Several days ago I spoke with Rob Cooper ("Coopersark" on eBay) at some length about the importance of historical details, originality, and so forth to many pipe collectors.

In the course of that conversation Dunhill's "white spot" was mentioned as something which factored into determining authenticity in some cases, since it had varied in position, size, and material over the years. (The material being ivory for the first 40 or so years of the company's production, after which a more color-stable and less expensive plastic took its place.)

Rob mentioned in passing that he believed what everyone thought was ivory was actually celluloid, though, and always had been, because real ivory would never have been practical. It required too much labor to create thin, spaghetti-like rods from the stuff, regardless of its intrinsic expense. I responded that in the first half of the 20th century ivory was regarded as just another material, was commonly used for "tourist grade" trinkets from toothpicks to chopsticks, and could doubtless be bought cheaply in rod form from China or Japan, so Dunhill never DID shoulder the cost... the international differences in how much "a dollar was worth" (so to speak) took care of it.

Not able to settle the matter, our conversation moved to other things.

Afterward, though, because our points canceled each other out, the question started to eat at me. One of us had to be right, but how to know for sure? Dissolving an old dot and a new one with some sort of chemical, litmus-test-style, was doubtless possible, but I was no chemist... and unless the difference was dramatic and unarguable, nothing would be settled.

Grind to dust? Examine with a microscope? Because of the nature of the collecting hobby, if there was ANY element of subjectivity in interpreting the result of such a test, the question wouldn't be answered. The can would just be kicked down the road.

Then I came across an antiques site which said that real ivory doesn't burn (except at several thousand degrees, I suppose), and the tip of a sewing needle heated red-hot would leave no significant mark on it, while all known faux ivory materials would react somehow. Melt, blacken, or similar.

So, I searched through my stem discard box for an ivory-spotted Dunhill stem as a test subject. One that I wouldn't mind losing if the celluloid theory was correct.

Here is the stem. Three views to confirm authenticy --- in its entirety, the tenon, and the slot:

.

