July is a month of milestones for pipe smokers. You read that right. As the nation celebrates 245 years of independence, escaping from the clutches of rascally British King George III’s erratic rule, pipe smokers commemorate the history of pipes and tobacco that played a role in that history.

Another huge milepost is this month’s marking of the 59th anniversary of the death of William Faulkner, a Southern and American literary icon.

First, let’s travel back a couple of centuries when the U.S. was a rag-tag bunch of colonies. Except for a few historically central cities—like New York, Boston, Philadelphia, etc.— the nation was in many ways a land of farms and farmers.

Even the founders of liberty and signers of that dearest of all democratic documents, the Declaration of Independence, were farmers.

Many were pipe smokers and growers of tobacco. Some even chewed the leaf.

The history of tobacco in America pre-dates any record related to liberty and the war that set the nation free from King George III, an addlepated sovereign, who suffered from fits of insanity most of his life.

Without slogging through the thousands of years tobacco has been around, it became a leaf of note with Native Americans who introduced it to explorers who arrived on American shores.

Now, just to be as fact-driven as possible, here is an excerpt from a blog written by Mary Chisholm, an architectural English historian with many degrees behind her name.

After a long corporate career, she earned a Master’s in Building History at Cambridge University. Her dissertation was on Tudor Gentry Gatehouses in South West England.

With tobacco. . . .smoking was the new, exclusive and fashionable habit. Sir John Hawkins possibly introduced tobacco to England in 1564 but then and for the following couple of decades or so, it was rare and exclusively for the extremely wealthy. In 1578 (Sir Francis) Drake brought back tobacco to England and he showed (Sir Walter) Raleigh how to smoke it using a long-stemmed clay pipe of Native American origin. In 1579 Raleigh staged in Plymouth a demonstration by some of the colonists of inhaling and swallowing smoke. It was a great success.

What Raleigh did was make smoking pipes a new fashion in England by bringing them to Queen Elizabeth’s Court in the 1500-1600s.

July 27, 1586, is the most common date given for the arrival of tobacco in England when it is said Sir Walter Raleigh brought it to England from Virginia. In 1586, reports of the colonists puffing away on their pipes started a craze at Court. It is also historically reported that in 1600 Sir Walter Raleigh tempted Queen Elizabeth I to try smoking.

This became accepted and popular among the population as a whole. By the early 1660s, the habit was commonplace https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Introduction-of-Tobacco-to-England/

And, according to historic accounts, Raleigh, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth, even encouraged the queen to try tobacco in the clay pipe.

This is one of the historical parts the Pundit especially enjoys. When the founding fathers visited a “tippling house” for a wee dram of spiritous drink until the wee hours, they took their clay pipes with them.

Or they simply brought along a clay pipe stem stuffed in a greatcoat pocket. Once at the noisy tippling house, better known today as a pub or more crudely as a bar, they picked up a clay bowl off of a fireplace mantel and attached their clay stem. They filled the bowl with a typical America Virginia leaf and lit up.

And, make no mistake, Virginia was a hotbed of tobacco leaf. Later, other states—notably North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky — joined the tobacco parade.

Sadly, today tobacco farming has fallen on difficult times. The plant is not as prevalent as in the past. Indeed, you will be hard-pressed to find a tobacco auction barn left in Tennessee and other once productive tobacco-producing states.

But in America’s young history, tobacco was a terribly important cash crop in the earliest days of America’s fledgling economy.

Most of the colonies’ tobacco production went to London merchants. Some accounts report that in exceptionally good crop years colonial farmers sent an amazing 500,000 pounds of Virginia tobacco across the Atlantic.

