Alan Schwartz

I. Cultural Icons – In Giancarlo Savinelli’s office, just around corner from the famous Savinelli shop in the heart of Milan, the ruggedly good-looking great grandson of the founder, dressed fashionable in a light-colored suit with a dark blue shirt, designer tie and handmade booths argues was the analysis of Italian schools of pipemaking developed earlier in this story [see PipeSmoke, Winter 98/99]. His doctorate in political science has trained him to be a cogent arguer always ready to document his thesis "There aren’t three schools, only two: the industrial, and the artisan. The first is the factory tradition and the second is the Pesaro school of Ser Jacobo, Mastro, and the others.

I. Cultural Icons – In Giancarlo Savinelli’s office, just around corner from the famous Savinelli shop in the heart of Milan, the ruggedly good-looking great grandson of the founder, dressed fashionable in a light-colored suit with a dark blue shirt, designer tie and handmade booths argues was the analysis of Italian schools of pipemaking developed earlier in this story [see PipeSmoke, Winter 98/99]. His doctorate in political science has trained him to be a cogent arguer always ready to document his thesis "There aren’t three schools, only two: the industrial, and the artisan. The first is the factory tradition and the second is the Pesaro school of Ser Jacobo, Mastro, and the others.

What about Castello Ascorti, Radice, Ardor, and the other smaller producers north of Milan, not to mention Brebbia, Savinelli’s major competitor? "Luciano Buzzi’s father Eneo (Brebbia) and the mine started together, so that so that is the industrial tradition he says Savinelli was responsible for changing the image of the Italian pipe by elevated it, and only then was Carlo Scotty Castello able to specialize by using the machine made models as a launching point for handmade variations. Ascorti and Radice come direct from the Castello tradition."

Giancarlo explains that, with few exceptions, the northern makers have developed their images from industrial models. The Pesaro school is baroque, ornate, and owes it’s concept to Danish handmade pipes of the 1960s and that mode sometimes influences northern pipemakers a bit. But mostly it is the "series" pipe made in factories, that conditions the northern school’s work. The school includes pipemakers Ascorti, Radice, Castello, and, around Gavirate, where Savinelli established his factory half a century ago, companies such Ardor, Talamona, and Molina. The pipes produced by these makers have a cleaned-line aesthetic, only baroque when they want to imitate.

Giancarlo explains that, with few exceptions, the northern makers have developed their images from industrial models. The Pesaro school is baroque, ornate, and owes it’s concept to Danish handmade pipes of the 1960s and that mode sometimes influences northern pipemakers a bit. But mostly it is the "series" pipe made in factories, that conditions the northern school’s work. The school includes pipemakers Ascorti, Radice, Castello, and, around Gavirate, where Savinelli established his factory half a century ago, companies such Ardor, Talamona, and Molina. The pipes produced by these makers have a cleaned-line aesthetic, only baroque when they want to imitate.

"It’s also in the character of the people," he says. "The northern mentality has a work ethic conditioned by factory culture and strong notions of community organization. Without that, industry is not possible. The south [in which he includes Pesaro] is more individualistic, anarchistic, and creative. It’s a question of sensibility." Regional bias is strong in Italy.

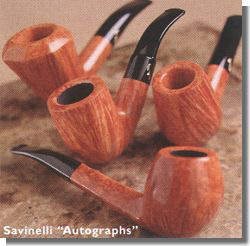

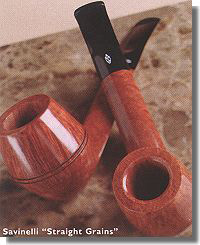

Giancarlo defines Savinelli’s company culture as classic factory production. Castello, he says, moved away from that by producing fewer models and finishes in more individualized and somewhat larger shapes. Savinelli divides his production these days into the "Classic" series and the "Autograph" fine of unique handmade models. He believes that Castello and the other makers who grew out of Castello are midway between. "It starts with the machine and develops from there," he comments.

