Fred Brown

Even before the Big Bang theory of the universe came into vogue, Edwin Hubble talked of "nebulae" swirling at great distances from Earth, with stars so far away, they appeared as thin mist in his telescope. The red glint in faint light wavelengths gave him the notion of a powerful force moving at tremendous speeds and that the more distant the nebulae, the faster they moved away from Earth.

Edwin Powell Hubble was a sky walker, a cruiser of far-off galaxies whose brilliance and curiosity led to his discovery of the fundamental structure of something as large as the universe.

At the time he arrived at this startling idea, he was a brilliant 30-something, explaining mysteries of the universe and how it works. He called it, naturally, Hubble’s Law, which clarified the rate the universe expanded in all directions.

In an environment of academic jealousies (that seemed almost as large as the universe itself), Hubble assumed the risky position of declaring that those big spirals he glimpsed were hurtling away from the Earth at great speeds, that in fact the universe was not static, but a mass moving at warp velocity. With this discovery, Edwin Hubble altered the thinking of what the universe was, and where it was going. Not for nothing is he called the Father of Cosmology.

And when he talked in his authoritative voice, one of his students said it was like hearing God speak.

And, yes, Edwin P. Hubble, never a modest man, would probably have agreed.

Born on the plains of Missouri, Edwin Hubble soared to great heights in a scientific world, making discoveries that altered the theories of even the greatest mind in the world, Albert Einstein. In fact, Hubble’s Law of the structure of the universe forced Einstein to reexamine his own math, relatively speaking, on all that Earth and space discoveries with which Einstein wrinkled the heavens and warped time.

