By G. L. Pease

In some ways, what follows is sort of a continuation of my last column, The Fickle Nature of First Impressions, so if you haven’t read it, it might be a good idea to give it a look. Basically, I discussed how our perceptions can be somewhat capricious when exposed to novel things, especially within the context of something as seemingly simple, yet deceptively complex as pipe smoking. There are many variables – the pipe, the tobacco, the smoker’s mood, the weather, what we’ve eaten, to name just a few – converging on that last puff from a great smoke, and a change to any one of these things can affect our experience in surprising and sometimes surprisingly significant ways. Amongst those myriad variables are all the things related to discernment, and that’s what we’re going to look at here.

In some ways, what follows is sort of a continuation of my last column, The Fickle Nature of First Impressions, so if you haven’t read it, it might be a good idea to give it a look. Basically, I discussed how our perceptions can be somewhat capricious when exposed to novel things, especially within the context of something as seemingly simple, yet deceptively complex as pipe smoking. There are many variables – the pipe, the tobacco, the smoker’s mood, the weather, what we’ve eaten, to name just a few – converging on that last puff from a great smoke, and a change to any one of these things can affect our experience in surprising and sometimes surprisingly significant ways. Amongst those myriad variables are all the things related to discernment, and that’s what we’re going to look at here.

What’s the difference between the expert taster and the neophyte? Experience and focus, mostly. We all have roughly similar hardware, and our innate abilities are close enough for jazz, yet how we perceive things can be markedly different. (Of course, some people are born with a greater than average ability to taste or to smell, but unless those native abilities are cultivated, even the super-taster has no real edge over us.)

Our ability to discern flavors and aromas is largely based on training, whether consciously or unconsciously. Much of this training happens mostly automatically. We learn to recognize bananas as different from hot dogs fairly early in life, and as we grow up, the list of what we can identify grows without much attention being paid to it.

The average adult is capable of recognizing over 1000 different flavors – a pretty impressive number.

If you sat down and started listing all the tastes you can think of off the top of your head, you’d likely run out long before approaching 1000, but the rest of them would still be there, waiting in shadowy doorways to pop out when you least expect it.

What’s different about the experts is that they’ve learned to focus more acutely on what they’re tasting or smelling, and to make associations that aren’t necessarily natural to the rest of us, and to build their vocabulary to be closer to those 1000 flavors. When we taste a grape, there’s no doubt that we’re tasting a grape, but if the same flavors were present in a steak or a cocktail, the connection might not be made so easily. But, we can all learn to do what the experts do, and, I believe that by doing so, we can derive greater enjoyment from our pipes and tobaccos.

Each of us has our own unique sensory library that we hook into when we taste or smell something. Of course, there is much overlap, at least within a given culture, but it’s the stuff outside of the intersection where the interest lies. And, pipe smokers do have their own culture, in this respect. Mention leather and smoke, and immediately, Latakia will likely come to the mind of a pipe smoker, while memories of horseback rides on the beach and driftwood fires might be conjured by someone unaccustomed to our peculiarities. That’s what I mean by sensory library. It’s not the words we use, but the memories of the experiences themselves. (From this point on, by the way, I’ll use the words taste and smell more or less interchangeably, so where you see one, you can just as easily plug in the other.) Here’s an example to illustrate this point.

I was tasting a couple wines with some friends the other night, and we were having our usual good time puffing smoke over what we thought about them. In one of the wines, I picked up on something a little unusual, and with my typical lack of concern for the linguistic conventions laid down by some of the more humorless wine people* I’ve been acquainted with, I described what I smelled as "old bicycle inner – tube." It fit. (Robert Mondavi, one of my early mentors in the art of wine tasting, would have been pleased.)

I was tasting a couple wines with some friends the other night, and we were having our usual good time puffing smoke over what we thought about them. In one of the wines, I picked up on something a little unusual, and with my typical lack of concern for the linguistic conventions laid down by some of the more humorless wine people* I’ve been acquainted with, I described what I smelled as "old bicycle inner – tube." It fit. (Robert Mondavi, one of my early mentors in the art of wine tasting, would have been pleased.)

One of my friends didn’t quite get what I was on about at first, but the next time he poked his beak into the glass, the light went on. As an avid bicyclist, this is a smell I’m sometimes more intimately familiar with than I’d like to be, while for him, the same smell is tangled with long dormant childhood memories. What was an easy recall event for me required some prompting for him. But, when he got it, he couldn’t let go. He now noticed the aroma effortlessly. The smell had always been there, but it was lurking just beneath the threshold of his perception, not because the apparatus didn’t trigger, but because that trigger didn’t hit the long – dormant neurons that associated it with bicycle inner-tubes. Once that memory was refreshed, though, his recall was instant. (Fortunately, by the way, the smell dissipated as whatever was causing it slowly volatilized from our swirling glasses.)