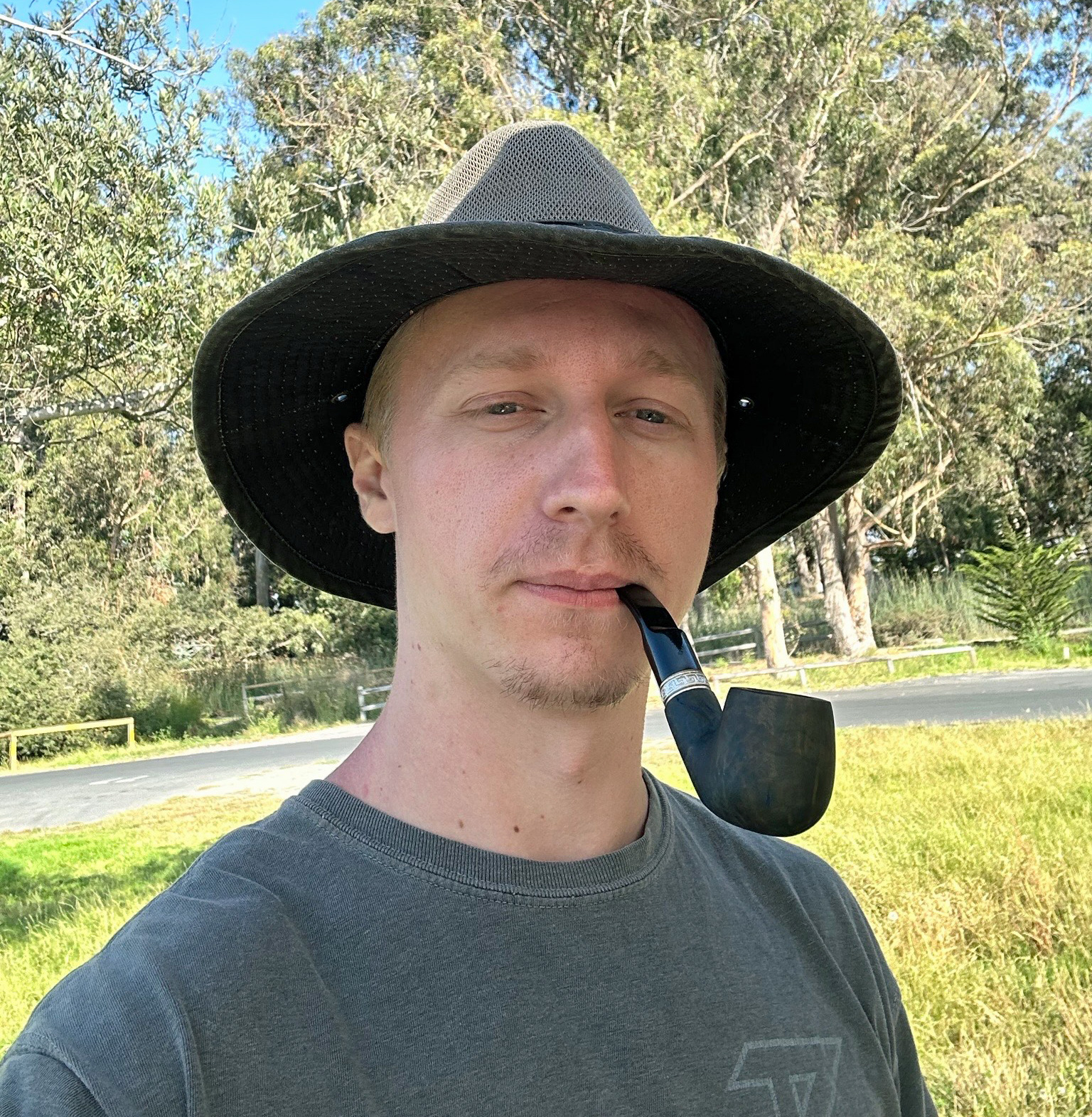

The notion of smoking a clay pipe, once the purview of Native Americans in ceremonial events is just an intriguing thought.

And, yes, the Pundit owns some clay pipes. They require a different smoking technique, which I enjoy. Call it low and slow, like cooking barbecue, Southern-style, doncha know!

Clay is similar to meerschaum, but not as forgiving. You puff like a freight train with a clay pipe, and you will wind up with a fire bed for a tongue.

But, similar to a meer, clay lets the true taste of the tobacco come through if you are a patient puffer. And it allows nicotine to favorably enrich the taste.

Nicotine, by the way, derives its name from Jean Nicot, a French ambassador, according to historical accounts

“In 1560, he learned about the curative properties of tobacco when he was on assignment in Portugal. When he returned to France, he used the New World herb to cure the migraine headaches of Catherine de Medicis. The French became enthusiastic about tobacco, calling it the herbe a tous les maux, the plant against evil, pains, and other bad things. By 1565, the plant was known as nicotaine, (CQ) the basis of its genus name today.”

And now for Mr. Faulkner. If you are a literary inhabitant of the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, Miss., then this is your month to reread a favorite passage.

Several books of the Nobel Prize winner’s novels were set in the fictional county, which corresponds to Lafayette County and the city of Oxford, Miss.

Faulkner roamed the county and the city searching, listening, writing about his “little postage stamp of native soil,” of which, he said he would never exhaust for ideas.

In some quarters around Oxford, Faulkner was known as “count no count.” But “Mr. Bill” was also a popular moniker as well.

At least “count no count” is something I picked up one day while roving around the Square at Oxford, stopping in stores and shops to chat with folks about their famous author.

Faulkner was born in 1897 and died July 6, 1962, at the youngish age of 65.

I also managed to wrangle a visit to Rowan Oak, the 1840s farm home outside of Oxford known for its winding drive shaded by ancient cedar trees.

Faulkner purchased the house and farm in the 1930s and then began repairing it. As I wandered the rooms, I was just stunned when I came to the author’s bedroom and study.

There on the walls of the room he had hand-written the plot outline for the novel, The Fable, which won the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award in 1954.

Of course, Faulkner was rarely seen without a pipe in hand. He was fond of Dunhill’s 965 blend and when he couldn’t get that, I was told he enjoyed Sir Walter Raleigh. Ah, yes, that historical umbilical cord, eh!

Indeed, if my memory serves, there was an empty tin of Sir Walter Raleigh or Prince Albert in a tweed jacket hanging on a wooden peg in a hallway of the home.

If you want an excellent bio on William Cuthbert Faulkner, read Chuck Stanion’s Sept. 11, 2020, column in SmokingPipes.com Pipe Line.

And now my dear friends of the briar, as your pipe pundit concludes our chat today, I leave you with one of my favorite Faulkner quotes:

The past is never dead. It’s not even past—from Requiem for a Nun, 1951.

[White clay pipes are not only smooth smoking instruments, but they also connect America with its early history.] (Photo by Fred Brown)

Fred Brown's Pipe Smoking lifestyle meanderings for July 2021

I enjoyed that, thank you. Now where do I get one of those cool tobacco cuts posters? Cheers!

SmokingPipes.com

Excellent read. You are like bacon. No matter how much I eat, I want more.