Alan Schwartz

Because of the Italian Renaissance of the pipe is in its full, PipeSMOKE made a pilgrimage to Italy. We started in Rome and continued a peregrination around the country northward to visit the industry saints or sinners (depending on whom you ask), and hand carvers in smaller workshops, as well as large factories. But, with so many pipe manufacturers and an enormous range of stylistic variations, we decided to acquaint or readers with the pipe culture of Italy and look at the "schools" of pipe making. Rather than trying to list everyone or trying to establish hierarchies we tried to find some unifying ideas to help understand this recent phenomena. Because it is nature and nurture in Italy to argue ones opinion vehemently and passionately, but without personal animosity, we must emphasize that the ideas expressed below are those of the individuals interviewed and not necessarily those of this magazine.

Because of the Italian Renaissance of the pipe is in its full, PipeSMOKE made a pilgrimage to Italy. We started in Rome and continued a peregrination around the country northward to visit the industry saints or sinners (depending on whom you ask), and hand carvers in smaller workshops, as well as large factories. But, with so many pipe manufacturers and an enormous range of stylistic variations, we decided to acquaint or readers with the pipe culture of Italy and look at the "schools" of pipe making. Rather than trying to list everyone or trying to establish hierarchies we tried to find some unifying ideas to help understand this recent phenomena. Because it is nature and nurture in Italy to argue ones opinion vehemently and passionately, but without personal animosity, we must emphasize that the ideas expressed below are those of the individuals interviewed and not necessarily those of this magazine.

ROME: Shopping for Style and Culture

ROME: Shopping for Style and Culture

Fincato is a pipeshop dating to 1932, and located in the old Roman center near the eternal Pantheon and the ephemeral government offices. Here, Fauso Fincato holds court:: this is his empire. The shop’s street level features well-stocked display counters and wall racks with all the standard brands of tobacco and pipe. Up a flight of steps is a lounge-like showroom and museum outfitted with arm-chairs, couches, coffee, magazines, and tobacco humidors for a fill. Here, customers who drop by for a smoke, a chat, a sample, or a purchase find Fincato’s best offering – his personal attention.

A universally acknowledged spokesman for the Italian pipe world and publisher of the distinguished magazine, SMOKING, this suave, silver-haired gentleman has a style that would serve well in the diplomatic corps – discreet and direct, but with an agenda. He says, for example, that Italian pipe smokers mostly don’t buy what is commonly thought of as an “Italian” pipe – a large, freehand, fancy shape with baroque form or rococo ornamentation. What they like are the classics – standard. shapes that are time-honored but modified by the pipemaker’s artistic sensibility “As with great big cigars, huge pipes in everyday use are moments of exhibitionism. The pipe will remain, as it always has, classic. It promotes the image of elegance and refinement,” Fincato explains as he lights up a well- used Savinelli Golden Jubilee with a billiard bowl, a bit taller but slightly narrower than the sandblasted, thinner-shanked Dunhill billiard I am carrying with me.

We admire the Savinelli and the Dunhill, in the universal show-and-tell pipe lovers use to get acquainted, along with a Peterson billiard with silver mount and spigot that I withdraw from my pocket. “I can see that you like the classics too,” Fincato remarks. “Look at the perfect form, the balance between bowl, shank, and mouthpiece. This Savinelli is the classic Italian billiard; yours are the traditional English or Irish versions,” he points out.

In fact, most of the pipes Fincato displays in his upstairs area are classic and elegant, clearly, at home in a polished, urbane setting. “A pipe is something to carry in the pocket, part of the equipment of a gentleman. Novelty pipes sensa anima (without spirit) don’t create their own future, but all of these classics do,” Fincato opines. Creating the future is part of what the Italian pipe culture is about, but to do so it stands on the shoulders of the past.

This day, we are Fincato’s luncheon guests at the Circolo della Pipa (Circle of the Pipe), housed in a 15th century villa that belonged to a Vatican official, and probably was occupied by the painter known as “Raphael” (Raffaello Santi, 1483-1520). The Circolo, self designated as "associazione culturale," a pipe club composed of the Roman noblesse oblige, uses this elegant little villa, high up on one of the city’s seven hills, as a luncheon and dinner club, and as a gathering place for the members to meet for a convivial smoke, drink, card game, or chat.

This day, we are Fincato’s luncheon guests at the Circolo della Pipa (Circle of the Pipe), housed in a 15th century villa that belonged to a Vatican official, and probably was occupied by the painter known as “Raphael” (Raffaello Santi, 1483-1520). The Circolo, self designated as "associazione culturale," a pipe club composed of the Roman noblesse oblige, uses this elegant little villa, high up on one of the city’s seven hills, as a luncheon and dinner club, and as a gathering place for the members to meet for a convivial smoke, drink, card game, or chat.

