Blowing that up, even I can see the city mark is Chester. I guess it is in fact a 1914 mark. Thanks for the discussion fellas.

Help with Hallmarks

- Thread starter xrundog

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

SmokingPipes.com Updates

Watch for Updates Twice a Week

Yep, Chester 1914. Glad we have some good silver sleuths on the board.

Yep, Chester 1914. Glad we have some good silver sleuths on the board.

That last photo did the trick. I could have sworn that middle mark was the uncrowned lion from London in the first photos.Blowing that up, even I can see the city mark is Chester. I guess it is in fact a 1914 mark. Thanks for the discussion fellas.

(Damn old eyes and too small screen on my phone!)

That last photo did the trick. I could have sworn that middle mark was the uncrowned lion from London in the first photos.

(Damn old eyes and too small screen on my phone!)

LOL, and I thought it was the London crowned leopard, just worn down:

I’m glad @greeneyes posted the correct hallmark.

S

Sure, if those are your real initials!

I've been debating whether to dump the Withecomb proverbial bag in this thread for the last week or two; the pro side was that it's opportune, which is a tactful way of saying that it seems unlikely that anyone will ever be very interested in Withecomb again anytime soon. The con side is that it takes time and effort to organize material, both of which are in short supply right now. I decided to compromise by offering a brief summary, or what Ehrlichman in another context famously called a modified limited hangout. So here we go...

John William Withecomb (1801-1847), an excise officer in Manchester, married Mary Rosetta Newlyn (1803-1875) in 1822 in the village of Cobham in the county of Kent. John William's career as an excise officer appears to have been slightly checkered. In 1836 he, along with two colleagues, was accused of "having purloined a quantity of soap". The evidence cited in the local newspaper looked pretty damning to me but after a trial following a brief stay in Bridewell prison John and his partners beat the rap, luckily for his wife Mary Rosetta and their children. Speaking of which when he wasn't not-stealing stuff John & his wife found time to raise two sons and three daughters. The sons were Charles (1827-1894) and the hero of our tale, Thomas Robert (1840-1921), hereafter referred to as TRW.

It's worth noting that Charles, older than his brother by some 13 years, did not follow their father into the excise profession. Instead he became a jeweler and by the age of 24 was already employing a man to help out in his growing business. All the evidence I’ve seen suggests that Charles was the first member of his extended family to become a jeweler. Notwithstanding the somewhat sticky allure of free soap TRW decided to follow in Charles' footsteps, not their father’s, and by 1861 was listed in the census as a working jeweler. From there succeeding censuses show him following the not unfamiliar path from jeweler to cigar merchant to tobacconist. In 1862 young TRW established his own business in Manchester. The shop was originally located at 28a Victoria Street in Manchester. In the Spring of 1870 TRW relocated to an address very close by, at 32 Victoria Street, and there he remained until December 1884. At that point TRW settled in at a new location, again nearby, at 16 & 18 Victoria Street. This proved to be a lasting address for the business, and TRW’s shop continued to occupy these premises for the next fifty years. Along the way TRW added two branch locations; one at 66 Market Street (opened in December of 1875, closed sometime after 1920), and one at 2 Hanging Ditch (opened by early 1889, closed sometime after 1904).

Like so many early participants in the industry TRW tried his hand at innovation. In his case inspiration struck twice. The first time was shortly after he opened his shop. On November 13, 1863 TRW received a patent for what he later advertised as Withecomb’s Patent Anti-Nicotine Screw Pipe Band (a catchy, if vaguely obscene title). Here is a copy of the original submission as approved by the patent office. The copperplate script is for modern eyes a bit difficult to read; for the very curious I’ll be glad to provide a transcription:

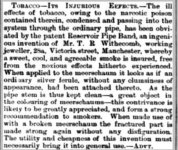

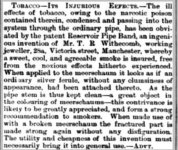

Interestingly what is a common practice today was already in use over a century and a half ago, to wit advertisements masquerading as news. Here is an early notice placed in many newspapers by TRW touting the advantages of his invention, which included improved health, pleasure in smoking, aesthetics, tensile strength, and thrift. Only at the end does he coyly acknowledge this valuable information is an “advt”:

TRW’s second innovation, the “wide-bore” mouthpiece, was apparently introduced in the late summer of 1871. It wasn’t until the beginning of 1878, however, that TRW began to issue vaguely minatory notices that the wide-bore was a registered design and under legal protection as his intellectual property. Why the 6+ year delay took place I have no idea unless changes in design law began to allow ownership rights previously unavailable.