Tasting tobacco is a lot like this, if slightly complicated by the involvement of the pipe, and its ghosts, and their interactions with the tobacco we’re smoking, and all the other stuff I talked about last month. Often, once a flavor or aroma in a tobacco is pointed out to us, perhaps through a review or the label’s description, it becomes obvious, whereas before that revelation, the same taste may have remained partially or even completely submerged. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been smoking something while reading a head-scratcher review of the same or a similar tobacco, only to have what the reviewer mentions suddenly appear from the mists. I’d bet something similar has happened to most of us. Once we pick that thing out and stick a label on it, we’ll probably never miss it again, even when it appears in other blends.

There’s been no sudden change to the apparatus. We’re using the same nose and tongue we’ve always used before these turning points. The difference is in the brain. New connections have been made, or old ones reinforced, and once these pathways are strongly established, next time, the recall will be effortless and instantaneous. Think of black pepper. Don’t sneeze. It’s kind of like a magic trick. Once you know the magician’s secret, the trick never looks quite the same again.

In fact, all sensory experience is like that, all little brain tricks, like a giant "Where’s Waldo" puzzle. Once you find him in the jumbled chaos, he almost magically jumps out of the page every time you look at it. Or, like the hairy wart on great – aunt Hilde’s nose that you can’t stop staring at once you notice it for the first time. Don’t think of a purple giraffe. Notice how quickly images can be brought up where none may have existed before.

Since I’m in the position of tasting tobaccos at all stages of their evolution, I am consciously aware of things in their smoke that the average pipe smoker may not be. So, sure, I probably pick up things that most won’t, at least at first, simply because they’re right on the page in front of me. A friend of mine, a professional opera singer, hears things in voices that I don’t – until he points them out to me. But, as with anything else, everyone can learn some of the tricks, and so sharpen the acuity of their tasting.

Since I’m in the position of tasting tobaccos at all stages of their evolution, I am consciously aware of things in their smoke that the average pipe smoker may not be. So, sure, I probably pick up things that most won’t, at least at first, simply because they’re right on the page in front of me. A friend of mine, a professional opera singer, hears things in voices that I don’t – until he points them out to me. But, as with anything else, everyone can learn some of the tricks, and so sharpen the acuity of their tasting.

The most important part of developing discernment is to focus attention on what’s being tasted, and try to fit apt descriptions for the various flavors, doing so as specifically as possible. Don’t settle for "citrus" when "pith of ripe grapefruit," or "oil from lemon peel" is more accurate. Look beyond the clichéd terms in use every day, and find those things from your own experience to describe what you’re tasting. In very little time, the experience will be noticeably enhanced by this procedure. (Though, every once in a while, Latakia will produce a flavor that I, for years, have been trying to pin down. It’s as familiar to me as the smell of a rose, but I cannot for the life of me name it, and it drives me crazy. It becomes like a song in my head that will not leave. One of these days, I’ll figure it out.)

I’m not suggesting that anyone would want to always smoke this way. There are times, as I mentioned last month, when just sitting down to a good puff is reward enough. We don’t always have to engage critically, when sometimes simple relaxation is sufficient. But, overall, at least for me, the experience of pipe smoking has been greatly enhanced the more deeply I’ve engaged with it, so a little mental effort along these lines once in a while seems to be grey matter well occupied.

Try it. Take some notes next time you light a bowl. Describe the flavors, the way the smoke feels in your mouth, the aromas in the tin, in the pipe, in the smoke. Refine your descriptions throughout the bowl, getting more detailed as you go. In no time, you’ll be describing things just like the experts.

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. |

“What’s the difference between the expert taster and the neophyte? Experience and focus, mostly.”

… and memory I think Greg; hinted at above but I really do think, as in wine tasting, the ability to recall a taste matters more (or at least as much) as the simple ability to taste. Again, as in wine, the only way to develop taste memory, if it isn’t there naturally, is by side by side tasting.

Some smokes memories last for years but, I would suggest by external association – at the bus stop on the way home from college, a first date, walking down the drive at Hampton Court – otherwise it’s a deliberate cultivation of comparisons and a trip to log them in to Hannibal’s memory palace.

Good point, Jim, and quite right!

The connection between memory and olfaction is very strong. I still recall my first love when I smell the synthetic green apple scent that’s used in some shampoos.