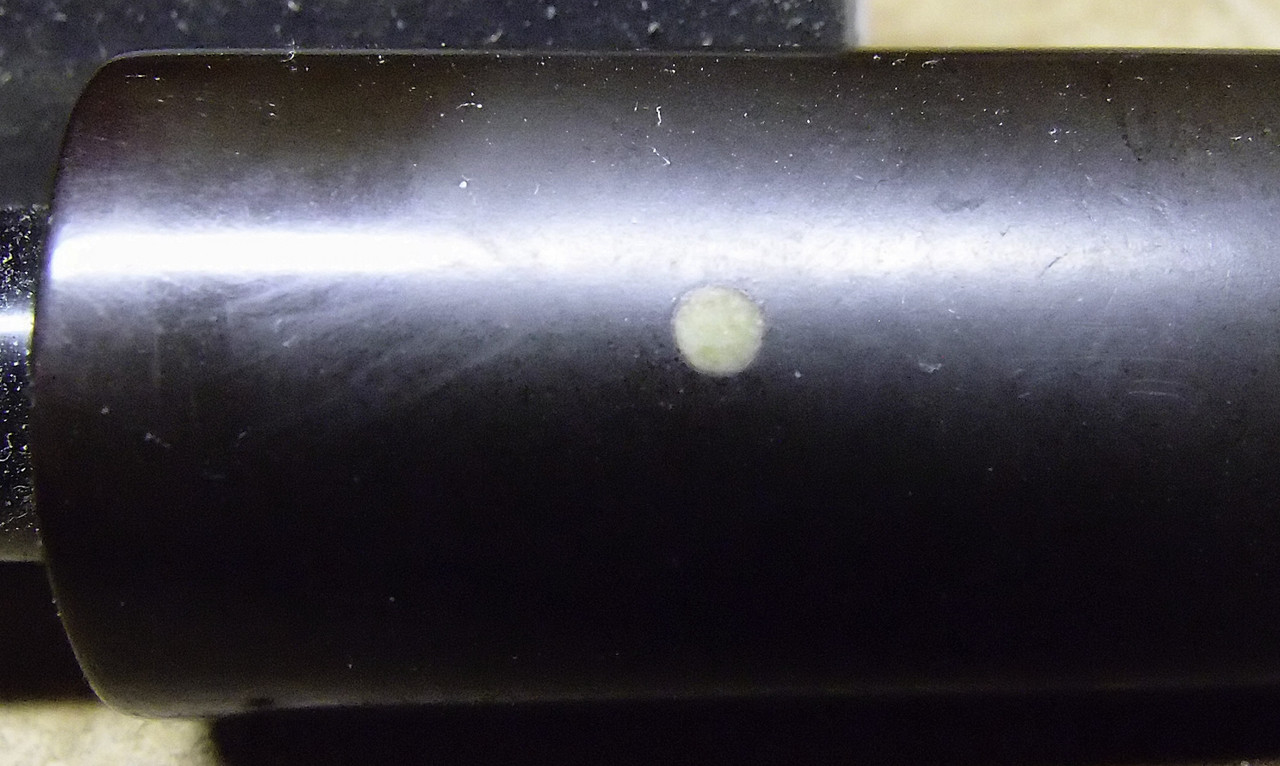

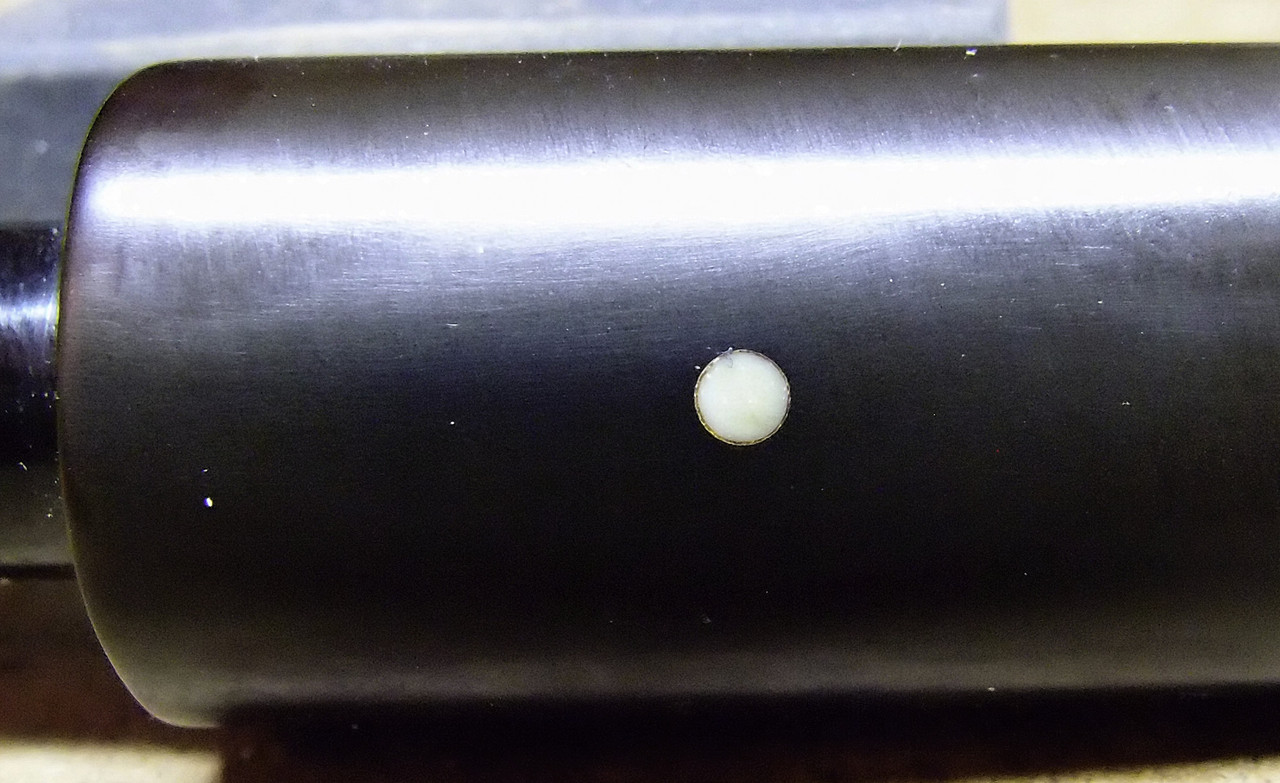

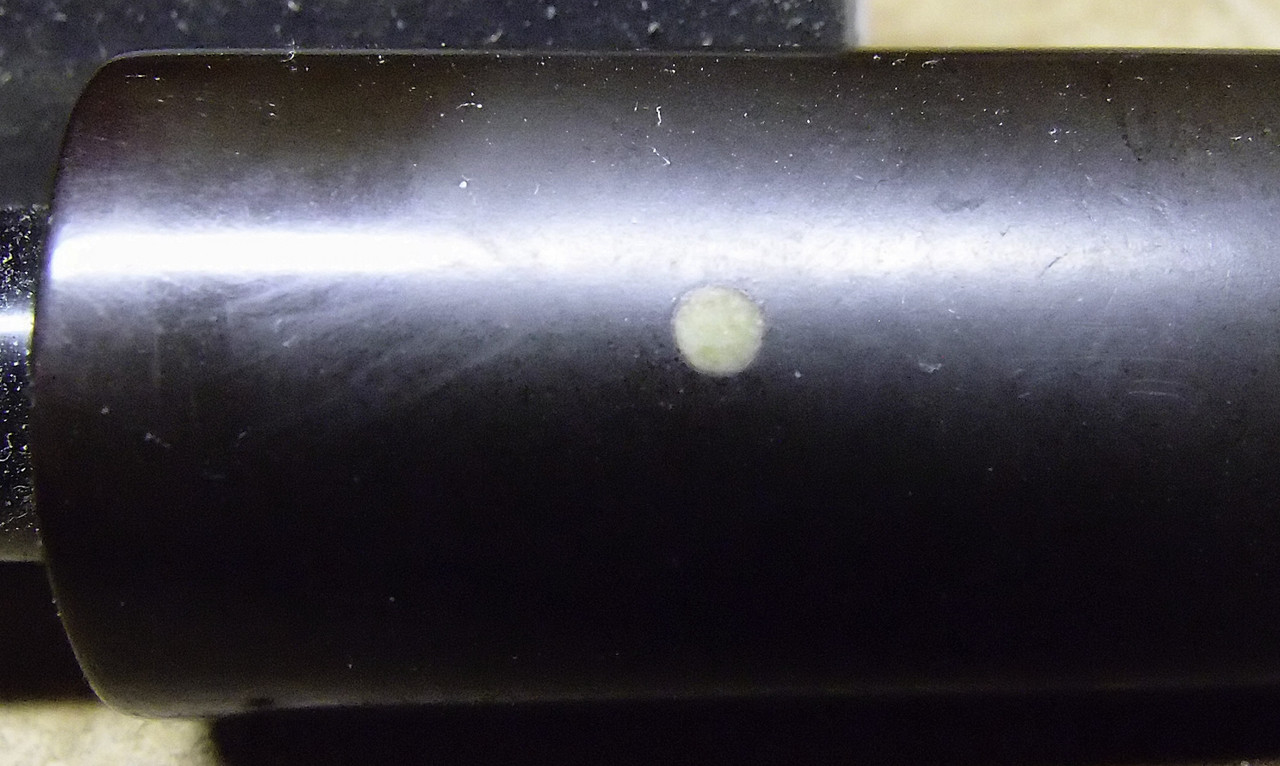

