It’s no secret that I love old pipes. Like a well broken-in pair of jeans, there’s something they bring with them that makes them sort of special. They carry an unspoken history with them; the places they’ve been, the tobaccos they’ve seen. Sometimes, this history is evidenced by the knocks and dings they show, or the aromas and tastes of tobaccos long since forgotten. Depending on how poorly it’s been treated, this can make an old pipe rather less than desirable, but a well cared for briar from eras past can be, or can become, a cherished favorite.

Some collectors I’ve spoken with have insisted that old pipes are better than new ones. How often have we heard, “They just don’t make ‘em like they used to?” There may be some validity to this, but I’m not convinced this sort of universal statement is true, or even necessarily a positive one. Let’s look a little closer, first at pipes of olde, and see if we can make some informed speculations.

At the zenith of the pipe’s history, at least with respect to popularity, pipes were made and sold by the millions. Manufacturers across all quality levels procured briar by the ton, not by the piece, and the best makers performed whatever magic they felt appropriate to ensure a good smoking result, always with an eye towards differentiating their pipes from those of their competitors. Some air dried their briar for long periods, others force-dried their briar more quickly in klins. The final processes of sorting, grading and finishing was sometimes a closely guarded secret amongst makers, with only the finest pieces finding their way down the line to being sold as top grade pipes.

Additionally, various techniques were often employed after the pipe was machined, such as Dunhill’s famous “oil curing,” used as part of the finishing process for their legendary “Shell” sandblasts. Sasieni was said to “oven-cure” turned bowls, subjecting them to tortuous heat over a prolonged period; those that survived the ordeal were reputed to be very dry smokers.

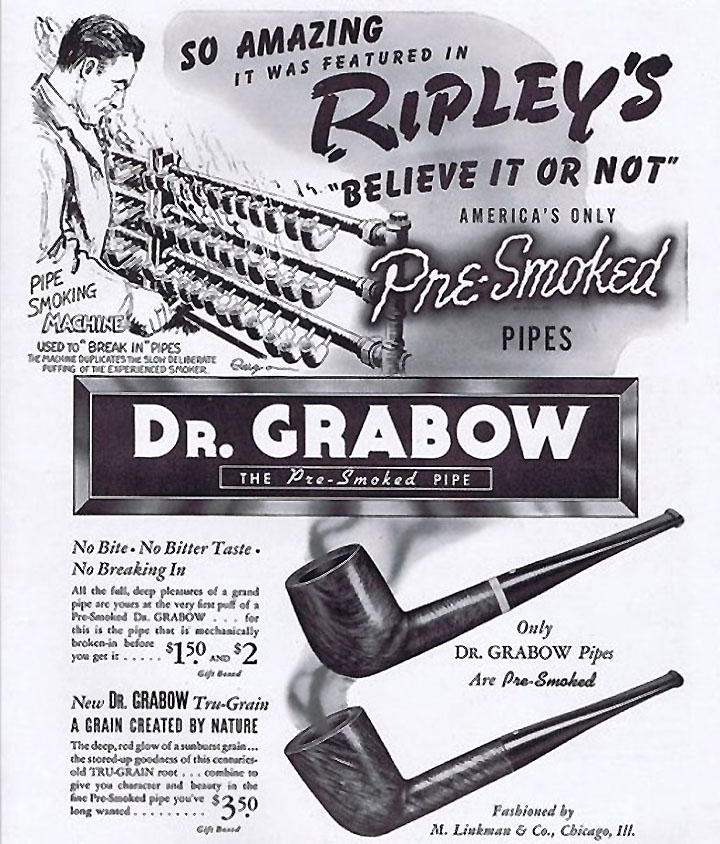

Of the more budget friendly brands, the Dr. Grabow “pre-smoked” pipe, employed what is likely the most dramatic “curing” method. Using a technique developed by Louis B. Linkman in 1933, finished pipes were filled with tobacco, smoked gently to the bottom by his Automated Smoking Machine, the process repeated several times. This was, if nothing else, a stroke of marketing genius. Inexpensive as they were, the briar used to make Dr. Grabows was arguably not especially consistent or well cured, which would result in at least some pipes tasting bad out of the gate. The smoking machine could mitigate the potential harshness of those early bowls without suffering the torment a human smoker would, allowing lesser quality briar to be made into acceptably good smoking pipes.

One thing is certain. Of the millions of pipes made each of those golden years, some were certainly exquisite, many were likely dreadful, and the majority fell somewhere in between these extremes. Pipes then, especially those in lower price categories, were seen as tools, simple items to buy, use, and occasionally discard. It’s probable that the worst of them simply never survived to share their horror with us today. Even if a pipe was good and smoked heavily, it would eventually reach the end of its useful life, either through just being “smoked out,” or suffering a broken tenon or bitten through stem or other misfortune, and find itself cast aside. Only “special” pipes, the favorites, the best of the best, would be lavished with sufficient care to allow them to survive the decades in relatively good nick. So, when we find old pipes, at least those from the makers with good reputations, they are more likely to be accidentally curated specimens rather than overall representative examples. If we add to the equation the fact that old pipes, again, if well cared for, have already been thoroughly broken in, we are likely to find some true gems amongst the antiquities.

So, are old pipes really “better?” What about today’s low volume pipe makers who operate in a rather different environment? Because today’s demand for briar is significantly lower, suppliers can be more careful in choosing and cutting burls. They’ll cut blocks to maximize their quality, or at least their grain consistency, rather than to achieve the burl’s greatest yield. Too, they can spend more time ensuring that the wood they sell is carefully boiled and dried sufficiently to deliver consistently good smoking.

The pipe maker can then do whatever is in their bag of tricks to further increase the probability that the pipe they make is an exceptional one, lavishing great care on all the subtle details of its creation. Additionally, with today’s ease of information exchange, and perhaps somewhat less of a tendency towards competition, a lot of experimentation has been performed and shared, along with some pretty detailed analysis of what has worked in the past, and what may not have. The result is that more is probably known today than ever before about what makes a great pipe, and what doesn’t, which certainly benefits us as pipe smokers.

In terms of artistry, witnessing the exploration some makers have taken in creating new shapes and forms can be a remarkable adventure in its own right. And, there are more choices to be found for interesting stem materials, including improved vulcanite that is less resistant to oxidation than much of what was available in the past, and custom-cast acrylic that presents the smoker with more choices of color and style than ever before.

Though probably not universally true, even amongst “high volume” manufacturers, today’s lower demand can result in greater care in briar selection, with advances in technology arguably creating increased consistency in construction. There are many factory pipes at affordable prices that rival the best the past had to offer.

I’ve got a lot of beautiful old pieces in my collection that are brilliant smokers, including the one I’m puffing on as I write this. Not all of them have been, though, and some have been absolute dogs. Out of the many vintage GBDs, Comoys, Barlings and even Dunhills that I’ve had, a handful have stood out as extraordinary, while many have been just okay, or even pretty awful.

At the same time, many of the newer, artisan made pieces that I have are amongst the finest pipes I’ve ever smoked, and a good percentage of the modern factory pipes I’ve experienced have been superb. There’s no doubt that there are many wonderful vintage pieces available to us, some of them fabulous smokers and exquisite examples of the pipe’s long heritage, but in looking at the bigger picture, it seems safe to say today’s pipe may well represent the best that pipe making has ever offered. Maybe they don’t make ‘em like they used to. Maybe they make ‘em better.