Alan Schwartz

From the moment you walk in to the A&C Petersen factory, you know these guys don’t just make tobacco, they live it. On the horizontal support beams that cross the room are literally hundreds, maybe thousands, of tobacco tins collected over the years by the Petersen brothers, Hans and Jens -including many older American specimens that tobacco museums and collectors would envy. All around the office are other artifacts – antique machines for pressing, cutting, and mixing tobacco are standing accents, along with cigar store Indians, old smokeshop signs, and display posters.

From the moment you walk in to the A&C Petersen factory, you know these guys don’t just make tobacco, they live it. On the horizontal support beams that cross the room are literally hundreds, maybe thousands, of tobacco tins collected over the years by the Petersen brothers, Hans and Jens -including many older American specimens that tobacco museums and collectors would envy. All around the office are other artifacts – antique machines for pressing, cutting, and mixing tobacco are standing accents, along with cigar store Indians, old smokeshop signs, and display posters.

The conference room is set up like a smokeshop, with counter-height glass cases containing pipes and tobaccos, old and new cigarette packs that have visual or historical interest, and humidor sections full of cigars. The walls are covered with tobacco posters and prints and woodcuts from old books on tobacco plantations in the “New World.” In short, the room is a microcosm of the tobacco universe of the past and present.

The display is neither just for show nor for the personal pleasure the Petersen brothers feel by surrounding themselves with the visible history of their craft. “If you don’t know where you come from, then you don’t know where you’re going,” Hans says. “That’s part of the reason for accumulating this stuff, in addition to the plain fun of collecting. But there’s also a practical side. I get a lot of ideas about packaging, about brand names, even about new blends from all this. And some of the older machines we come across help us to design new ones.”

The display is neither just for show nor for the personal pleasure the Petersen brothers feel by surrounding themselves with the visible history of their craft. “If you don’t know where you come from, then you don’t know where you’re going,” Hans says. “That’s part of the reason for accumulating this stuff, in addition to the plain fun of collecting. But there’s also a practical side. I get a lot of ideas about packaging, about brand names, even about new blends from all this. And some of the older machines we come across help us to design new ones.”

The Petersen brothers are not only collectors of tobacco history-they are part of it. Their great grandfather started a tobacco, cigar, and snuff factory in Horsens, Denmark, in 1865; his sons took over around the turn of the century, and then one of the grandsons, the father of Hans and Jens, started his own factory in 1932. In the 1970’s, having done their apprenticeships in England, Germany, and the U.S., Hans and Jens began to operate the A&C (Alfred and Christian-their respective middle names) Petersen factory on their own, still in Horsens, in the “Midwest” of Denmark. Like most educated Danes, they speak fluent English and German, the languages spoken, not so coincidentally, in their largest markets.

Whether it is a classic natural or lightly aromatic Danish blend, a deeply flavored black Cavendish that is favored by American and German smokers, a full-bodied traditional English mixture with Turkish and latakia tobaccos flavoring the Virginia base, or the latest flavor innovation in the global market, the Petersen’s make it, either for their own brands or for someone else’s. For variety and sheer tobacco making experience, A&C Petersen is tops.

Our journey begins in the warehouse, accompanied by both Hans and Jens. While both Petersen’s are extremely knowledgeable, the labor is divided such that Jens is the tobacco man and Hans does the marketing and administration. Jens’ responsibilities include purchasing all the leaf, overseeing the blending, and running the testing and development laboratory. Hans develops ideas, globetrots to service accounts, and supervises the retail and franchise operations of the Paul Olsen “My Own Blend” smokeshops.

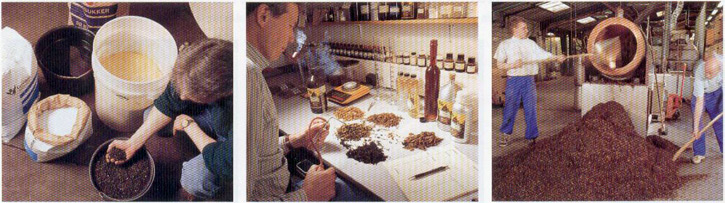

Jens cuts open a quarter-ton box to show some Virginia leaf grown in Zimbabwe. “Excelllent tobacco,” he says, “but look at this, from the Piedmont district of North Carolina.” He takes a leaf from an opened bale piled on a skid. The American leaf is a richer, almost lemony, yellow color. "Much higher nicotine content in this, and really fine tobacco, but too strong to use by itself, so we blend it with Rhodesian leaf (like most tobacco men, Petersen uses the old name for Zimbabwe), which is high in natural sugar."

How does Jens know about the specific nicotine and sugar content in the tobacco? Is every bale checked? "We spot-check in my laboratory, and you can tell by the look and feel of the bale," explains Jens.

"We depend on our brokers," Hans adds, "and we’ve been doing business with some of them since my grandfather’s day. They know what we buy and send us only what falls within the specifications we want."