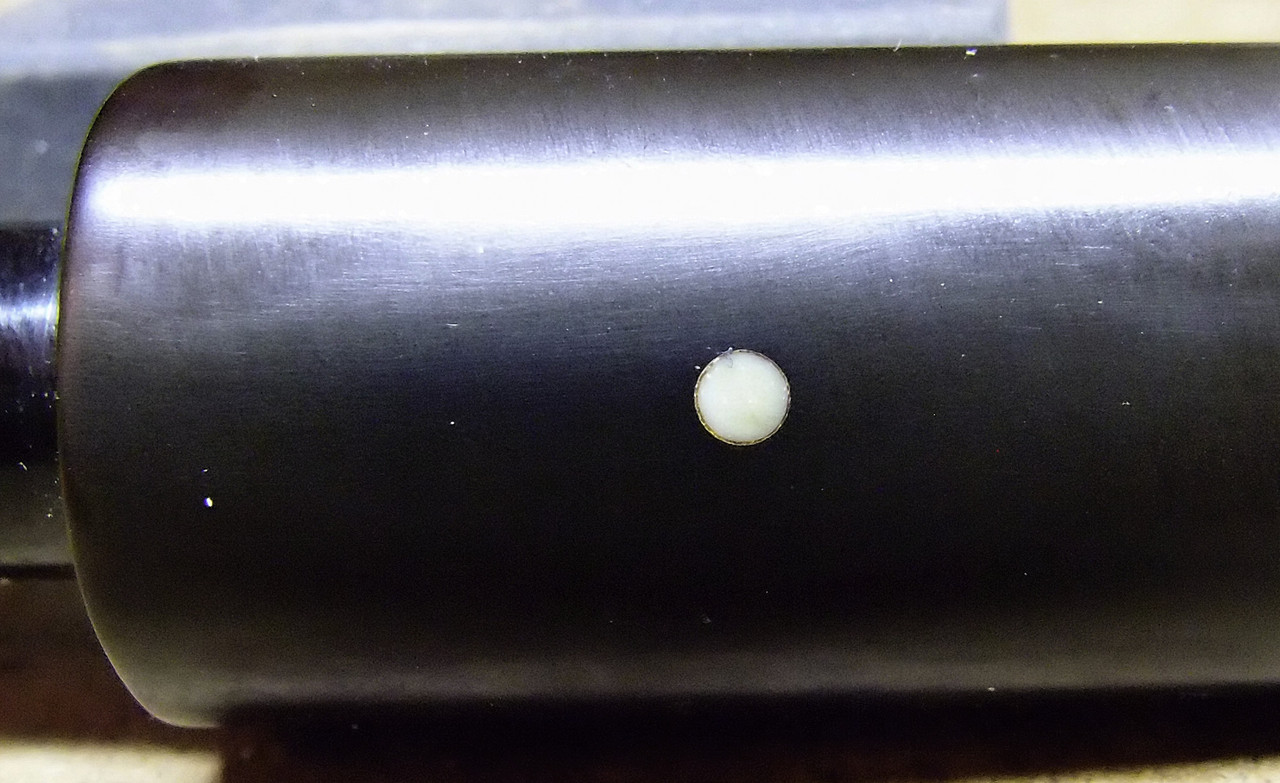

Here is a close-up of the spot before cleaning it off, and after. (I didn't want a possible layer of wax, dirt, etc. to burn and confuse things):

.

