’ll be fun, at least for me. Your observations, by the way, are astute. You got the evolution of those three spot on!

So, in 1998, I was on temporary disability after developing the dreaded Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS) from too many years of too many hours behind the keys in the mad world of computer science. My doctor presented me with a lengthy list of the many things I was prohibited from doing, which included a lot of the stuff that made me happy. No fencing, no martial arts, no mountain biking, no guitar playing, minimal slicing and dicing in the kitchen, and above all, no keyboard or mouse work. I’ve never been the sort to sit about twiddling my thumbs, which was probably on the list anyway, so I had to figure out something to do with myself for the next eight to twelve weeks.

One day, I was on the phone with Irwin, who was lamenting yet one more of the great old tobaccos that had gone the way of all mortality, disappearing from the market forever. In an instant, I recalled the pleasures of working with tobaccos during my time at Drucquer & Sons, and mentally checked the doc’s damnable list. I didn’t recall any mention of tobacco blending as being taboo…

"Let’s start a new brand!" I could see the product in my mind’s eye – the label design, rows of tins on tobacconists’ shelves, happy pipers puffing away on blends that I would develop. That was it. A moment of impetuousness, and it had to be done. Then came phone calls, research, finding suppliers that would sell to a couple of upstarts with a silly idea. It took on a life of its own, really. Like an avalanche. It’s all I thought about. Nothing would stop it.

Within a week or so, my kitchen was filled with bags of blending leaf and big plastic tubs. My cutting board was adapted to hold the newly purchased tinning machine, a hand-operated model that took 21 turns of the crank to seal the tin. Figuring that even though it wasn’t on the doctor’s list, turning a crank 21 times for every tin probably qualified as repetitive motion, so I adapted it to modest automation using an electric drill and a little ingenuity. I resurrected some of my old blending experiments from years before, and the first new creation was Silk Road, based loosely on a blend I’d done for Drucquer’s called Sublime Porte, and which later evolved into Samarra.

Then came Aleister. I’d read somewhere that Aleister Crowley smoked straight perique soaked in rum. I tried it. After recovering from the ensuing delirium, and weed-eating the newly grown carpet of hair off my chest, I recognized that there was something there, if I could tame the beast. Working with burleys, virginias, and a bit of unflavored black cavendish, I developed a unique and, I think, really delicious mixture, and named it after its source of inspiration. I think Oasis was next, a lighter style latakia mixture.

I went to work with a borrowed Mac and an early version of Illustrator designing the labels, found a printer who would do short runs, ordered cartons of tins, pull-tops, plastic overcaps and glue sticks. Within a few weeks, it looked like there might be a real product. Irwin went out to solicit sales from local tobacconists who were all eager to help get things started. We sold just under 100 tins the first month.

Over the next 18 months came Fez, Fool’s Cap, Templar, Inverness, a few others, and ultimately, Winter’s Tale, a limited edition mixture of house-made (literally) black virginia, latakia, and a bit of perique. In 1998, I did about 250 tins of it for November release. In 1999, it was a whopping 800. During that time, the brand enjoyed some small success, but I never saw a penny from the efforts, and knew changes had to be made. As is so often the case with business relationships, the partner and I didn’t ultimately see eye-to-eye on the way things should go, so I made the decision to dissolve the company. As part of the dissolution settlement (sounds like a divorce, yes?), I agreed not to use the formulae I’d developed, or the names, so I had to start fresh, using a few of the old blends as inspiration for new ones. I used the opportunity to make some improvements, using better leaf that I now had access to, and the experience the previous 18 months had offered.

In March of 2000, G.L. Pease was born with Cairo, Samarra, and, I believe, Renaissance which grew out of something I was working on during the F&P days. Haddo’s Delight was added later that year. After some wonderful and fruitful conversations with my dear friend Craig Tarler, a discussion that had started during the F&P days, I gradually moved manufacturing to C&D. The rest, as they say, is history. Needless to say, I never went back to the computer industry, and my CTS miraculously disappeared. It’s been a long, strange trip since those early and very humble beginnings; I don’t regret a second of it.