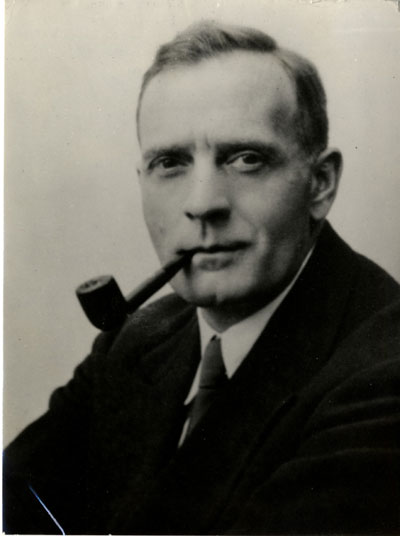

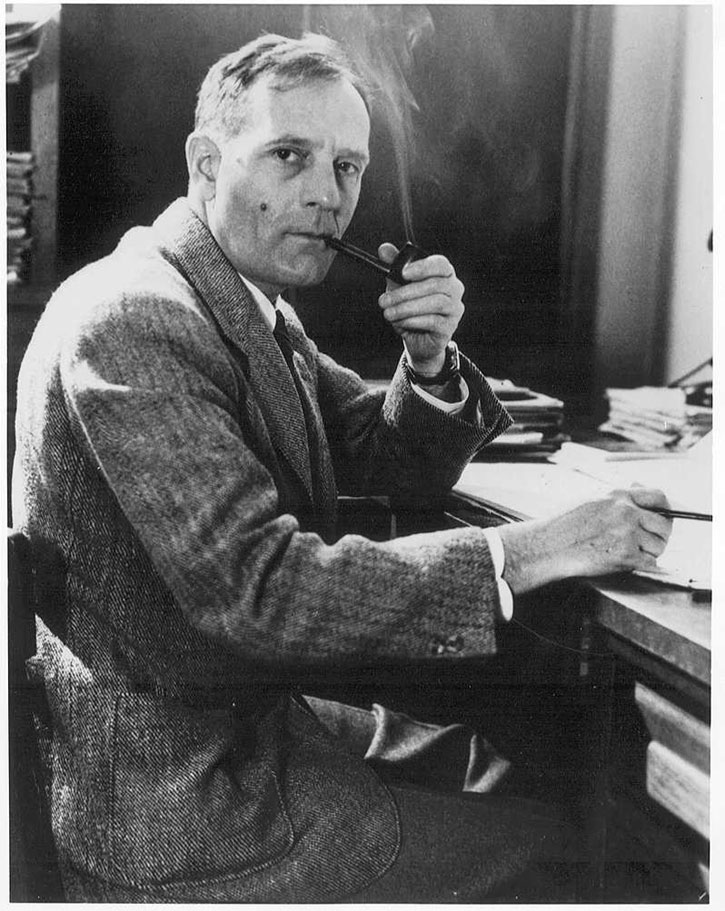

Hubble was not only a brainy chap, but he was also a confirmed and persistent pipe smoker. Inveterate, you might say. A man of briars, Hubble was rarely seen without a billiard. Like Einstein, he carried his pipe with him everywhere he went, and both great scientists enjoyed their cigars in between pipe bowls.

For the most part, Hubble smoked Dunhill pipes. There is a reason for his Dunhill preference, but that bit of his past begins at Hubble’s beginning.

Edwin Hubble was born in Marshfield, Mo., in 1889, the third of seven children. His father, John, was an attorney, but earned his living in the family insurance business. Work came naturally for John and all the Hubbles, who not only assisted their father, Martin Hubble, in the insurance business, but also labored on a 640-acre family apple farm in Marshfield, a land of rolling countryside, prairie and timber.

John Hubble married Virginia Lee "Jennie" James in Marshfield Aug. 10, 1884. Jennie’s family had deep Southern roots. Her father, Dr. William James, was born in Blount County, Tenn., grandson of Scotch-Irish slave owners. Blount County, next door to Knoxville, Tenn., lies in the vast Blue Ridge Mountain Range known today as the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Edwin’s father, John Hubble, was Baptist, strict, stern, demanding, and often at odds with his son, who always seemed to have his head in the stars. John’s one unlikely vice was the love of pipes and cigars, a trait that he passed on to his son. John would often blow smoke rings, and his seven children made a game of trying to catch them. Later, Edwin Hubble would blow smoke rings around the world.

Edwin’s father, John Hubble, was Baptist, strict, stern, demanding, and often at odds with his son, who always seemed to have his head in the stars. John’s one unlikely vice was the love of pipes and cigars, a trait that he passed on to his son. John would often blow smoke rings, and his seven children made a game of trying to catch them. Later, Edwin Hubble would blow smoke rings around the world.

Edwin was more like his grandfather, Martin, who also smoked a pipe, loved to tell stories and was something of a character. The grandson later turned the art of storytelling into a kind of cottage industry for reputation-making events, such as the story of his attempting to line up a bout to fight Jack Johnson, boxing’s heavyweight champion of the world at the time. He also claimed to have battled George Carpentier, the French heavyweight, to a draw. These are likely exaggerations that a grandfather would enjoy, but good ones nonetheless.

However, the tall (six feet-plus) handsome Edwin was a stalwart athlete who played basketball, ran track and boxed in high school and college. He was a top athlete, always a steady contender for first place, and record-setting achievements. He was extremely competitive, a quality that was a hallmark of his character.

Though highly intelligent, Edwin was somewhat lackadaisical about his studies, until the University of Chicago accepted him on an academic scholarship. His father insisted that Edwin should get a law degree, but the stargazer had other ideas.

He wanted to study astronomy and he wanted to win a Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford, England. Thus, he entered the University of Chicago in 1906, and filled his academic schedule with math, physics and science courses as well as the prerequisites for law.

In 1910, he was chosen for the Rhodes scholarship in Illinois (the family had moved to the state for John’s insurance business). This meant that Edwin Hubble would go to one of Oxford’s esteemed colleges for three years, taking the course of his choosing.

His father wanted his son’s career to be law; and though the headstrong Edwin acquiesced to his father’s wishes, he also studied math, astronomy and later, English literature.

Over time, Oxford and the English countryside changed his sartorial style, and he affected a cane and a long black English cape. England had won his heart forever.