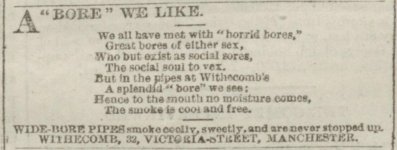

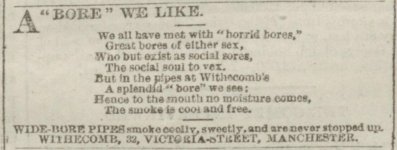

Beyond threats, of course, here too advertising played its role, in this case in the form of tedious doggerel. It’s fashionable to look down on Victorian verse but between Tennyson, Hopkins and Browning I have to believe WIthecomb could have done better than this:

Two other quick remarks:

- for several reasons I don’t believe that TRW ever submitted a hallmark to the London assay office. I do know of three TRW submissions to the Chester office, which was the closest to Manchester in the 1800s, three all dating from the late 1880s through the mid 1890s.

- from the opening of the shop in 1862 and for some time thereafter TRW focused on meerschaum pipes and cigars. When he did begin to offer briars the most commonly mentioned brands in his ads were GBD and BBB; unsurprising since these were two of the leading makes sold in the English market at that time. The pipes themselves, of course, were French.

At this point I need to backtrack a little to fill in some relevant background on TRW’s nuclear family. In 1866 TRW married Jane Williams (1848-1886), and true to the custom of the time TRW and Jane immediately began to procreate as if their lives depended on it. In the eighteen years following their marriage the couple had nine children, of whom four were sons: Percy (1868-1930), Frank (1870-1929), Thomas Robert jr (1874-1953), and Charles (1876-1930). All four sons were eventually involved at some point in their father’s business. Here things get a bit murky.

If you believe the puff piece in a city directory dating from 1888 TRW was well liked in Manchester; it was said of him that he was “…well known in the city, and his genial disposition makes him a great favourite with all who love to blow a cloud or who fancy they can tell a good cigar when they see it.” This I actually believe, at least as far as his customers were concerned. It’s a rare shopkeeper that can thrive by alienating his trade. What he’s like around his family may be another matter. This is pure speculation but reading between the lines I think TRW had what we would today call control issues. The signs are faint but present. They include a) a failure to modify the name of the business to TR Withecomb & Sons until a couple of years before his death, by which time his sons had been active in the shops since the 19th century and were all between forty and fifty years old; b) a will that he only got around to preparing four days before his death; c) references in earlier censuses to his sons as “assistant tobacconists” after they’d been working at the shop for decades; and d) the retention by TRW of the position of managing director until the very day he died. Are each of these factors, or all of them together, understandable? Of course. But it does suggest the pattern of a man with a profound reluctance to hand over the reins.

Also interesting is the treatment of his namesake, Thomas Robert Withecomb junior (actually the “junior” part doesn’t appear anywhere that I’ve found, but I use it here to make it easy to distinguish between father and son). What actually happened is unclear, but the result is not. Although involved in his father’s business as a young man, at the time of TRW’s death in 1921 TRW jr is clearly and completely left out in the cold. We often hear the phrase “cut out of the will”. I’ve reviewed scores of English wills from the 19th and 20th centuries and for this to actually happen in practice is very rare indeed. But TRW jr not only inherits nothing in his father’s will he’s not even mentioned in it. Alone of all the children he is omitted, alone of all the children he gets nothing. Ironically this may have contributed to the ultimate demise of the business.

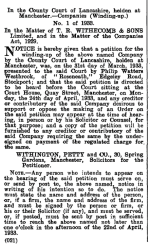

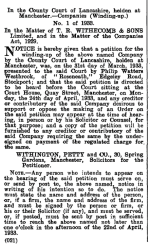

When TRW died he left a third of the business to son Percy, a third to son Frank, and a third to be split between all the remaining children, with two exceptions: TRW jr, who as already noted is not mentioned at all, and one of the five daughters, Edith (1878-1958), who suffered from mental illness and received her inheritance in the form of an annuity to ensure continuity of care. TR Withecomb & Sons only survived its founder by about a dozen years. Whether it was the advent of the Great Depression, or the death in quick succession of TRW’s heirs I don’t know. But what happened to the male line is telling. TRW’s son Frank had two sons of his own, the older one named Leslie. He died in August of 1928. In April of 1929 Frank himself died. Percy died in February of 1930. And in September of 1930 the last of TRW’s sons, Charles, died too. At that point the only male heir left was Frank’s younger son Frank Douglas (1901-1979). Whether he was not active in the family business, or whether he was involved but too young to salvage it after everyone else had died, I have no idea. I do know that TR Withecomb & Sons entered insolvency in 1933 and was ordered wound up in 1935. Meanwhile the disinherited son, TRW jr, lingered on for another twenty years before dying on December 6, 1953. Would things have gone differently if he’d stayed involved in the family business? Impossible to know.

I have lots more on TRW and his family but it largely qualifies as trivia, and the end of the business is a good place to end this summary.

John William Withecomb (1801-1847), an excise officer in Manchester, married Mary Rosetta Newlyn (1803-1875) in 1822 in the village of Cobham in the county of Kent. John William's career as an excise officer appears to have been slightly checkered. In 1836 he, along with two colleagues, was accused of "having purloined a quantity of soap". The evidence cited in the local newspaper looked pretty damning to me but after a trial following a brief stay in Bridewell prison John and his partners beat the rap, luckily for his wife Mary Rosetta and their children. Speaking of which when he wasn't not-stealing stuff John & his wife found time to raise two sons and three daughters. The sons were Charles (1827-1894) and the hero of our tale, Thomas Robert (1840-1921), hereafter referred to as TRW.

It's worth noting that Charles, older than his brother by some 13 years, did not follow their father into the excise profession. Instead he became a jeweler and by the age of 24 was already employing a man to help out in his growing business. All the evidence I’ve seen suggests that Charles was the first member of his extended family to become a jeweler. Notwithstanding the somewhat sticky allure of free soap TRW decided to follow in Charles' footsteps, not their father’s, and by 1861 was listed in the census as a working jeweler. From there succeeding censuses show him following the not unfamiliar path from jeweler to cigar merchant to tobacconist. In 1862 young TRW established his own business in Manchester. The shop was originally located at 28a Victoria Street in Manchester. In the Spring of 1870 TRW relocated to an address very close by, at 32 Victoria Street, and there he remained until December 1884. At that point TRW settled in at a new location, again nearby, at 16 & 18 Victoria Street. This proved to be a lasting address for the business, and TRW’s shop continued to occupy these premises for the next fifty years. Along the way TRW added two branch locations; one at 66 Market Street (opened in December of 1875, closed sometime after 1920), and one at 2 Hanging Ditch (opened by early 1889, closed sometime after 1904).

Like so many early participants in the industry TRW tried his hand at innovation. In his case inspiration struck twice. The first time was shortly after he opened his shop. On November 13, 1863 TRW received a patent for what he later advertised as Withecomb’s Patent Anti-Nicotine Screw Pipe Band (a catchy, if vaguely obscene title). Here is a copy of the original submission as approved by the patent office. The copperplate script is for modern eyes a bit difficult to read; for the very curious I’ll be glad to provide a transcription:

Interestingly what is a common practice today was already in use over a century and a half ago, to wit advertisements masquerading as news. Here is an early notice placed in many newspapers by TRW touting the advantages of his invention, which included improved health, pleasure in smoking, aesthetics, tensile strength, and thrift. Only at the end does he coyly acknowledge this valuable information is an “advt”:

TRW’s second innovation, the “wide-bore” mouthpiece, was apparently introduced in the late summer of 1871. It wasn’t until the beginning of 1878, however, that TRW began to issue vaguely minatory notices that the wide-bore was a registered design and under legal protection as his intellectual property. Why the 6+ year delay took place I have no idea unless changes in design law began to allow ownership rights previously unavailable.

