By Fred Brown

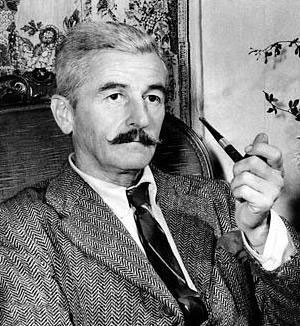

Most biographers agree that William Faulkner and his father never got along, but one particularly nasty argument demonstrates the deep-rooted animosity between the two men – and it was over a pipe.

One night after supper, the family headed to the front porch to relax and tell stories, as was customary in the Deep South. Faulkner’s father, Murry Cuthbert, a cigar smoker, mentioned that he had heard that William had begun to smoke. Faulkner confessed that, yes, he had indeed become a smoker, and he took out his pipe to prove it.

But Murry then handed his son a cigar which Faulkner promptly broke in two, putting half in his coat pocket. He then unraveled the other half and stuffed it into his pipe. His father never offered his son tobacco again.

William Faulkner, one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, continued to smoke a pipe for the rest of his life, and most old photographs taken of him show him with a pipe, confirming his use of tobacco.

His favorite tobaccos were My Mixture 965, in the fancy tin with broad red letters, A10528 by Dunhill, and Prince Albert when he was out of the others. Even years after his death, when his home at Rowan Oak had been turned into a museum, curators found cans of Prince Albert in the closets.

Efforts to find out from Dunhill the origin and commercial name of A10528 were not successful.

Photographs also indicate that Faulkner smoked Dunhill pipes, preferring straight billiards. Even today, Dunhill continues to make a shell billiard with a silver band, about a Group 3, that looks very similar to the one Faulkner smoked.

Faulkner constantly had a pipe going or about to be lit-even in the classroom, a practice permitted in the late 1950s when he was a writer-in-residence at the University of Virginia. Many photos show him at UVA either holding a pipe or smoking it. He also smoked freely during his brief tenure at West Point. In fact, the Special Collections Library at UVA still includes two of Faulkner’s Dunhill pipes, both straight billiards of about Group 3 size.

In his masterful two-volume work on Faulkner biographer Joseph Blotner wrote: “. . . He had placed his first order for pipe-tobacco mixture A10528 with the Manhattan store of Alfred Dunhill of London. Originally made up for an old customer, this blend had caught on by word of mouth until it had become one of Dunhill’s popular standard mixtures. To a burley foundation were added Turkish and Latakia for the flavor base; when finished it was a blend of thirteen different tobaccos which sold for six dollars a pound. Faulkner would use other tobaccos, sometimes blending a mixture himself, but for the rest of his life the Dunhill blend would be his staple. One of his friends, entering a room that Faulkner had left, claimed that could tell Faulkner had been there by the strong, rich, heavy aroma.”

His pleasure in smoking was evident as he took a wooden match from a box held in a metal rectangle bearing RAF wings, then pushed the diminishing tobacco down into the briar or corncob, and relighting it until he had tapped out the last fine gray ash. “He was a constant smoker with a pipe almost always in hand except for mealtime and drinktime. . . . he was a man who loved tobacco as he did whiskey and horses,” wrote author Jay Parini of Faulkner.

Even today, Faulkner’s shadow continues to fall broadly across the southern literary landscape. Many of his 19 novels and short stories (a precise number is not known), essays, plays and movie scripts tell of the failed Old South and are based on stories he heard as a child, especially those about the exploits of his great-grandfather, Colonel William Clark Falkner, who spelled the family name without the letter “u”.

Not only did the old colonel become Faulkner’s prototype for the wealthy plantation owner at the start of the Civil War, his demeanor and his adventurous history made him an absorbing archetype for the period. He was a goateed veteran of both the Mexican and Civil Wars and a controversial figure who was known to be socially distant and unfriendly. A physical wound made him even more intriguing: he was missing the last three fingers on his left hand as the result of a Mexican War injury.

The Old Colonel, as his family knew him, was the model for Colonel John Sartoris in Flags in the Dust, rewritten as Sartoris, and The Unvanquished. He also served as a muse in many other ways for the great-grandson he never knew. Joseph Blotner also says in Faulkner’s official biography that the Old Colonel was most likely a “substantial” model for the fictional Colonel John Sartoris, the intriguing Rebel commander who eluded the federals in northern Mississippi.

In addition, fascination with his family’s past started Faulkner on a lifelong interest in genealogy and many scholars believe that his entire career was in response to the Old Colonel in one way or the other, including the 1930 purchase of his antebellum house at Rowan Oak in Oxford, Miss., formerly known as the Bailey Place. Today it is owned by the University of Mississippi and maintained as a Faulkner museum.

|

|

Though Faulkner’s grandfather and his uncle, John Wesley Thompson Falkner, were prominent Oxford bankers, William Faulkner’s father, Murry Cuthbert, never had the kind of success of his forebears had enjoyed. Faulkner, however, was a seed from the old stock. He got the gene from the Old Colonel, who loved not only to tell stories, but also to write them as well. In 1889, his novel, The White Rose of Memphis, became an instant best-seller. According to Blotner, although criticism of the novel was generally favorable, some 20th century critics have seen in the book “a latent level of psychological aberrations and incest motifs which prefigures similar interests in the work of the colonel’s great-grandson.”