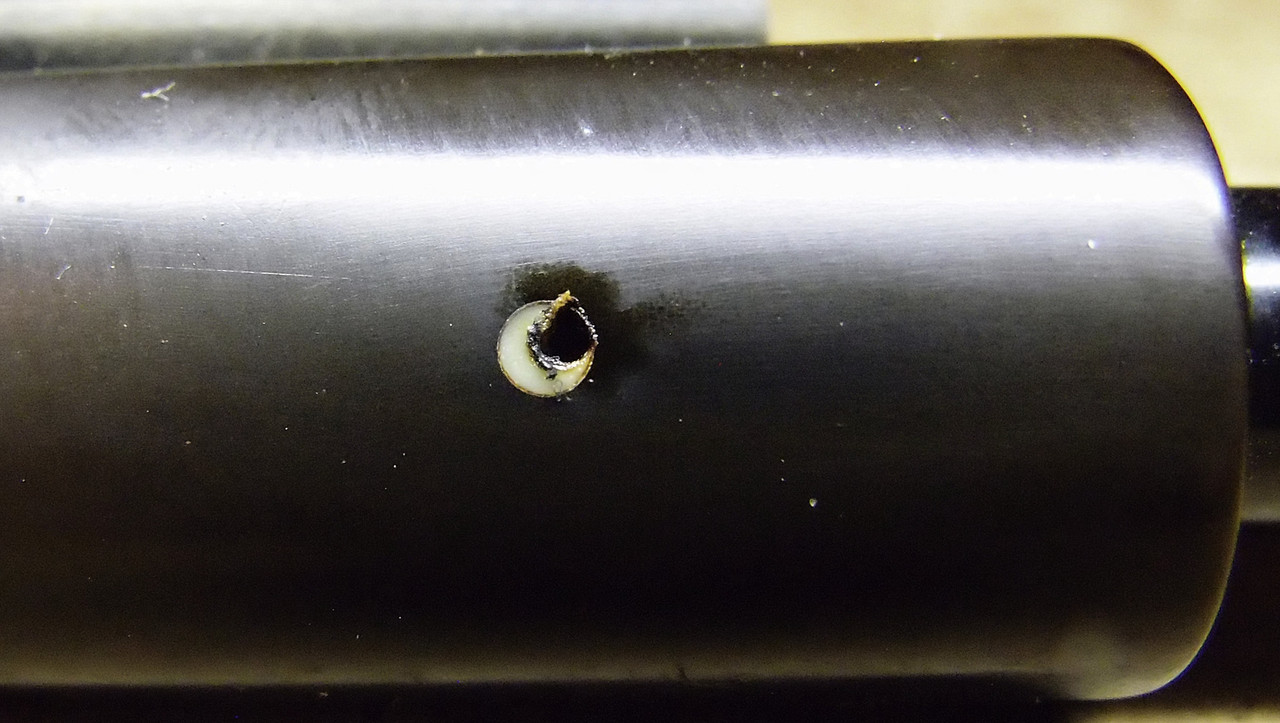

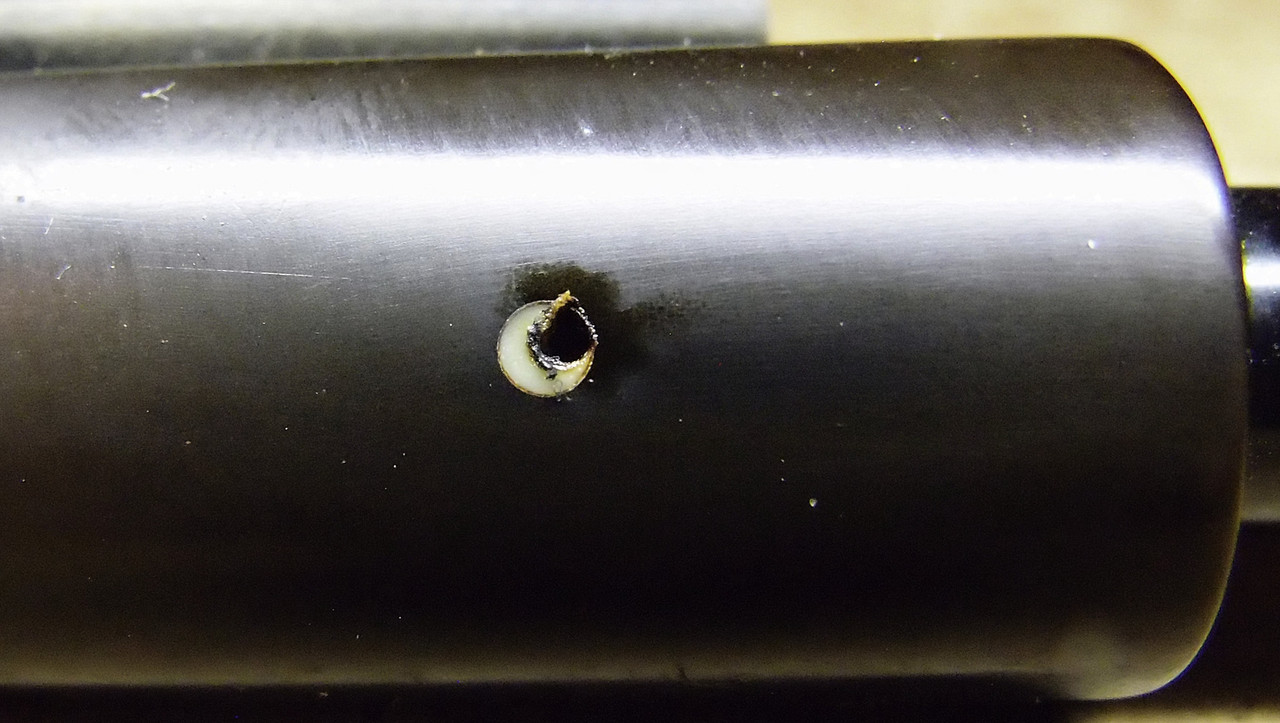

And this is the white spot after being touched by the red hot needle. It sunk in instantly and actually exploded in a gentle sort of way. A fizz-pop with a big puff of smoke.

It doesn't get more settled than that. 100%, proved beyond-the-slightest-shadow-of-a-doubt, those yellow/milky-looking Dunhill white dots---the early ones---are cellulose, not ivory.

Thank you Mr. Cooper. (There will doubtless many disillusioned Dunhill collectors in the world, but oh well. Facts are facts, and myths always die hard.) :lol:

In the course of that conversation Dunhill's "white spot" was mentioned as something which factored into determining authenticity in some cases, since it had varied in position, size, and material over the years. (The material being ivory for the first 40 or so years of the company's production, after which a more color-stable and less expensive plastic took its place.)

Rob mentioned in passing that he believed what everyone thought was ivory was actually celluloid, though, and always had been, because real ivory would never have been practical. It required too much labor to create thin, spaghetti-like rods from the stuff, regardless of its intrinsic expense. I responded that in the first half of the 20th century ivory was regarded as just another material, was commonly used for "tourist grade" trinkets from toothpicks to chopsticks, and could doubtless be bought cheaply in rod form from China or Japan, so Dunhill never DID shoulder the cost... the international differences in how much "a dollar was worth" (so to speak) took care of it.

Not able to settle the matter, our conversation moved to other things.