Beyond threats, of course, here too advertising played its role, in this case in the form of tedious doggerel. It’s fashionable to look down on Victorian verse but between Tennyson, Hopkins and Browning I have to believe WIthecomb could have done better than this:

Two other quick remarks:

- for several reasons I don’t believe that TRW ever submitted a hallmark to the London assay office. I do know of three TRW submissions to the Chester office, which was the closest to Manchester in the 1800s, three all dating from the late 1880s through the mid 1890s.

- from the opening of the shop in 1862 and for some time thereafter TRW focused on meerschaum pipes and cigars. When he did begin to offer briars the most commonly mentioned brands in his ads were GBD and BBB; unsurprising since these were two of the leading makes sold in the English market at that time. The pipes themselves, of course, were French.

At this point I need to backtrack a little to fill in some relevant background on TRW’s nuclear family. In 1866 TRW married Jane Williams (1848-1886), and true to the custom of the time TRW and Jane immediately began to procreate as if their lives depended on it. In the eighteen years following their marriage the couple had nine children, of whom four were sons: Percy (1868-1930), Frank (1870-1929), Thomas Robert jr (1874-1953), and Charles (1876-1930). All four sons were eventually involved at some point in their father’s business. Here things get a bit murky.

If you believe the puff piece in a city directory dating from 1888 TRW was well liked in Manchester; it was said of him that he was “…well known in the city, and his genial disposition makes him a great favourite with all who love to blow a cloud or who fancy they can tell a good cigar when they see it.” This I actually believe, at least as far as his customers were concerned. It’s a rare shopkeeper that can thrive by alienating his trade. What he’s like around his family may be another matter. This is pure speculation but reading between the lines I think TRW had what we would today call control issues. The signs are faint but present. They include a) a failure to modify the name of the business to TR Withecomb & Sons until a couple of years before his death, by which time his sons had been active in the shops since the 19th century and were all between forty and fifty years old; b) a will that he only got around to preparing four days before his death; c) references in earlier censuses to his sons as “assistant tobacconists” after they’d been working at the shop for decades; and d) the retention by TRW of the position of managing director until the very day he died. Are each of these factors, or all of them together, understandable? Of course. But it does suggest the pattern of a man with a profound reluctance to hand over the reins.

Also interesting is the treatment of his namesake, Thomas Robert Withecomb junior (actually the “junior” part doesn’t appear anywhere that I’ve found, but I use it here to make it easy to distinguish between father and son). What actually happened is unclear, but the result is not. Although involved in his father’s business as a young man, at the time of TRW’s death in 1921 TRW jr is clearly and completely left out in the cold. We often hear the phrase “cut out of the will”. I’ve reviewed scores of English wills from the 19th and 20th centuries and for this to actually happen in practice is very rare indeed. But TRW jr not only inherits nothing in his father’s will he’s not even mentioned in it. Alone of all the children he is omitted, alone of all the children he gets nothing. Ironically this may have contributed to the ultimate demise of the business.