But, memories aren’t always reliable, and it turns out that every time we recall something, the process of ‘re-remembering’ it alters the memory sufficiently that, over time, it can be quite different from what it was originally. Of course, producers of things (like tobaccos) use this to advantage. Remember how dramatically a blend like Balkan Sobranie changed, albeit in subtle increments, over the years, but those whose taste memories were routinely ‘adjusted’ by continual smoking noticed little of these changes. Only those who smoked it, stopped, and then years later, returned to it were likely to scratch their heads about the difference found in the leaf in those later tins.

I think the whole issue of recall and comparative tasting is a great subject, if a complicated one. Maybe a future column.

-glp

It’s truly amazing how the 4 or 5 basic taste bud sensitivities: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and, some assert “umami” can combine to form the 1,000 flavors you mentioned. Greg, I think you’re getting right to the heart of the psychological aspects of the epicure’s art.

I’m glad to see someone else acknowledge that a big part of taste discernment is the development of a descriptive vocabulary, and the feedback loop which that facilitates with memory.

So much to discuss about this article, but I won’t hog the bandwidth here. Thanks for articulating the ineffable!

Enjoyed the article! Greg makes a viable point of once something is bought to your attention it takes command. One thing he didn’t mention was the pipe that is smoked. I can understand why, as identical pipes can smoke differently much as the same brand “identical” musical instrumentals can play differently for the player and sound differently for player & listener. Great article. The illucivenous of pipe smoking is like the onion that has many layers. Much like

improvising in jazz..the more you find out the more you realize what you don’t know. The never-ending book. Thanks Greg!

Ah, but I did mention the pipe in the previous article! Glad you enjoyed it, Funn.

And, Cortezattic, bring on the disucssion. It’s certainly welcome.

-glp

I have always hd trouble identifying, putting words to some tobacco blends I taste. Straight VA for instance. Comforting aroma for sure. They call it sweet tasting, haylike, etc. I never would in a million years come up with grassy, haylike taste. I occassionaly as a kid wound up with grass in my mouth playing a rolling around and such but never saw it as sweet. It was usually more bitter/acrid to me. And haylike? Can’t say that I’ve consumed much hay either, if at all. In the case of VA tobacs I have learned about breath smoking and can find comfort in what the fuss about straight VA’s is. I’m smoking MacBaren’s VA #1 as I write this and MB is known as hot. I’ve had it as a torch and as a pleasant experience. Nuff on slipping into a review,forgive me. If VA’s are grassy and haylike and that’s what it’s called that I’m tasting, so be it. I never knew what that ‘smell’ was in the tobacco shop at the mall was when

I was in my very early teens but I knew I liked it. Few friends said it smelled to them like old socks burning but it intrigued me. Starting pipes and thru Dad’s ionfluence tobacs at 16, I found that it was an english blend called Balkan Sobranie. You know I bought some. The older gentleman behind the counter told me that the thick, heady smell was him smoking Balkan Sobranie. Yup, thick heady, almost stinks but I like it. If leathery, woodsy is what that thick, heady aroma is then so be it. If it really is socks, guess what, I still like it, English blends are the grail of pipe smoking to me whatever the description.

Is there any particular way that I can enhance my vocabulary or whatever it is to more accurately decsribe what I experience while smoking my pipe and tobaccos? Sometimes your tin descriptions defy tastes as some are described as symphonic revolutions and not a word of tobaccos. However your descriptions do justly fit and gets me wanting to purchase different blends. Cumberland is wonderful and tickles my fancy and Barbary Coast takes me back to my drinking days, in an affectionate manner. It was me that messed up drinking. Thsoe are just wo that stand out to me currently. thank you and hope to see some suggestions on my question.

Descriptions are hard, especially for the guy writing the label. (That would be me.) Once in a while, I’ll talk about the various tastes that I get, but someone else might find something completely different. And, I’ve never quite got the ‘hay’ thing, either, but I do get ‘grassy’ from some virginias.

Going back to the wine tasting thing, I’ll share a story. As a novice wine-guy, I one day found myself sitting in a big room with a bunch of other pretty much novice-folk, and at the end of the table was Robert Mondavi. Bob was a legend in the Napa valley at the time, and we were all feeling, at least I was, more than a little intimidated to be doing a wine tasting with him. There were glasses and pens and little pads of paper in front of each of us, and he gave us the instructions. Smell the wine. Swirl it in the glass. Smell again. Write down what you notice. Then, taste. Aerate the wine over your tongue. Breathe retro-nasally. Notice and write. Then, we’d discuss.

We all pretty much froze.

“Don’t worry. There are no wrong answers,” Bob said. (Turns out, he was one of the nicest, most down-to-earth guys you could ask to meet.)