Afterward, though, because our points canceled each other out, the question started to eat at me. One of us had to be right, but how to know for sure? Dissolving an old dot and a new one with some sort of chemical, litmus-test-style, was doubtless possible, but I was no chemist... and unless the difference was dramatic and unarguable, nothing would be settled.

Grind to dust? Examine with a microscope? Because of the nature of the collecting hobby, if there was ANY element of subjectivity in interpreting the result of such a test, the question wouldn't be answered. The can would just be kicked down the road.

Then I came across an antiques site which said that real ivory doesn't burn (except at several thousand degrees, I suppose), and the tip of a sewing needle heated red-hot would leave no significant mark on it, while all known faux ivory materials would react somehow. Melt, blacken, or similar.

So, I searched through my stem discard box for an ivory-spotted Dunhill stem as a test subject. One that I wouldn't mind losing if the celluloid theory was correct.

Here is the stem. Three views to confirm authenticy --- in its entirety, the tenon, and the slot:

.

Here is a close-up of the spot before cleaning it off, and after. (I didn't want a possible layer of wax, dirt, etc. to burn and confuse things):

.

And this is the white spot after being touched by the red hot needle. It sunk in instantly and actually exploded in a gentle sort of way. A fizz-pop with a big puff of smoke.

It doesn't get more settled than that. 100%, proved beyond-the-slightest-shadow-of-a-doubt, those yellow/milky-looking Dunhill white dots---the early ones---are cellulose, not ivory.

Thank you Mr. Cooper. (There will doubtless many disillusioned Dunhill collectors in the world, but oh well. Facts are facts, and myths always die hard.) :lol: