Years ago a friend, knowing that I collect GBD pipes and related ephemera, gave me a lovely 7oz tin of GBD Black Cavendish Mixture, manufactured for them by Sobranie House. I’d never seen this tobacco, so it was certainly a welcome addition to the collection.

The tin had been opened for some unknown length of time when he’d acquired it, and while the label and exterior of the tin were in fairly good shape, there was a lot of oxidation internally, and the contents had long since become drier than bones in the desert. I was reluctant to try it in that state, so it has remained displayed on a shelf until recently, when the curious chimp on my shoulder finally got the better of me. I grabbed the tin from the shelf, and gave it the once-over.

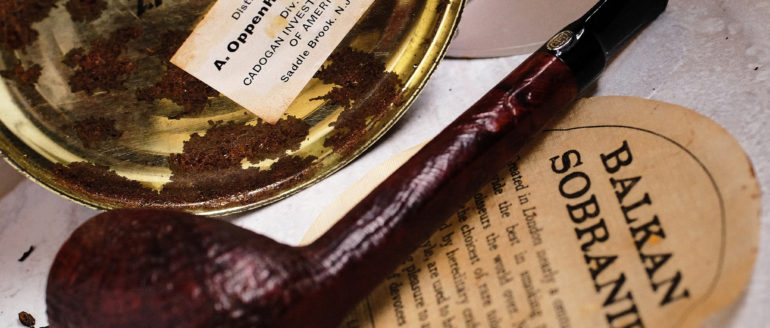

The plastic overcap is discolored from age, but still perfectly pliable, and it pulled away without incident. A small paper label on the enclosed aluminum pull-top indicates that the tobacco was “Matured In Rum,” so that spirit was definitely used in some part of the process. A translucent paper disc under the pulltop reveals the pedigree of the tobacco’s Sobranie manufacture.