According to Savinelli, northern Italy was dominated by one major pipe factory at the beginning of the 20th century: Fratelli Rossi (Rossi Brothers), of Varese, with 900 workers producing up to 12 million pipes annually Most of these pipes were inexpensive, produced for a mass-market, in the days when a pipe was part of every man’s equipment. "The workers used to migrate regularly to Saint Claude, France," says Savinelli, "where there was an annual production of more than 30 million pipes, whenever it was slow in Varese, or if they thought they could make better money Some came back to Italy with a different kind of ‘know-how’, because the French industry always had a large share of the high-grade market in England, Germany, and the U.S.. After World War II, when demand increased, Italy began to produce cheap pipes again. My father wanted to change the image and capture some of the quality market."

According to Savinelli, northern Italy was dominated by one major pipe factory at the beginning of the 20th century: Fratelli Rossi (Rossi Brothers), of Varese, with 900 workers producing up to 12 million pipes annually Most of these pipes were inexpensive, produced for a mass-market, in the days when a pipe was part of every man’s equipment. "The workers used to migrate regularly to Saint Claude, France," says Savinelli, "where there was an annual production of more than 30 million pipes, whenever it was slow in Varese, or if they thought they could make better money Some came back to Italy with a different kind of ‘know-how’, because the French industry always had a large share of the high-grade market in England, Germany, and the U.S.. After World War II, when demand increased, Italy began to produce cheap pipes again. My father wanted to change the image and capture some of the quality market."

Giancarlo believes that the timing and location were right, with plenty of briar available in Italy, as well as good labor, and a rebounding national economy "My father moved the goal-posts between 1945 and 1950, and then began to expand production and build up the factory capacity" he says. "It’s really a very simple concept: quality products and natural finishes. Because my father was able to speak several languages and instinctively understood the need to develop an international image through promotion and marketing, all Italian pipernakers must be thankful to Achille Savinelli for reforming the image of Italian pipes.

II. The Time and the Place – Milan is the capital of Italy’s industrial north; high fashion, global finance, heavy industry, vanguard architecture and design, and colossal smog dominate.

II. The Time and the Place – Milan is the capital of Italy’s industrial north; high fashion, global finance, heavy industry, vanguard architecture and design, and colossal smog dominate.

In the midst of the sprawling city, in the old cobblestoned center of narrow streets and trolley cars, is the jewel-box shop that the first Achille Savinelli (b. 1855) opened in 1876. Located near the great Renaissance church II Duomo and the La Scala Opera House, Savinelli is a landmark, a sanctified stop on a pipe pilgrimage.

Along with the Duomo and La Scala, and a few other landmarks, Savinelli makes Milan worth a visit. For it is here that the admirer of the classic and modem pipe so esteemed worldwide can see what made the name so famous. This elegant store carries mostly its own product; Savinelli’s 123-year-old shop is to the Italian pipe what Dunhill’s is to its English counterpart.

But there’s little time to linger. "Do you drive Italian style or American style?" asks Roberto Pome, Director of Marketing, another urbane, well dressed Milanese who speaks several languages fluently. We must follow him to the factory, 50 kilometers northwest of Milan, and we are led on a 100 mph chase up the Autostrada to Gavirate. This small town is central to Italy’s pipernaking traditions, for it was near here that Fratelli Rossi was located.

At the factory, Roberto, whose father worked with Savinelli before him, introduces us to Marco Fumei da Corta, director of production, an articulate veteran of the pipe manufacturing trade. According to Marco, Savinelli produces about 150,000 pipes per year that carry the Savinelli stamp, and more under contract for other companies. About 30,000 are for the U.S. market.

At the factory, Roberto, whose father worked with Savinelli before him, introduces us to Marco Fumei da Corta, director of production, an articulate veteran of the pipe manufacturing trade. According to Marco, Savinelli produces about 150,000 pipes per year that carry the Savinelli stamp, and more under contract for other companies. About 30,000 are for the U.S. market.