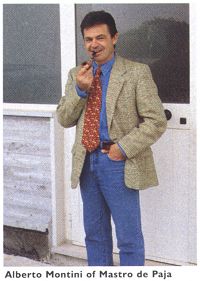

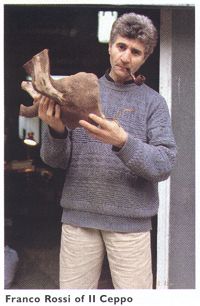

A preference for the pipe, fine wines, and gourmet food unites Circolo members, and they discuss their passions over a meal, as a preamble to smoking (it is considered brittafigura – bad form – to smoke while others eat). A wide range of topics are discussed and argued: Is Ascorti the best designer of the Como school? Is it true that Radice is his cousin? Does Savinelli still uphold the old standards? Is Brebbia shifting away from classicism? Can you really classify the pipe carvers of Pesaro as a school with Giancarlo Guidi (Ser Jacopo) as their leader? What about Bruto Sordini (Don Carlos)? Are his pipes successful in the U.S.A.? Isn’t Franco Rossi (11 Ceppo) a true classicist? Do Americans still like Alberto Montini’s Mastro de Paja? Is Ardor well known in the States? Besides Aldo Velani and Thomas Cristiano, are there many brands of Italian pipes exported to America but hardly known in Italy? A lot of pipe knowledge here, and boundless curiosity.

After the meal, fine leather pouches emerge from pockets or the small leather handbags so many Italian men carry, and are passed around for approval or sampling. Treasured pipes surface and are examined. The air is filled with fragrant aromas of mostly natural English-style mixtures and Virginias, and a few of the lighter Dutch and Danish cavendish blends. A bond is formed through the act of dining and smoking together in this unabashedly men’s world of pipes, good food and drink, and fragrant coffee.

Back in everyday Rome, we visit the shop and workshop of Becker and Musico, just around the corner from the Trevi Fountain (as in “Three Coins in the one of the most densely tourist packed areas in Rome. Here, Paolo Becker, the son of the late famed pipemaker Federico (Fritz) Becker, and Massimo Musico work at making and repairing pipes. For pipe lovers it’s a respite from the outside world, again with comfortable seating, magazines, tobacco samples, and glorious pipes. Massimo is known as one of the best restorer/ repairmen in Rome, and even performed “emergency” surgery on a damaged pipe in my travel pack.

Back in everyday Rome, we visit the shop and workshop of Becker and Musico, just around the corner from the Trevi Fountain (as in “Three Coins in the one of the most densely tourist packed areas in Rome. Here, Paolo Becker, the son of the late famed pipemaker Federico (Fritz) Becker, and Massimo Musico work at making and repairing pipes. For pipe lovers it’s a respite from the outside world, again with comfortable seating, magazines, tobacco samples, and glorious pipes. Massimo is known as one of the best restorer/ repairmen in Rome, and even performed “emergency” surgery on a damaged pipe in my travel pack.

Becker’s work created a large following in the U.S. during the 1970s and ’80s for large freehand shapes, mostly with a rusticated finish, and rare, perfectly grained, smooth pipes. These days Becker still carves the freehands but is emphasizing a more classic line of medium-sized pipes with a British look and an Italian flair. “With so many younger professional men getting interested in pipes,” he says, “most of my sales are [pipes] in the medium-size range and are intended for daily use, not for collecting."

A few streets away, Augusto Ain the Wuof. About herrascenzo’s spartan shop, Regali Novelli, has the largest selection of Castello pipes this side of anywhere. And so it should, because Parascenzo is the designated distributor of Castello. Here the pipes are larger, more freehand than we’ve seen at the other shops and are “More for the Americans and Germans,” Parascenzo tells us. This street-level store is built for speed, not comfort, a far cry from the cultivated and leisurely connoisseurship promoted by Fincato or Becker & Musico. Pipe culture is somewhere else, but the Castello selection here is fabulous. Choice reigns, not elegance.

But Rome is for buying: the real “schools” of artisans, their workshops, and the larger factories are elsewhere.