When TRW died he left a third of the business to son Percy, a third to son Frank, and a third to be split between all the remaining children, with two exceptions: TRW jr, who as already noted is not mentioned at all, and one of the five daughters, Edith (1878-1958), who suffered from mental illness and received her inheritance in the form of an annuity to ensure continuity of care. TR Withecomb & Sons only survived its founder by about a dozen years. Whether it was the advent of the Great Depression, or the death in quick succession of TRW’s heirs I don’t know. But what happened to the male line is telling. TRW’s son Frank had two sons of his own, the older one named Leslie. He died in August of 1928. In April of 1929 Frank himself died. Percy died in February of 1930. And in September of 1930 the last of TRW’s sons, Charles, died too. At that point the only male heir left was Frank’s younger son Frank Douglas (1901-1979). Whether he was not active in the family business, or whether he was involved but too young to salvage it after everyone else had died, I have no idea. I do know that TR Withecomb & Sons entered insolvency in 1933 and was ordered wound up in 1935. Meanwhile the disinherited son, TRW jr, lingered on for another twenty years before dying on December 6, 1953. Would things have gone differently if he’d stayed involved in the family business? Impossible to know.

I have lots more on TRW and his family but it largely qualifies as trivia, and the end of the business is a good place to end this summary.

When the subject was brought up a while back, I caught myself wondering how the name was pronounced. I thought briefly it might be pronounced "WHYTH-COMB" but, um, now I know it's meant to have as many syllables as "HORR-ID-BORES".

I hate to think about what the versifier meant by "social sores". In Victorian England they treated that kind of thing with mercury.

That’s Maurice Strauss and Henry Simon, at other times affiliated in various combinations with Emile Vuillard. That particular makers mark was filed in 1905.

Thanks for that. I take it you can’t make sense of the date code either.That’s Maurice Strauss and Henry Simon, at other times affiliated in various combinations with Emile Vuillard. That particular makers mark was filed in 1905.

The truth is I didn’t try. My eyes aren’t great and I do most of my pipesmagazine reading on my phone which offers very limited magnification. For a sound opinion I think Jesse has some of the best equipment, experience & judgment. If you still want a guess I’d say 1907.

Last edited:

I have the same problem. Even with magnification. Plus it seems like the craftsmen making the Chester stamps took some artistic liberty. Your guess is plausible. My guess without the hallmark was 1900 to 1920. Here’s the whole pipe for context.The truth is I didn’t try. My eyes aren’t great and I do most of my pipesmagazine reading on my phone which offers very limited magnification. For a sound opinion I think Jesse has some of the best equipment, experience & judgment. If you still want a guess I’d say 1907.

It looks to me like E struck twice, once upside down, and thus 1905.I have the same problem. Even with magnification. Plus it seems like the craftsmen making the Chester stamps took some artistic liberty. Your guess is plausible. My guess without the hallmark was 1900 to 1920. Here’s the whole pipe for context.

View attachment 338239

Cock-up, quick correction, and hey, who's going to care?

That last photo sure looks like Chester. With that curly Q date stamp I thought it might be Irish.

I’ll check it out later. Max is learning Photoshop. Be very afraid.The truth is I didn’t try. My eyes aren’t great and I do most of my pipesmagazine reading on my phone which offers very limited magnification. For a sound opinion I think Jesse has some of the best equipment, experience & judgment. If you still want a guess I’d say 1907.

I have the same problem. Even with magnification. Plus it seems like the craftsmen making the Chester stamps took some artistic liberty. Your guess is plausible. My guess without the hallmark was 1900 to 1920. Here’s the whole pipe for context.

View attachment 338239

Coincidentally, today I finally installed Photoshop on my workstation so that Max could start to learn it. Heh, heh, poor bastard...The truth is I didn’t try. My eyes aren’t great and I do most of my pipesmagazine reading on my phone which offers very limited magnification. For a sound opinion I think Jesse has some of the best equipment, experience & judgment. If you still want a guess I’d say 1907.

Onto this hallmark. I looked through three lists of Chester hallmarks and this doesn't fit any of them. Not only doesn't the date mark match anything, the shield shapes are wrong. Even the Chester stamping is off. I guess they made something custom for striking their stamping, but it's so customized as to be useless.

Sorry not to have better news.

Looks like a K on its back to me. So my pure guess is 1910.I have another weirdo fellas. Looks like the Chester city stamp. But I can’t figure the date code. I compared it carefully to the first two 20th century columns. It looks right stylistically, but I’m not experiencing the aha moment.

View attachment 338186