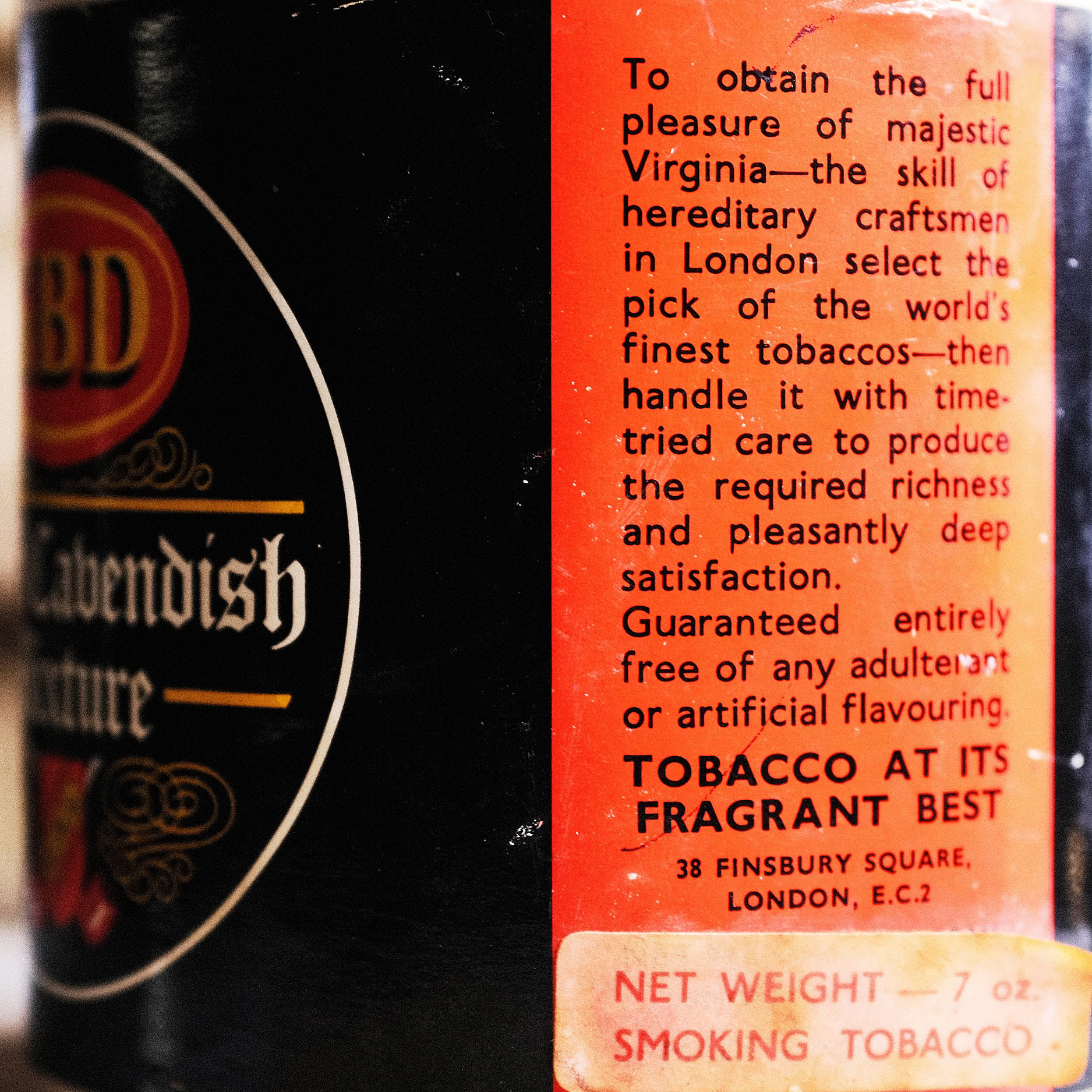

The back label reads, “To obtain the full pleasure of majestic Virginia-the skill of hereditary craftsmen in London select the pick of the world’s finest tobaccos-then handle it with time tried care to produce the required richness and pleasantly deep satisfaction. Guaranteed entirely free of any adulterant or artificial flavouring. TOBACCO AT ITS FRAGRANT BEST” Clearly rum is considered neither an adulterant nor artificial. The original printed 200g weight declaration on the label had been covered by a paper sticker at import showing a net weight of 7oz, indicating this tin to likely be from the late 1970s or early 1980s.

But, what about the tobacco? Black Cavendish means different things to different manufacturers. In the US, it’s a term usually applied to cut leaf that has been heavily sugared and steamed or roasted for hours at a relatively high temperature to darken it and partially oxidize and caramelize the sugars. Usually, additional flavoring agents, commonly vanilla, are applied after the heating process.

But, as this was a Sobranie of London product, it was more likely moistened, hot-pressed in steam jacketed presses and held under pressure for days or weeks before being tumbled in a heated conditioning drum to return the leaf to ribbon form at the correct moisture content. My guess is that the rum was applied before or during the cavendishing process.

Examining the contents revealed that much of the rust had fallen away from the sides of the tin, both as large and small flakes, and as countless tinier particles too small to see, let alone fish out with tweezers, so the first order of business was to find a way to get rid of as much of it as possible. Since rust is at least somewhat paramagnetic, a bit of grade school science came to the rescue. I spread the tobacco out in small quantities in a shallow bowl, picked out the larger rust flakes, and then carefully raked through it with a strong magnet, removing most of the smaller particles.

The tobacco was then carefully sifted to remove a large amount of dust, and hopefully whatever tiny rust particles remained. At this point, a little over 110g of desiccated ribbons remained, so all that was left was to carefully condition the tobacco back to a smokable 12-13% moisture.

Rehydrating tobacco this dry and frangible can be tricky business. It has to be done very delicately to avoid breaking the ribbons up even further, and in measured amounts to prevent over-moistening. In a dry environment, tobacco can give up its water very quickly, but it is much slower to absorb it, so just spraying it with water is ill-advised. My normal method would be to put it in a bowl covered with a damp towel and let the leaf take up moisture gradually; this can take days of monitoring, rewetting the towel as needed, and waiting. Feeling a bit impatient, I chose instead to put a carefully measured amount of water in a small atomizer, and began delicately misting and turning the ribbons until they were evenly coated. Then, it could be safely transferred to a jar and sealed until the leaf had time to take up the added water, a process that can take several hours.

After an hour or so of messing about with the stuff, and a few more hours of impatient waiting, it was time to give it a try, of course, in a GBD pipe. I picked a sandblasted Sablée lovat that has always performed its best with virginias, and gave it a go. The verdict?

It is delicious. Despite the years of abuse the tobacco had suffered, hints of rum punctuate a deep, rich virginia goodness. Background notes of stewed figs are present, and an earthy, almost malty sweetness, with an elusive tartness that keeps the palate interested. The room note is subtle and engaging, not at all cloying. There’s no way to know how far this rehydrated tobacco deviates from what it would be like had it never endured such abuses, but if I’m ever fortunate enough to find a sealed tin of this stuff, I’ll sure as heck give it a go to find out.

Photos by G.L. Pease

A great GBD find! I love collecting ephemera almost as much as I enjoy collecting pipes. I was gifted a few tins of dried out tobaccos at the TX Pipe Show last fall that I spritzed awake with distilled water over a few days. I’ve had them slowly dehydrating in bags with Bovida packs since November. I sampled a couple last week and they tasted fine. I’ll probably jar them up soon.