Pesaro:

Pesaro:

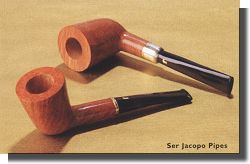

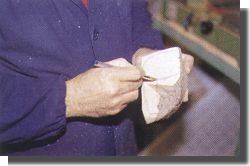

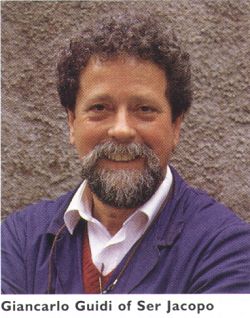

Northeast of Rome, in an Adriatic beach resort and shipping port named Pesaro, Giancarlo Guidi of Ser Jacopo, a master pipemaker generally regarded as the chief architect of the Pesaro style or “school,” shows us around his laboratorio (workshop) and offers a cogent explanation of the different schools. “Pesaro is artisan,” he says. “We all started by ourselves or in small groups of two or three to make pipes 20 to 30 years ago. We had only a few machines for drilling and polishing, but did all the cutting and shaping by hand, or at most with a lathe to turn the pipe while we shaped it with tools.

“Milan and Varese, on the other hand, had the industrial tradition of the north of Bruto Sordini of Don Carlos Italy,” he continues. “You can trace the anima (soul, spirit) of Brebbia and Savinelli back to the great Fratelli Rossi factory near Varese. They made up to 50,000 pipes a day at the beginning of the century. That’s 12 million pipes a year from one factory! When Buzzi (Brebbia) and Savinelli started together, and then split up, that was their tradition. To this day the factory concept drives both of their thinking and shows in their classical shapes, which I think are the best in the world. Even though they do make some very fine hand-carved pipes, they start conceptually with what can be made by machine and go on from there. The pipemakers around Gavirate-Ardor, Talamona, and others, are in the Savinelli-Brebbia orbit.”

“What about Castello?” we ask, intrigued by Guidi’s opinions and urging him to continue.

"Castello started the new Italian pipe. When Carlo Scotti began the company right after World War 11, his concept was to make radical innovations on standard forms and to make only the highest quality [product] for a small market of connoisseurs who could afford to pay the price. He used a very basic machine to cut the rough forms for consistent shapes, and then completed all the rest by hand. Great pipes, beautiful shapes. Of course there were also freehands, but only a small percentage. Ascorti and Radice originally worked for Castello, and when they went out on their own they carried out a similar idea: variations on classical themes, as seen in machined pipes. For that kind of artisan work, I think that Roberto Ascorti is one of the best pipernakers in the world today.”

Asked about the difference between the northern schools and Pesaro, Guidi responds, “We started as self-taught artisans, who then learned from each other. Some had worked in the northern factories, others spent time in Livorno with Cesare Barontini (a major supplier of raw briar for the Italian pipernakers and a large scale contract manufacturer of pipes to the world market.) I was self taught. As a university student of art and design, I started to make my own pipes and then, because there was no work in my field, decided to do that for a living. The only machines I had were a saw, a lathe, and a sander. And that’s all I have now, although more of the same.”

Asked about the difference between the northern schools and Pesaro, Guidi responds, “We started as self-taught artisans, who then learned from each other. Some had worked in the northern factories, others spent time in Livorno with Cesare Barontini (a major supplier of raw briar for the Italian pipernakers and a large scale contract manufacturer of pipes to the world market.) I was self taught. As a university student of art and design, I started to make my own pipes and then, because there was no work in my field, decided to do that for a living. The only machines I had were a saw, a lathe, and a sander. And that’s all I have now, although more of the same.”

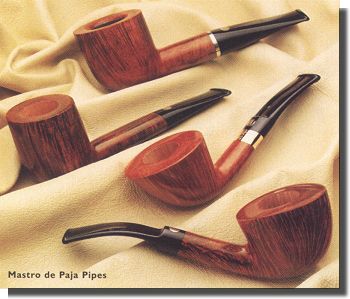

Guidi’s first company wasn’t Ser Jacopo; it was Mastro de Paja, which he started in 1970. In 1982, Guidi left Mastro to his partners and started Ser Jacobo, where he continued to make large and over-sized “organic” shapes determined by the grain of the wood, and implemented elaborate ornamentation at the joint between the wooden shank and the Lucite stem. “In my exploratory phase with Mastro and then in the new company, I made sculpture, not pipes that were comfortable and smokeable. Then I returned to the classics, as a type of maturity. I search for thematic material in folklore, art history, and pipe traditions,” Guidi explains.

One of the major accomplishments of Giancarlo Guidi is indirect: whether in the earlier phases of his career or the most recent, most of the Pesaro pipernakers have come under his influence. Either they worked for him or learned from him as apprentices. For example, Bruto Sordini originally studied medicine but was entranced by pipernaking, and learned the basics from a local carver in his native town of Cagli, in the mountains an hour west of Pesaro. Guidi supplied briar and the two became friends. Then Guidi asked Sordini to join him when he started Ser Jacopo in 1982. Since 1988, Sordini has made his own Don Carlos pipe in a purpose-built workshop in Cagli.

With a spectacular view of the mountains through the huge windows that flood his workshop with light, and opera blasting on his stereo, Sordini, his wife Rosaria, and one assistant make some of the finest examples of large freehand classics we’ve seen from the Pesaro school. Guidi’s influence is evident in the clean lines and balanced proportions, with surprising angles and curves, although the Don Carlos pipes are generally larger than his mentor’s. Sordini also likes to add substantial ornamentation to the mouthpiece/bowl joint, like Guidi. Sordini’s pre-pipe medical studies show too, with his scientific background leading him to invent and patent a carefully researched water filtration and moisture removal system in his “Hydra” pipe. His early apprenticeship with the local craftsman, along with the rugged local geography, also influence the outdoor character of his carving.

A more subtle Guidi influence is on Il Ceppo. According to Franco Rossi, who heads the company now, his sister and co-worker Nadia founded the company with her husband, master carver Georgio Imperatori, now retired. Imperatori worked with Guidi in the early days and started Il Ceppo when Guidi started Mastro. Somewhat younger, Franco Rossi started at Mastro after Guidi had gone on to form Ser Jacopo, and learned the Guidi style of pipemaking, the style Mastro still uses today. Later, Rossi joined Imperatori at Il Ceppo, and eventually took over.

Rossi, an amiable man who instantly makes you feel that you’ve known him forever, has a passion for classics, all hand-turned, but with differences in proportion from the traditional shapes. An unusually wide shank will flow from a narrow bowl, or vice versa. Innovative silver bands adorn the shanks, and the mouthpieces are jewel-perfect in size and proportion. “The classical mode comes from Imperatori,” Rossi says, “but the freehands have the flavor of Montini’s Mastro, courtesy of Guidi."

Rossi, an amiable man who instantly makes you feel that you’ve known him forever, has a passion for classics, all hand-turned, but with differences in proportion from the traditional shapes. An unusually wide shank will flow from a narrow bowl, or vice versa. Innovative silver bands adorn the shanks, and the mouthpieces are jewel-perfect in size and proportion. “The classical mode comes from Imperatori,” Rossi says, “but the freehands have the flavor of Montini’s Mastro, courtesy of Guidi."

The next stop on our journey is Mastro de Paja, where Alberto Montini shows us his immaculate factory, where five micromanaged pipernakers are kept busy. “Mastro de Paja is still producing the freehand style pipes the company pioneered in the early days, except that the sizes are a bit smaller," Montini tells us. One mandated innovation here is that the finishers work on different shapes randomly sorted to keep their attention fresh and to avoid the numbing repetition of looking at the same pipes all day long. Montini, a keen observer of business trends, notes that he too is moving toward moderate sized classics in his 1998/99 collections. “The younger men want smaller, less obvious pipes,” he says, “and we want the younger men as customers. This is a market-driven business.”

Whether the members of the Pesaro school acknowledge or deny it, their history echoes Giancarlo Guidi’s own. All of them run small artisan workshops that they started, with difficulty, when they decided to go it alone, and all use limited machinery. All hire workers who can carry out any phase of pipernaking, some of whom, in fact, split their time among the different makers’ workshops, as the season and production schedules demand. All, moreover, bring a high degree of similarity in method and style to their work, with the distinct differences that personality dictates.

The Pesaro pipernakers have one other thing in common: they all have a prominently displayed picture of the world-renowned tenor Luciano Pavarotti smoking one of their pipes. A passionate pipe smoker, Pavarotti has a home nearby on the Adriatic shore, and homage paid to him with a gift of a specimen briar from one of the pipe maestros begets a photo posed with that pipe. And we are assured that Pavarotti smokes them all.

|

TO BE CONTINUED: Join PipeSMOKE next issue for the second part of our Italian pipe journey! We travel north to Milan, Cantu, Cucciago, Varese, Lake Como, and Lake Maggiore, with visits to Savinelli, Ascorti, Radice, Castello, and Brebbia. Learn which major pipe maker disagrees with Giancarlo Guidi! Visit Savinelli’s famous shop! Drive Italian-style on the Autostrada! Eat pizza near the Duomo! Feel your eyes burn in Milan’s smog! Discover how Brebbia generates its own factory electricity! Decide if the Italian-French opposition in WW II was caused by the closing of Fratelli Rossi! Learn the truth about the Savinelli-Brebbia rivalry. Watch Ascorti make a pipe! Meet Alberto Paronelli, keeper of the flame in the most unusual pipe museum in the world! Stay tuned, and don’t touch that dial! |

PipeSMOKE – Winter 98/99

Very cool. Love the history behind the names. Would love to visit Italy and some of those shops, especially the ones where you can sit and smoke, and chat

It certainly would be s treat to visit some of the shops and factories in Italy. Great read!

Very good read! Learned a few things!!

Very informative.