"Anyway," Jens adds, "the chemistry varies slightly from crop to crop, as with any natural product, depending on the annual rain fall, days of sunshine and so on. The art of the blender is to under stand that and make minor adjustments in the blend proportions to compensate for natures tricks."

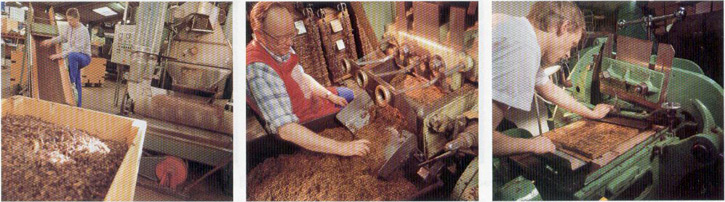

From the warehouse, where the leaf is stored at its shipping state of 10 to 12 percent moisture, the tobacco is taken to be steamed and moisturized so that it becomes pliable and workable. Then it is threshed in a large (car-sized) cylinder with pitch fork blades to cut the tobacco and remove the stems. An internal air blower pushes the lighter leaves up and out while the stems fall to the bottom, and are gathered for flattening and use, mostly in cigarette tobacco, which A&C Petersen also makes for the huge European roll-your-own market. "Nothing wrong with stems," Jens says. "Got a lot of taste."

Large hoppers are filled with strip (leaf with the stalk removed) proportioned to make "base blends." Weighed out in 600- or 900-kilo loads, depending on inventory needs, the tobacco is steamed and then tumbled in a cleansing drum the size of a construction-site cement mixer to remove impurities such as sand and stalk residues, then "cased" (sprayed with water, or with a mixture of water and various flavoring agents) in another huge drum. A&C Petersen has twelve base blends, the building blocks of all their other tobacco products. Each one is treated on its own, cased, stored, and aged according to recipe.

The basic twelve, in a variety of combinations and proportions, allow for a huge number of possibilities, especially when condiment tobaccos such as latakia and perique are used in small proportions, or a different "top-dressing" (a compatible flavor using the same elements in the base blends, which can be neutral or very intense) is sprayed on the finished product to meld or "marry" the different ingredients.

"Casing is a process [that is] often misunderstood," Jens explains. "All tobacco is cased. Water is a casing, as is a water-based mixture of flavorings, from the most neutral sugars to the most elaborate confections. For the natural, unflavored tobaccos, such as the traditional English mixtures and classic Virginias, we use only water. For the others we use a range of natural flavorings, from plain, neutral sugars to complex recipes of aromatic essences." The vast range of tastes and aromas available in modern pipe tobaccos, and demanded by today’s pipe smokers, would he impossible with out casing.

Additionally, the Petersen’s proudly point out that they use only natural ingredients for their casings, such as licorice, brown sugar, fruit, and spice essences. Hans leads us to a room the size of a house, filled with cold-storage bins containing big chunks of pure licorice and pressed cakes of brown sugar. Barrels of prune and other extracts and boxes of vanilla beans and cocoa are piled high.

At this point in the process, the tobacco is still in its rough stage. Not yet cut to smokeable proportions, each blend is nonetheless ready to be further processed. From blending boxes as large as an automobile, the tobacco is fed into a machine that cuts it to a size that is smaller, but still not yet ready for pipe stuffing. At this stage some base blends will be stored and allowed to mature for weeks in the bins. Others will be "stoved," or conveyed through an oven, to both speed up and control the fermentation process. Still others may require only a day or two in the bins before they are ready to use. A few of the base blends have been designed to be pressed into "cakes." Poured into an approximately two foot square mold, the loose tobacco is then pressed flat into a cake about two inches thick, then removed and placed in a high, vertical press with twenty or more similar cakes, and kept under intense pressure for days or weeks. Some of the cakes will be "stoved" after pressing, and then go back into storage for two to three months, when they will be cut by a guillotine into slices (like sticks of chewing gum). Thus is made the product known to the pipe smoker as "flake," a type of tobacco that needs to be crumbled or "rubbed out" by the smoker before putting in a pipe. Other cakes will be stored for shorter periods, then tumbled in a "breaker" machine to partially separate the cake (the layers of leaves still adhere from the original pressure) into "ready-rubbed," ready to smoke pieces.

An alternative fate for the base blends at this phase of manufacturing is the making of "twist" or "spun" tobacco. In a process somewhat akin to rolling a cigar that is six feet long, the desired blend is placed by hand in long leaf wrappers and twisted together into a continuous strand, in effect, a rope of tobacco. Here, some of the central leaf stalk that was removed at an earlier stage of manufacture is added back in to serve as a stiffener. When the strand is complete, the pressure placed on the "twist" is intense, not unlike that put on the "cakes" in presses, as described above. A long or short storage period for the tobaccos in the strand, to age arid fully mature, is required, and then the twists are sliced in a guillotine cutter across the grain into individual "coins," each one showing the tobacco in cross-section, with the stem pieces as little round flecks known as "birdseye." This sliced twist tobacco, sometimes called "spun cut" or "curlies," is then spread out Lo dry and then packed in tins ready to smoke, or kept in bins to be used in complex blend recipes that require some "twist" along with the loose and ready-rubbed tobaccos.