So, we did it—sniff, swirl, sniff, scribble, taste, slurp, whooosh, scribble—and then started discussing. Our experiences were often quite different from one another, but the more we talked, the more we all learned, and the more we began to taste. Someone says dried apricot, and even if you didn’t taste it the first time, there’s a chance you might the second. Or the third. It’s a process of development.

In describing Laurel Heights, I wrote, “The flavours are deep and round […] subtle notes of orange peel, roasted oats, leather and peat. The smoke develops richness as it progresses, delivering a long, clean finish […] hints of malt and grapefruit.”

Believe me, it took quite a few bowls to dig all that out of there but I’ve since had more than one person tell me they can discern every one of those flavors, even if it was a bit of a stretch. Others have told me they found things that I missed. Excellent! One of the reasons I like reading the more thought provoking reviews of my own products is to read about others perceptions of things that I’d missed.

The point is, developing the vocabulary is just a matter of doing it. If you think you taste grilled hamburgers, write it down. (Tasting an aged tin of Mephisto, once, I tasted BBQ brisket. True.) See how your perceptions change and evolve over time. It’s fun, and it may or may not enhance your enjoyment. If it doesn’t, it’s easy enough to stop. 😉

Enjoy,

Greg

I have found that it helps me to ask my girlfriend, Laura, to smell an opened tin of tobacco and tell me what it smells like. Then I smell it again, and I can detect what she got. I also asked her son once when he was here.

Some of the tin aromas I was able to write about in past reviews that I only detected after asking someone else to take a whiff have been; barbecue, Fig Newtons, raisins. Actually, I personally detect raisins and apricots quite often.

I’m still searching for a “old bicycle inner – tube” blend. 😉

Next time I get a flat, Kevin, I’ll hook you up.

-glp

“I have always hd trouble identifying, putting words to some tobacco blends I taste. Straight VA for instance. Comforting aroma for sure. They call it sweet tasting, haylike, etc. I never would in a million years come up with grassy, haylike taste …. hope to see some suggestions on my question.”

A thought for Tony. I don’t find straight Va. to taste like the taste of hay but it’s taste is reminiscent of the smell of hay! Smell and taste are inextricably bound together (as in wine again). The plot deepens.

I find compound flavors to be a stumbling block, especially when the marriage is thorough. One famous example is McClelland’s description of their tinned blending Perique: “…somewhere between the fragrance of cooked fruit and the mustiness of mushrooms…”

Now, that takes some powerful imagination — identifying a flavor as some esoteric combination of olfactory memories. Nonetheless, I think McC’s call is pretty close on that one, but only because I can taste it and reflect on their observations.

In this regard, I’m beginning to practice with food, trying to envision the result of spice combinations.

Compound flavors do muddy the waters a little. A couple different things can happen. Two or more different tastes can each retain their own identities, though more difficult to distinguish because of the combination, or they can integrate so completely that they form an entirely new taste. I’d speculate that the latter is rather rare, but warrants further investigation.

For me, much of the fun is in the exploration, and the more we pay attention to what we taste, the more we taste. The naming of flavors and aromas isn’t the important part, but it’s a useful technique for focusing the attention. If you look at a brick wall, you see a brick wall. If you count the bricks, you see the wall in a completely different way. Recording our observations when we enjoy a smoke is just a way of “seeing” our experience in a different light.

I enjoyed reading your article Greg. I’ve been smoking a pipe for going on 28 yrs and am just now beginning to taste the differences in the tobaccos that make up a blend. Don’t know why it has taken me this long. May be that I just didn’t concern myself with the type of tobacco, but more so with did I like the blend or did I not like the blend. I can pick out latakia in blend, but who can’t. Now when it comes to oriental and turkish I have a problem. Perique makes itself known quite well. Virginias have got me stomped, unless I’m smoking a straight Virginia. When I smoke a pipe I find I enjoy it less if I try to disect the blend. At my age (63) my taste buds arn’t what they used to be and my sense of smell is going very quickly. Although I agree with everything you’ve written and I still try to pick out the various tobaccos in a blend, I gain more pleasure from just sitting back and not worry about the ingrediants. I have the upmost respect for your expertise and your blends, but I guess you just can’t take the Codger out of the Old Codger. Thanks Greg for all you do for us .

__________________

It´s not easy to learn the differenses when you never know for sure what the blenders do with the tobacco. To have a chance getting it right i guess you need to have all the baccy fresh from start, no blenders involved. I have smoked so called 100% perique from blender and the original stuff from DA MAN and it was not the same stuff in a million years not the same baccy even. The differense was like water VS 100% alcohol so for a mortal like me it´s very hard to notice the differense.

I am in agreement with you Greg, especially the approach that if we are going to do something, why not do it with some intellectual engagement and curiosity.

Here’s something I wish was available – a chart of typical flavors to look for from principal tobacco types of blends – we have a great poster of wine flavors in our bar, everything from plums to stones to butter, leather, peat etc.,. each pictured in a grid of wine glasses, something we picked up in Argentina at Mendoza, so it is in Spanish as well, just for fun.

But following on what you say about being able to find a line of flavor after it is pointed out, there must be many pipe smokers like me who are self-taught, and don’t really know what to look for in an oriental, or perique, or red virginia, gold, burley etc.,.

Not the primary and obvious – we all get the raisins and stewed fruit in stoved sweet virginia, or the nutty toasty oatmealy elements of burley. What I am talking about is a reference point for common, less common, and unusual elements in the major tobacco groupings. And somebody explaining what the dickens tonquin or deertongue or some of the more esoteric toppings and flavorings resemble.

I can “get” the dominant notes in many popular tobacco – the anise in Orliks Golden Flake, the vinegar in so many MacLelland blends, caramel/vanilla in some virginia flakes. But what else might I be looking for and what is the universe and lexicon of possible notes and flavor? I suggest the business of tobacco is perhaps behind the times in relation to other “tasted” products in not being more forthright and providing better education for the interested consumer. Descriptions like “a sophisticated blend sure to satisfy all the day through” I find baffling. Hat’s off to you as I have found your labeling among the most straightforward and descriptive, and as a result I will try any blend you bring out on faith of the description if it suits my tastes by description. But having a more organized frame of reference sure would help me raise my level of understanding.

that´s my thought too if i only know english better it´s what my post would have said.

Great comments, gentlemen. And some wonderful ideas presented. I like the idea of presenting the different inherent tastes of different leaf. This is complicated, however, by the new flavors and aromas that arise from combinations of multiple tobaccos, and the additional characteristics that arise from aging, especially when aging in these combinations.

Yesterday, I opened a ten year old tin of Ashbury. Even though I’ve had quite a bit of experience with aged weeds, and even though I know this tobacco very well, I was nevertheless surprised by what I found in the aromas from that tin. It was remarkable. Dozens of new smell and tastes, few of which would be found in a new tin, or in the individual components aged as long. It’s a living thing!

-glp

the pipemeetings at Vollmer&Nilsson is often a deepdive in aged tobaccos and what is a better spice to a smoke, then good friends and food.

I am smoking G.L. Pease Westminster right now, and on a re-light 2/3rds through the bowl, I got a little taste of Pizza crust, like when you get a piece that is a little burnt on the bottom.

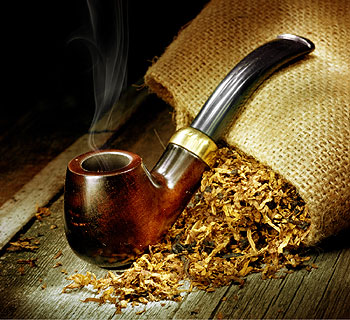

Side note: The tin of open tobacco pictured at the beginning of this article is actually G.L. Pease Westminster, and the actual tin I am smoking right now.

And at the end of the bowl it tastes like Cafe Mocha.

Mr. Pease I really like that guy’s chart idea. Granted it would take alot of the mystery out of some blends but hey man it would,in my opinion, help jumpstart new pipesters. And more ladies may fair well in considering taking up our art by knowing that aromas and tastes aren’t all masculine and tuff guy oriented.

I’m gonna straight up ask you. Will you consider putting together a baic chart?

The best time for me to find out those intricate tastes and smells in pipe tobacco is the early morning or the late night, when the air is fresh and other unknown conditions make my perceptions more sensitive. In other times I feel my self numb and can hardly taste what I am smoking; I know this is a sin for a pipe smoker. And yes, when one figure out certain taste in a pipe tobacco, it brings back–most of the times– a memory closely connected to it. It is, then, something similar to rejoicing in an imaginary world of memories and feelings. Taste and smell have such magical effect when it comes to memories; it is as if you live those past moments with all the feelings associated with them in a flash.

One thing left I couldn’t achieve; it is to decide what is this or that little taste in the tobacco. But I like this game, I think it develops our sensory and intellectual faculties although each of two is somehow opposite of the other.

I’ve found that the Pipe Tool App for iPhone has been a tremendous aid in helping me to recognize and keep track of the various blends I come across in my quest to broaden my tastes in tobacco. I have old favorites and relatively new favorites, but the habit of trying something new every month or so has greatly enhanced my enjoyment of the pipe. Thanks, Mr. P, for an excellent article.