English life suited him immensely. And he even made the most of the $1,500 yearly stipend to travel Europe—by bicycle. He toured Germany before World War I, earned a couple of fencing scars to prove his honor and manhood, and recognized that if war were to break out with England and France, it would be a bloody affair. Germans, he said, made good soldiers.

Edwin Hubble slid easily into the role of an Anglophile, adopting English customs, even down to changing his speech patterns. He became an Englishman in all but birthplace, so it seems, even learning how to make a proper cup of tea. He adopted tweeds, plus fours, knickers, and, of course, British pipes, which held a prominent place on the Spartan desk in his dormitory room at Queen’s College.

Living in England, it seemed only natural to prefer English briars. At the time, Dunhill was becoming the world’s finest pipe maker, having perfected the shape and a curing process that continues in much the same way today.

When World War I began to embroil America, Edwin was already home from his Oxford days and living in Louisville, Ky., with his family. He was teaching in high school, but wanted desperately to work in astronomy, hunting stars. His father had died in 1913, just before Edwin finished at Queens College. His death both liberated and saddened Edwin, who had never really come to terms with his father’s expectations of him, but now he was free to roam the stars.

In 1915, he finally landed his dream opportunity at Chicago University’s Yerkes Observatory, where he worked viewing the night skies. Photos of Hubble at the Yerkes telescope usually show him with a pipe in his mouth.

In 1915, he finally landed his dream opportunity at Chicago University’s Yerkes Observatory, where he worked viewing the night skies. Photos of Hubble at the Yerkes telescope usually show him with a pipe in his mouth.

Mount Wilson Observatory, near Pasadena, Calif., promised him a post when he finished his Ph. D. dissertation. However, World War I intervened and when the United States entered the conflict, he volunteered and rose quickly from private to captain to major. He didn’t make it overseas until July 1918 with the 82nd Division, known as the "Black Hawks."

By the time he arrived in France in September, the war had only a couple of months to go before the Armistice. Although Hubble claimed to be in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, his war record is somewhat cloudy, and to this day subject to his several reputation-enhancing stories that cannot be qualitatively verified.

The 86th, however, never saw combat.

Nevertheless, he was promoted to the rank of major and was at Meuse-Argonne. He always maintained that he was a trench infantry officer and was knocked senseless by a bomb explosion. Years later, he returned to the front with his wife, Grace Burke Leib, daughter of an influential Los Angeles banker. Grace had been married to Earl Leib, a prominent geologist, who was killed in a mining accident. Hubble and Grace married February 1924 in California.

In 1926, the couple built their dream home, an Italian style palazzo, in San Marino, Calif., near Pasadena and the Mount Wilson Observatory.

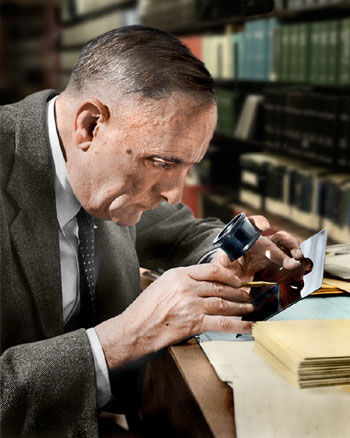

For Hubble, the post-World War I years were as bright as the firmaments he studied and photographed with the large telescopes that were just emerging through advancing technology. His first post at Yerkes led to the most prestigious job of his career at the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory, founded in 1904 by George Ellery Hale and was home to the magnificent 100-inch telescope that offered stunning views of the deep beyond.

The observatory still stands north of downtown Los Angeles on the 5,710-foot Mount Wilson. In 2009, a massive wildfire, named the Station Fire, consumed large tracts of the Angeles National Forest in the San Gabriel Mountains northwest of Los Angeles. But although the fire threatened the renowned research observatory where Hubble made most of his important discoveries, it did not damage it.

Beginning in 1919 at Mount Wilson, Hubble dazzled the science world with his work on proving the existence of "island universes" in space. These were independent galaxies larger than the Milky Way, which was a startling discovery at the time, a discovery that showed that the Earth was not the center of the universe, but was instead only a tiny part of the vastness.