At this point, the tobacco is ready for the actual blending into the mixture that the consumers will finally put in their pipes. The Petersen’s walk us to the blending area, where the "mixtures," a term that actually means a blend of blends, are prepared. The equipment here is pre-industrial, mostly shovels and rakes. Bins of tobacco have been weighed out according to the recipe for the mixture being prepared, brought to the spotlessly clean mixing floor on hand trucks, and dumped, in volume order, the largest to the smallest. As this is being done, two or three workers with rakes and shovels turn over the tobacco, rake it across, turn it again and rake it again until the mixture looks even. The tobaccos are still in large pieces, about three to four inches long and an inch or so wide. Included in these mixtures, depending on the recipe, are chunks of the pressed and then ready-rubbed "cake" tobacco, and sometimes sliced "twist" or "curly cut" tobaccos, as well as the straight, unblended condiment tobaccos such as perique or latakia, if required by the recipe. This is the way tobacco has been blended for hundreds of years.

Why is all of this necessary, when huge, modern mixing machines are available? "We can get a better quality control this way, because four to six people are doing this, depending on the size of the batch we are mixing, and someone is bound to spot a problem I if something is wrong," comments Hans.

Now the tobacco goes from the mixing floor into a large cylinder where it is mixed and sprayed with water and small amounts of glycerine, to make it pliable for cutting. Because some formulas call for a mixture of finer and coarser cuts, these will be premixed and cut separately and then remixed afterward, as are "curlies" and bits of "flake" that the master blender wants to keep integral.

After the cutting of the larger leaf tobacco and the remixing of separated elements, the tobacco is dried again from the 25 percent moisture level needed to cut it without damaging the leaf, to the 18 percent level A&C Petersen thinks is the proper humidity content for its tobacco. It is here, in the drying chamber, that the mixture can be "top-dressed" with a light spray of an aromatic essence that either unifies the various tobacco tastes or merely creates the "bouquet" that the smoker sniffs when a pouch or tin of new tobacco is opened.

The next and last stage is "lagering" (storage of the final product) in bins for a minimum of one month at a constant 60-degree temperature, and an ambient humidity of 65 percent. Now the tobacco is ready for packing. Flakes and curly cuts are weighed out and packed by hand, lest the tobacco crumble in the process. Loose mixtures are packed in pouches by machine, or in the traditional round or rectangular 50-gram tins, by a combination of machine and hand work. At the end of our visit to the A&C Petersen tobacco factory, we know we’ve had a thorough education in the art and craft of pipe tobacco-making, from a family with tobacco in its blood. There’s a love of the craft and a passion for the product here, and it’s clear why A&C Peterson is a world-class tobacco operation.

PipeSMOKE Summer 1997

Kevin,

Thank you for pulling this from the archives and sharing with us one of the most comprehensive articles on the start to finish blending process that I’ve ever read. What I wouldn’t give to have been part of that tour. Two things popped out at me while reading this and number one is that the term “casing” has long been misunderstood and number two, and most disturbing, is that we pipe smokers are prone to loading our pipes with “curlies”. I just hope they are not of the “short” variety. A great read!

Great reading! What really struck me, besides the intense work and elaborate processing, was the whole moisture issue. We always seem to be concerned about how tobacco dries out and how to go about remoistening it, and whether it will still be flavorful afterwards. This article demonstrates that the original condition of the bales of tobacco are too dry to feasably work with, thus remoistening is required. Furthermore, it may again be remoistened during the process. This leads me to the conclusión that remoistening tobacco that has dried out, but still remains intact, can readily be done without any significant effect to the product. Granted the aging process may be inhibited should the tobacco be stored at too low a moisture level, but when it comes to remoistening your tin or pouch, should it get a little dry as the days go by, no major negative effect should be expected.

Er, is this an advertisement?

I have never sampled any of his company’s products I am sure they are very good, but this article seems a bit of a lovefest.

@thehappypiper – Did you notice at the top of the page, and at the bottom of the page that this is a “reprint” from 1997? A&C Petersen was best known as one of the producers of Escudo Navy De Luxe since it has been a very popular pipe tobacco throughout its nearly 100-year history. A&C made Escudo from 1997 to 2000 when they were acquired by Orlik, which is now STG (Scandinavian Tobacco Group).

Definitely a great read, thanks Kevin for digging this one up.

A great read about a great tobacco firm.

What a fantastic, detailed look I’ve gotten from this article.

I had always assumed that this firm went out of business, having given up the rights to Escudo. How then did this happen, given that we all seem to love it, buy it, smoke it and age it? I have 70 tins and wish the number were twice that, and I would were it not twice as expensive as the bulks that I smoke, and love.

There are many alternatives, some less expensive, such as Comoys Cask #7, which smokingpipes sells for $12.37, which I will try. But for a vivid spun cut VA/Perique, dollar for dollar, Escudo has no real challenger.