Marshall J. writes: I enjoyed your insights on the contribution of the shank to flavors and just read (and enjoyed) your comments on BoB about bowl passing gas(es and fluids).

Your experience with the inserting a SS tube in the shank is similar with my observations on smoking a Kirsten and Viking metal shank pipe. The smoke in these pipes is dry and cool but the flavor is muted compared with a brier. My opinion is that the shank contribution is good while fresh but can get overwhelmed after over use, what ever that is, and the pipe turns sour.

I have been curious about the resting time for a briar. I smelled the bowl each day after use. The odor was acrid in the beginning and after 3 days it had mellowed out to OK. BTW, Steven Books’s "Natural" blends have a much less acrid odor and the bowl recovers faster than 3 days. I am guessing that the shank takes more time to dry out etc and so most pipers wait for 7 days.

PS. I have tried to find a "blend" called "Old Chippewa Straight" that was sold by the Campus Smoke Shop at Bancroft and Telegraph about 1964. Did you ever see that one?

A: I’ve been chatting with a few friends about this. It seems your observation that some tobaccos require less resting of the briar after smoking than others is a fairly common experience, and it makes sense that more natural leaf will result in less non-water moisture finding a home in the bottom of the bowl, and especially in the pipe’s shank, therefore requiring less time to "dry out." Another thing that seems to follow is that the gradual oxidation of those deposited distillates seems to soften their potentially acrid nature, hence the smoother, purer taste that results from a well rested pipe. How long a pipe needs to rest between smoking sessions depends on a lot of factors, including the briar itself, the tobacco being smoked, the habits of the smoker, and how tolerant the smoker is to the harshness of these byproducts; some can’t tolerate it, and others don’t seem to mind it very much at all. Once again, ask 100 pipe smokers a question, you’ll likely get at least 101 answers. Different smokes for different folks.

When I was at Berkeley, the Campus Smoke Shop had become Whelan’s. They had a great magazine selection, an interesting array of fairly inexpensive pipes (I still have a lovely GBD New Era squat bulldog I bought for about $12 -(how times have changed!) and some decent shop tobaccos, including one called Black and Gold that I quite liked, but I don’t recall Old Chippewa Straight. Maybe one of our readers can shed light.

Kevin dances on his keyboard in tiny little tap shoes to ask: Are all tobaccos fermented at some point in their processing? Are any fermented more than once? Does pressing cause fermentation?

A: The short answer is yes, they are, but it’s a bit more complicated than that, as different tobacco types will undergo different types of fermentation at different points along their journey to our pipes.

All tobaccos begin their post-harvest life with curing, which is primarily a controlled drying process designed to get the tobacco into a state where it won’t further decompose. (I discussed curing methods in a previous column.) Once cured, tobaccos are still quite harsh, and not ready for smoking, so they undergo a period of fermentation to eliminate some of the harsher nitrogenous compounds, develop additional flavor and aroma, and to stabilize the leaf for storage. Finally, the tobacco is aged until it’s ready for use. This is the point at which blenders will usually accept the leaf.

Once blended and tinned, additional fermentation will take place. There’s much talk about aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and both play a role in what’s going on in the tin. One common misconception is that vacuum sealed tins automatically undergo anaerobic fermentation, and this isn’t correct, as there is still plenty of air in those tins. The manufacturer puts the tins in a partially evacuated chamber which draws the lids down tightly and holds them in place until the gasket around the lid, softened from heating, cools and seals the tins.

Then, as aerobic fermentation takes place, oxygen is used up, and CO2 is evolved, ultimately halting the process, and allowing anaerobic fermentation to take place. This combined process will take place in a vacuum sealed tin just as it will in a tin sealed at atmospheric pressure, though the rate at which these changes take place will be affected by the amount of oxygen in different packages.