There he also met and feted Einstein who was visiting America for the first time in late 1931 and early 1932. It was during this visit that the great thinker realized that if Hubble were right, he was wrong. Heady stuff.

Though Hubble was never as popular as Einstein was in that time just before World War II, he became a darling of the Hollywood social set as well as some of the world’s leading writers and thinkers. He enjoyed being around Hollywood’s beautiful people and was a talented speaker who was in high demand.

His home, whose view included the San Gabriel Valley, was a constant party scene with hordes of visiting movie stars.

Through all of this attention, Hubble was seldom without his pipe. His tobacco was specially ordered from the London Pipe Shop of Los Angeles, a tobacconist that opened in 1932, according to California court documents, but the shop is no longer in operation.

One of Hubble’s favorite party tricks was to strike a wooden match, flip it into the air, catch it on its wooden end and then light his pipe.

His biographer, the historian Gale E. Christianson, writes that Hubble’s office at the San Marino home was soon stained by tobacco smoke. "Its polished oak floor, thickly plastered walls, and barreled ceiling. . . .would soon become discolored from the rising smoke of his many pipes. . . ."

By the time of his death in 1953 from a blood clot on the brain, a little over one month before his 65th birthday, he had amassed a sizeable pipe collection. What has happened to that collection is anyone’s guess. Hubble was a public man but a private scientist. His wife burned all of his papers and other important documents, even their letters, after her husband’s demise.

Some of those Dunhill pipes would be pre-World War I vintage and quite valuable now, and since he and Grace had no children, the pipe collection is more than likely lost forever.

Among his many scientific awards was the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1940. He never won the Nobel, but because of his efforts, astronomers today can receive the honor. However, his lasting legacy is the Hubble Space Telescope, launched by NASA in 1990.

And though its original optics were off, three years later the telescope was repaired and has since returned majestic, spectacular photos of stars being born, dying, black holes at the center of galaxies, collision of galaxies, and supernova explosions, that suggest the expansion of the universe is accelerating.

Edwin Powell Hubble’s wife scattered his ashes to the wind, and perhaps he now lives among the stars he explored and so loved throughout his lifetime.

Fred Brown is a Retired Senior writer for the Knoxville News Sentinel and was a working journalist for 46 years before retiring in 2008. He lives in Knoxville, TN., where he continues to freelance. Fred Brown is a Retired Senior writer for the Knoxville News Sentinel and was a working journalist for 46 years before retiring in 2008. He lives in Knoxville, TN., where he continues to freelance. |

Excellent article! It’s no surprise that a man so brilliant was a pipe smoker though.

-J

Wonderful and highly informative article!

Many thanks!

This is yet one more in a series of edifying articles outlining the lives of famous pipe smokers. Thanks for a job well done; and for the pix that accompany the bio.

Nice article, but I suspect the part about Einstein is incorrect. Einstein completed his great work prior to 1920 and to this date there has been no significant revision of any of it. Hubble’s masterpiece of discovering the expanding universe wasn’t until the late 20’s. I guess upon reflection that this could be referencing Einstein’s use of a “cosmological constant” in one of his field equations which has since turned out to be more right than wrong.

An interesting point of Hubble’s life is the reason he never won a Nobel Prize. During his lifetime the Nobel Prize for physics could not be won for work in astronomy. Hubble campaigned for years to get the Nobel Committee to consider astronomy as a part of physics so astronomers (particularly himself) could win the Nobel Prize. By the time the committee got around to doing this and preparing themselves to award Hubble the prize he died. The Nobel Prize can only be granted to the living. It’s okay to die once they announce your name, so you don’t have to necessarily make it to Oslo to formally accept the award.

A great read, I love this series. If anything it’s a great introduction to the subjects, and an invitation to pursue more reading on my own.

Please never forget that General MacArthur and Einstein were pipe smokers, as was Carl Jung.