It was as if the old man lived on through the great-grandson, who became the fourth American to win the Nobel Prize for literature. Faulkner also won a Pulitzer Prize, and in doing so, gobbled up so much Southern literary real estate that writers who followed him had to scramble to find their own voices and universes.

Although he was born in New Albany, Mississippi, Sept. 25, 1897, eight years after W. C.’s death, Faulkner got to know his great-grandfather through the wild and wooly stories told to him by his great-grandmother, Holland Pearce, who had married the colonel on July 9, 1847, in Knoxville, Tenn.

Many scholars believe that for Faulkner, as for many southern young men born just before the turn of the 20th century, there was a sense that monumental events had happened in the past and they had missed it.

The “Lost Cause” generation mourned the loss of that exciting sense of adventure, but in Faulkner’s case, the involvement of his family heritage in the rise and fall of the South made it even more poignant. It was not only a physical but also a psychic loss as well. The South lost hundreds of thousands of young men in the war as well as hundreds of thousands of acres of land, towns and small communities in the conflict. The scar of the Civil War was an indelible gash that has never quite healed.

As a storyteller, Faulkner inherited a tremendous wealth of information from other family members, local Civil War veterans, and ex-slaves. Not only did he possess a colossal memory, but he was also a great listener, and he soaked up information in detail. Much of it came from his old aunts, who never accepted the fall of the South, were still angry, and never stopped complaining about their losses and consequently provided unending information about the great conflict.

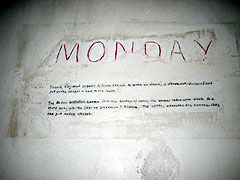

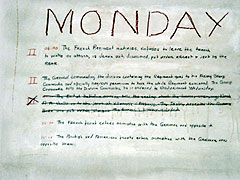

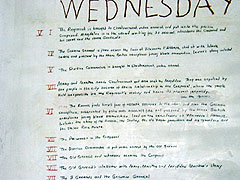

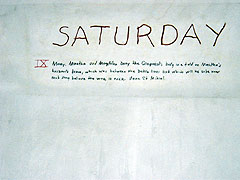

And in a Rowan Oak bedroom that Faulkner turned into an office, the handwriting is literally on the wall. There, scrawled on the white plaster, Faulkner outlined his novel, A Fable, which won the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in 1955.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

In the best of his books – The Sound and the Fury, As I Lay Dying, Light in August, Absalom, Absalom, The Hamlet, and Go Down Moses – Faulkner tried to analyze the war and the South, as well as to assess the tremendous physical and psychological devastation of its people.

Most biographers agree that William Faulkner thought of little else in his life beyond becoming a writer. As early as the third grade, he announced that he was going to be a writer like his great-grandfather.

In many ways Faulkner’s literary output is one great requiem for the Old South. Whether he composed at a desk or on the wall, he wrote the story of the South as it had never been written before or since.

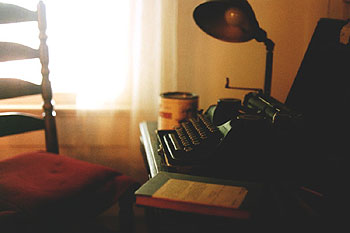

And, most of his stories, even poems, were written with a pipe either beside his old typewriter or between his teeth. A modern photo of his desk shows the Remington typewriter and a can of My Mixture.

“My own experience,” he once said, “has been that the tools I need for my trade are paper, tobacco, food, and a little whisky.”

William Faulkner Related Links

Faulkner Memorabilia at Virginia.edu

Becoming Faulkner: the art and life of William Faulkner

CNN Southern Living

Fred Brown is a Retired Senior writer for the Knoxville News Sentinel and was a working journalist for 46 years before retiring in 2008. He lives in Knoxville, TN., where he continues to freelance. Fred Brown is a Retired Senior writer for the Knoxville News Sentinel and was a working journalist for 46 years before retiring in 2008. He lives in Knoxville, TN., where he continues to freelance. |

All Photos, with the exception of the first two, Courtesy Fred Brown, Copyright 2011

Nicely done, great article. Thanks!

Great article!

Faulkner remains one of America’s seminal literary figures of the 20th Century. One thing often over looked on the Faulkner resume is the screenwriting that he did. His most notable screenwriting efforts were for “To Have and Have Not” and “The Big Sleep”. Both of these major films were directed by Howard Hawks and starred Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.