Pressing does not really "cause" fermentation, but as the tobaccos are put under extreme pressure, redistributing their moisture and soluble flavor components, there is very little oxygen left in the blocks, especially at their cores, so in addition to the the melding and integration of flavor components of the different leaf in the blend, anaerobic fermentation will tend to begin much earlier in the process. Once the blocks are cut and tinned, a third round of fermentation often takes place, along with other reactions thanks to the new environment. Of course, once the tin is opened, some volatile elements dissipate, and fresh air is introduced, resulting in the process changing yet again.

For those still reading, we’ve reached the end of another installment. Got burning questions? Submit them here! Got comments? Submit those down below. We love hearing from our readers.

-glp

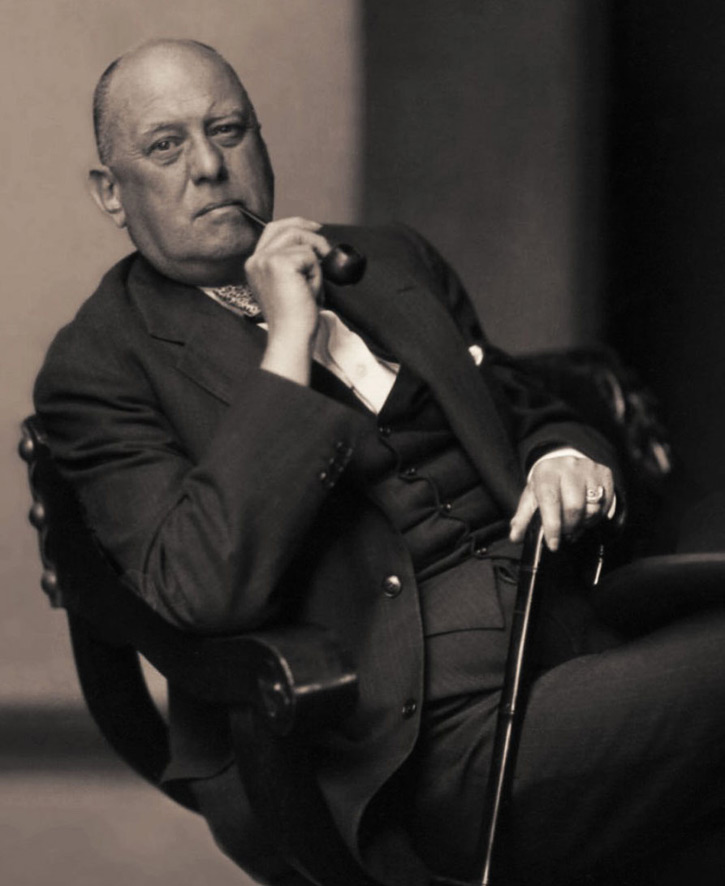

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. See our interview with G. L. Pease here. |

Oh my gosh! My secretary wondered what in the world I was doing in my office as I was in tears laughing over the delirium and chest hair comment!

The crab salad (on Boudin sourdough bread of course) that may be purchased on Fisherman’s Wharf is simply one of the best things that I have ever eaten. Is it made from your beloved Dungeness crab?

Also, Boudin sourdough bread is sold in the Midwest (and eagerly purchased by me) at Costco.

That crab salad would indeed be made from the delightful Dungeness. As for Boudin being available in the mid-west, I’ll take your word, but you certainly cannot get it fresh and warm from the bakery! (Do you detect just a wee bit of gloating? 😉 )

Yet another fine article, Greg!

I live in Dungeness, WA, a five minute walk from the Dungeness Bay.

There’s nothing like a bowl of Odyssey after a dinner of Dungeness crab. Our next door neighbor has a boat and all of the equipment it takes to hunt the wiley Dungeness crab. When we see his truck pulling his boat back home, we know there are a few crabs on there way into our pot.

You bring the crusty Boudin sourdough, I’ll supply enough crab to put all of us into a delightful delirium.

Denman

Many thanks for a fine article!

Always interesting and informative.

Another good job!

Great article, Greg. Nothing like learning something with humor injected.

I love reading these articles! Thanks for the brief history of F&P.