We are shown the entire production process, and we notice a few differences from other factories. Of the three stages of cutting the bowls from briar blocks, two are machined and the last is hand-held. All the unique shapes marked "handmade" are completely shaped on an abrasive wheel. Of the entire production, only one in 2,000 is deemed good enough for the "Jubilee" series. As they turn only top-grade "XX" blocks and plateau, mostly from Sardinia and Tuscany, the reject rate is low. With Savinelli, shape and finish choice for the consumer is legion: 72 standard shapes multiplied by all the finishes offer more than 3,000 possibilities.

One finish that only the "inner circle" of Savinelli can observe being made is the "Sea Coral – Capri," a rusticated and oil-treated limited edition presently available in only one shape, a long, narrow-stemmed, high-bowled billiard with a silver band and hand-cut ebonite mouthpiece. This classic is a commemorative to Giancarlo’s father Achille, who favored the shape and finish.

One finish that only the "inner circle" of Savinelli can observe being made is the "Sea Coral – Capri," a rusticated and oil-treated limited edition presently available in only one shape, a long, narrow-stemmed, high-bowled billiard with a silver band and hand-cut ebonite mouthpiece. This classic is a commemorative to Giancarlo’s father Achille, who favored the shape and finish.

When asked about the "schools," Marco reduces the answer with a production chief’s efficiency: "There are only artisan hand-mades and factory-produced pipes. But then, when a factory like ours produces handmades in the same manner as a small artisan workshop, how do you classify them?" he asks with a sly smile. "After all, many of the fancy shapes that look handmade can be produced on a machine with the right die… and most are! To cut a pipe all by hand is actually efficient, however slow, because it allows the pipernaker to follow the grain and feel the wood. There’s less waste."

Giancarlo appears at the factory, this time in jeans and leather jacket, having ridden his motorcycle up from Rome. Tuning in to the discussion, he adds with a wicked grin, "Ask some of the artisan shops to show you the fraizing machines they keep hidden in a backroom. Do you think that anyone who publishes a shape chart can produce hundreds of the same pipe individually, by hand, with any consistency? Why bother?"

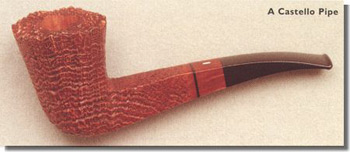

III. Artisan Classicists – In Cantu, a short drive away towards Lake Como, the Castello factory is run by Franco Coppo, a silver-haired gent of the same generation as Fausto Fincato, with the same noblesse oblige demeanor [PipeSMOKE, Winter 98/99]. Coppo married founder Carlo Scotti’s daughter and eventually assumed directorship of the factory. In a rectangular building in the middle of an otherwise unremarkable town, Castello employs only six craftsmen, each of whom makes, or can make, entire pipes. There’s little division of labor. This is intentional, Franco says, because each pipe is the work of one man working for the collective Castello idea: endless renewal with the best possible materials and skill. "When six craftsmen hand-make 36 pipes of the same shape individually, some variations are better than others," says Cop. "If we think one is more interesting than the others, we don’t sell it, but retain it as a model for the future. So we re-invent ourselves daily. "Carlo Scotti started the upper-level artisan pipe when he began in 1947," he continues, "although he was actually making some large ‘freehands’ before World War 11, which he sold to a shop in Switzerland. Because these were large and unusual, everyone called them ‘mad’."

III. Artisan Classicists – In Cantu, a short drive away towards Lake Como, the Castello factory is run by Franco Coppo, a silver-haired gent of the same generation as Fausto Fincato, with the same noblesse oblige demeanor [PipeSMOKE, Winter 98/99]. Coppo married founder Carlo Scotti’s daughter and eventually assumed directorship of the factory. In a rectangular building in the middle of an otherwise unremarkable town, Castello employs only six craftsmen, each of whom makes, or can make, entire pipes. There’s little division of labor. This is intentional, Franco says, because each pipe is the work of one man working for the collective Castello idea: endless renewal with the best possible materials and skill. "When six craftsmen hand-make 36 pipes of the same shape individually, some variations are better than others," says Cop. "If we think one is more interesting than the others, we don’t sell it, but retain it as a model for the future. So we re-invent ourselves daily. "Carlo Scotti started the upper-level artisan pipe when he began in 1947," he continues, "although he was actually making some large ‘freehands’ before World War 11, which he sold to a shop in Switzerland. Because these were large and unusual, everyone called them ‘mad’."

Scotti spent the war in Switzerland and, after returning to Italy, started developing the Castello look: large freehands with elongated bowls, but not ‘freeform’ or ‘organic.’ His variations on classical shapes tend to be medium-size, not gigantic, and he has popularized a spiral cutting that continues from bowl through shank and sometimes stem, long associated with the Castello. He also became known in the U.S. for the "Sea Rock" finish, a heavily rusticated bark-like surface similar to the Savinelli "Sea Coral." Scotti liked the possibilities of acrylic, and introduced that material for mouthpieces back in 1950.

Another aspect of Castello "culture" is the belief that briar blocks, after preliminary curing, should be stored at room temperature, not in an unheated warehouse. All of the briar to be used for the next eight or nine years is stored in piles within the factory, occupying about a quarter of the floor space in the one large production room. This too was Carlo Scotti’s belief, "so it becomes like our daily life: the dark, the light, the winter, the summer. It becomes something we can live with when it is a pipe," he says.

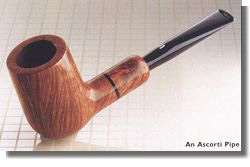

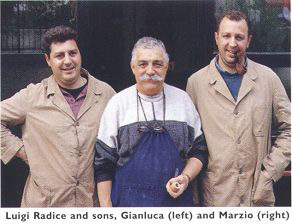

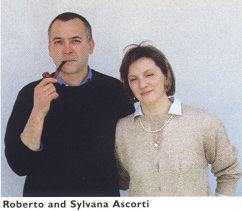

Ascorti and Radice are the other two master pipernakers in the area, both from the neighboring town of Cucciago, both offshoots of Castello. Their common history is straightforward on the surface. Luigi Radice and Pepino Ascorti (father of the present owner, Roberto) worked for Castello in the late ’50s and ’60s, then broke away to form Caminetto in 1969. For 10 years they worked together, then formed separate companies. Ascorti retained the Carninetto brand name, and Radice went out on his own. Today Radice and Ascorti are comparable in quality and technique, although they have evolved in different directions. Caminetto, now made in the Ascorti factory, is a secondary line, not at the level of Ascorti’s best.

Ascorti and Radice are the other two master pipernakers in the area, both from the neighboring town of Cucciago, both offshoots of Castello. Their common history is straightforward on the surface. Luigi Radice and Pepino Ascorti (father of the present owner, Roberto) worked for Castello in the late ’50s and ’60s, then broke away to form Caminetto in 1969. For 10 years they worked together, then formed separate companies. Ascorti retained the Carninetto brand name, and Radice went out on his own. Today Radice and Ascorti are comparable in quality and technique, although they have evolved in different directions. Caminetto, now made in the Ascorti factory, is a secondary line, not at the level of Ascorti’s best.

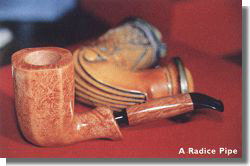

Luigi Radice is a bear of a man, with a huge mustache and a hearty manner. He works in a small workshop with his two sons, Marzio and Gianluca, and produces pipes that continue the Castello mode with some individual Radice characteristics. Ninety percent of his 1,800-per-year production are for export, with about 1,200 coming to the U.S. Most are modifications of classic shapes; some with the spiral shank, others with a bamboo insert replacing the briar shank, still others with elaborate rings and bands made of silver, horn, and rare woods. Radice’s mastery of the silver band is legendary His rustication has what he calls a "soft" look. When it comes to the one-offs and specials, Radice is an unparalleled carver. It is priceless master craftsmanship worthy of a collection of the world’s greatest pipes.

Roberto Ascorti’s factory resembles its owner: spare and modem. Stylish and aware of trends, the 40-ish Roberto and his wife Sylvana’s best work seems to be on the cutting edge of Italian pipe design. They have a hyper-critical eye for detail, confidence in their judgment, and a strong distaste for clichés and stereotypes.

Ascorti makes all the classical shapes to suit his own sense of proportion. He will take a completed pipe that he doesn’t care for, sand off the finish, modify the form slightly, even change the costly hand-cut 7% mouthpiece because it doesn’t satisfy his eye. If he still doesn’t like the result, the pipe is rejected.

We watch him make a couple of pipes. "I cut on a bandsaw to test the block, to leave the ‘heart’ in the center. If I don’t see anything there, it doesn’t become an Ascorti," he says. He moistens one of the cut blocks and shows us. No pencil layout this time: "I’ll find the form as I work. This one will have excellent grain but it will run on a slant." He turns the block around. "Short bowl, but wide," he opines, "and Is enough for a long shank. Here’s the way…."

The rough cut emerges: a sort of squat ‘apple’ (actually, it’s more like a tangerine), with a long, wide round stem, and the grain starts at the middle of the shank bottom and radiates forward in a ‘V’ towards the bowl, as well as back towards the mouthpiece. The leading edge of the bowl is birdseye, perfectly balanced in the center between the slanted straight grain that seems to reach around the swirls like fingers.

"Now what shape is next?" he asks. "How about ‘Dublin’, eh?" Another block is cut, and penciled because he wants a specific shape. He doesn’t like what the first cuts tell him, so he repeats the process and finds a block he likes. "Perfecto, " Ascorti says after the preliminary cutting and sanding. Cesare Vigano, a master pipernaker who worked with Roberto’s father, takes away the pipe for finishing. A few hours later, Roberto shows us the Dublin. With it is the ‘tangerine’ he made earlier. "Now you can smoke Ascorti," he says proudly, "at least while you’re here!"

Besides the pleasure of watching a master pipernaker at work and seeing his aesthetic sensibility functioning in tandem with his consummate technical skill, what we observed in watching Ascorti is greatness – one of the best ever, easily comparable to any of the great pipe carvers of the world. There are few baroque elements in his work; rather, a whimsical use of superior industrial forms, reevaluated by perhaps the best hands in the business.

IV. Synthesis in a Factory – Pipemaking has not changed in 50 years; the market has," says Luciano Buzzi, the proprietor o Brebbia. He has driven to the factory in a racing-green 1950 MG convertible that he has painstakingly restored to original mint condition. Like his car and his international designer clothing, Luciano and his Brebbia pipes have flair.

Luciano is an architect by profession who took over the business started by his father and Achille Savinelli in 1947. Enea Buzzi became independent in 1953 and subsequently adopted the Brebbia name – actually, the name of the town, near Lake Maggiore, a few miles west of the Savinelli factory in Gavirate. Enea recently turned the management over to Luciano, who is streamlining the business. Built over and around a hydroelectric station on a river that supplies all the plants’ electrical needs, the factory, with a staff of 14, turns out about 35,000 pipes a year.

Luciano is an architect by profession who took over the business started by his father and Achille Savinelli in 1947. Enea Buzzi became independent in 1953 and subsequently adopted the Brebbia name – actually, the name of the town, near Lake Maggiore, a few miles west of the Savinelli factory in Gavirate. Enea recently turned the management over to Luciano, who is streamlining the business. Built over and around a hydroelectric station on a river that supplies all the plants’ electrical needs, the factory, with a staff of 14, turns out about 35,000 pipes a year.

Brebbia uses hand-operated fraizing machines to cut the basic shapes; the rest is done by hand. "It’s very difficult to cut the basic classical shapes by hand, because all the little adjustments for grain and shape produces a non-classical shape," Luciano says. "I admire a lot of the artisan work, but I can produce beautiful pipes Much more efficiently. The seconds become an alternative brand ["Cellini"] and the ‘fallings’ are sold as ‘no-name’ [private label] pipes. But they all smoke just as well, because the briar is the same quality to start with."

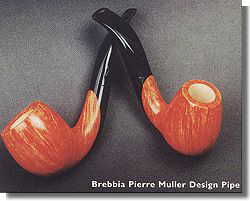

According to Luciano, his factory makes a synthesis between the industrial and the artisan pipe. Generally a bit larger, longer, and fuller-bodied than his main competitor’s (Savinelli) pipes in the classical shapes, even the unique designs are different; more of a synthesis of sleek Danish design with Italian vitality. There is a preference for lighter colored finishes, and for elaboration with silver bands and other ornamental materials, verging on the baroque/ rococo, but not quite there. "We give the same attention to detail as a small workshop, but produce enough to keep all these people employed, and run a profitable business too," Luciano says. "Sure, we make a few completely handmade pipes from time to time, but that’s for the collectors. Design, for an architect, is something that can be reproduced. Like architecture, pipernaking is a useful art, and if you get too lost in the finer points of handcraft, the building or the pipe doesn’t get built, or costs a fortune. I don’t believe in that."

According to Luciano, his factory makes a synthesis between the industrial and the artisan pipe. Generally a bit larger, longer, and fuller-bodied than his main competitor’s (Savinelli) pipes in the classical shapes, even the unique designs are different; more of a synthesis of sleek Danish design with Italian vitality. There is a preference for lighter colored finishes, and for elaboration with silver bands and other ornamental materials, verging on the baroque/ rococo, but not quite there. "We give the same attention to detail as a small workshop, but produce enough to keep all these people employed, and run a profitable business too," Luciano says. "Sure, we make a few completely handmade pipes from time to time, but that’s for the collectors. Design, for an architect, is something that can be reproduced. Like architecture, pipernaking is a useful art, and if you get too lost in the finer points of handcraft, the building or the pipe doesn’t get built, or costs a fortune. I don’t believe in that."

Recently, Luciano’s awareness of international design led him to start a new line of designer pipes. He invited Rainer Barbi of Germany and Pierre Muller of Switzerland, both renowned craftsmen in the pipe world, to send him replicable designs for pipes. Each contributed a model characteristic of his own style: Muller, a large, classic bent Franco/Swiss billiard with an acrylic crossover from stem to shank; and Barbi, a conical, Nordic quarter bent with a bullcap bowl top and a military style mouthpiece. Brebbia’s program with guest designers will grow, says Luciano, so that he can bring modern design to the pipesmoking market. "Today’s pipe business is to please collectors of good design, and I intend to make the best works available at reasonable prices," he comments.

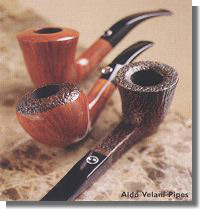

V. Beyond the Pale – There are a few brands of Italian pipes on the U.S. market that are hardly known in Italy, as they are made in factories dedicated to the export trade. Aldo Velani is a line imported from Italy by Lane Limited, Dunhill’s distributor. Made mostly in Livorno by Cesare Barontini, one of the best known private-label manufacturers, Aldo Velani pipes are classic shapes with an Italian ‘twist,’ according to Frank Blews, a spokesman for Lane. "Billiards with more ‘ball,’ bulldogs with more ‘jaw,"’ is the way he characterizes the line. A medium to large pipe specifically developed for American tastes, the finishes use the names of Italian wines – Soave, Novello, Barolo, Refosco – to suggest their colors, and there is a lot of ornamental work.

V. Beyond the Pale – There are a few brands of Italian pipes on the U.S. market that are hardly known in Italy, as they are made in factories dedicated to the export trade. Aldo Velani is a line imported from Italy by Lane Limited, Dunhill’s distributor. Made mostly in Livorno by Cesare Barontini, one of the best known private-label manufacturers, Aldo Velani pipes are classic shapes with an Italian ‘twist,’ according to Frank Blews, a spokesman for Lane. "Billiards with more ‘ball,’ bulldogs with more ‘jaw,"’ is the way he characterizes the line. A medium to large pipe specifically developed for American tastes, the finishes use the names of Italian wines – Soave, Novello, Barolo, Refosco – to suggest their colors, and there is a lot of ornamental work.

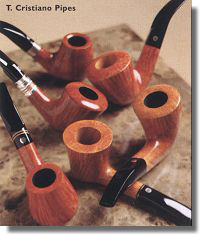

Another good Italian pipe is, the T. Cristiano, created by Thomas Cristiano, an Italian-born American who has spent his entire working life in the pipe manufacturing trade. Associated with various companies over the years, including almost a decade as importer and distributor for Mastro de Paja, Thomas established his own company, Cristom, in 1982, and has developed a very strong market in the past few years for three lines of pipes: Calabrese Series, Cristiano Series, and the T. Cristiano Signature Series. Most of these are made for him by Barontini and represent an entire range of Italian design, from the baroque handmade to the sleek machined designs that characterize the Milan ambiente.

Developed in mostly larger sizes with the traditional American pipesmoker in mind, Tom is now shifting his focus for the top-of-the-line T. Cristiano Signature Series to slightly smaller hand-cut pipes with light finishes and finely wrought silver fittings. The TCSS has managed to join the spirit of the artisan-made pipe from Pesaro with the manufacturing capability Of a large factory, to create a series which has the artisan workshop look and feel, but priced to suit the average buyer. The pipe belongs to no "school," but still boasts a good Italian education.

Developed in mostly larger sizes with the traditional American pipesmoker in mind, Tom is now shifting his focus for the top-of-the-line T. Cristiano Signature Series to slightly smaller hand-cut pipes with light finishes and finely wrought silver fittings. The TCSS has managed to join the spirit of the artisan-made pipe from Pesaro with the manufacturing capability Of a large factory, to create a series which has the artisan workshop look and feel, but priced to suit the average buyer. The pipe belongs to no "school," but still boasts a good Italian education.

VI. Ave Atque Vale ("Hail and Farewell!") – We have tried in this two-part article to create a feel for the Italian pipe, its provenance, directions, schools, and influences. We’ve received a lot of mail calling the article "seminal" or "definitive," but that wasn’t our purpose. All we tried to do in the limited time and space available was to look at the key elements in a very complex phenomenon, a national tendency in the pipemaking "culture" of a country. Those readers who expected a laundry list of brands, including their own favorite, may be disillusioned What we have attempted is to set up parameters for looking, judging, and thinking about Italian pipes. Best of all, for smoking them with the pleasure that only a fine pipe can bring to tobacco.

PipeSMOKE – Spring 99

When it comes to style and beauty of design the Italians have few peers. And since Luciano Buzzi drives a MGTC I’ll cherish my Brebbia pipes even more.

When I smoke I mostly pay attention to the tobacco and how the pipe is smoking, which reduces to a concentration on optimal draw and absence of gurgle; said differently if it has two holes and the above, I’m good. But I do enjoy enjoying the pipe itself, but if there’s nothing there that piques my interest, I return my attention back to the smoke.

I like many styles of pipes, among them the Italian.