E. Roberts

In the first part of this series, A Brief History of Two Leaves: Tea & Tobacco, we took a look at the remarkable parallels in the early histories of tea and tobacco—plants springing out of the ground from falling body parts, a close association with spirits and the divine, a sense of ritual. In an age before the modern chemical pharmacopeia, they were both also considered primarily medicinal herbs before their more common recreational uses superceded that.

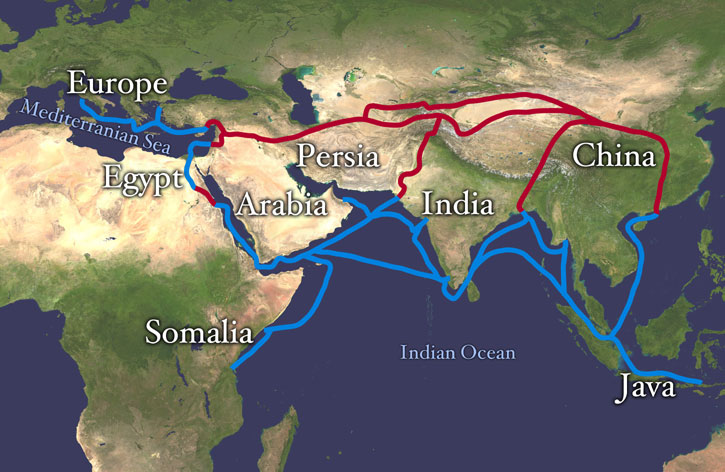

Appetites for the exotic, be it spices or silver, demanded faster exchange over the great distances between Europe and the Far East. Thus, it is in the Age of Discovery—that period of maritime exploration and expansion by the European powers in the 16th and 17th centuries—that tea and tobacco finally make their way around the globe. Wherever they are introduced, they are incorporated into the local cultures and quickly segue from medicines to exotic luxury goods to vital commodities. With this growing power, they often changed the face of industry. Tea had been filtering slowly westward for centuries overland via the Silk Road, spreading its roots through Russia, India, and Arabia along with the cargo of spices and the textiles for which the route was named. As it changed hands it also changed languages, and the name of the plant was transmuted from ch’a to chai to tay to tee as it moved through Persia and Araby, yet it always retained its phonic sibilance. With this peregrination it also moved slowly out of the realm of the aristocracy to the common people, particularly finding favor with monks and missionaries. It was a common beverage to be had in Mecca, for instance, as pilgrims observant of the Islamist temperance found it a pleasing and religiously acceptable stimulant.

The "Silk Road"

Over time the Middle Eastern cultures developed their own particular rituals and customary preparations associated with tea that differed from its Chinese roots. For example, in Morocco, green tea found its local gastronomical counterpart in mint, and its preparation is traditionally a masculine role. In Turkey, conversely, the tea is strong, black and sweet, and the preparations reserved for women. In nearly all cultures, though, tea became conduit for talk and trade, negotiation and contemplation—walk into any bazaar from the Khan el-Khalili in Cairo to Senado Square in Macau and you’ll likely be entreated to haggle prices over a cup of tea, as were visitors four hundred years ago. This peculiar affinity for commerce is a recurring theme in tea’s history.

As the 16th century dawned, the oceans had been transformed from a terrifying, unknown expanse (and possibly the edge of the planet) into the superhighways of the day. The European powers raced to expand their territories and meet the demand for goods from spices to saltpeter. The Americas were "discovered" in the search for a faster route to China, of course, and opened up commercial and colonization opportunities on yet another front. After the initial realization that they had in fact reached a place that was not at all China, the Spanish and Portuguese were more than happy to exploit the vast, new resources they found. Tales of cites made of gold and fountains of eternal youth were more than tantalizing, naturally. The real gold they found would arguably be the humble tobacco plant.

Tobacco benefited greatly from the common sailors’ appetites, and it was on the caravels and galleons of Portugal and Spain, England and the Netherlands that the fragrant weed traveled the globe. In the span of a century, tobacco was seeded from the Mundus Novus, the new world of the Americas, to the entirety of the globe via every port town and harbor along the sea routes. It first traveled eastward to Europe and North Africa with the Portuguese, who dominated the high seas at the time. It followed the first direct voyage from Europe to India with Vasco da Gama in 1498, then further into the Spice Islands and eventually China and Japan. It took root firmly in Spain and Portugal, and was hailed in many early texts as a cure-all medicine, administered in a variety of ways. Occasionally tobacco, like tea before it, also accompanied the travels of holy men. When the Dutch and Portuguese sailors introduced it to ports in Japan, it penetrated the interior of the country with the help of Buddhist monks. It seems they had developed an affinity for the fragrant stimulant, and as well could use the seeds as currency along their travels. The sailors’ connection to tobacco survives intact to this day, with the term "Navy Cut" still being a topic of controversy in the realm of pipe smoking. Latakia leaf is so named after the Syrian port city, and names like Escudo and Borkum Riff perpetuate the mystique of the seafarers.

Tobacco benefited greatly from the common sailors’ appetites, and it was on the caravels and galleons of Portugal and Spain, England and the Netherlands that the fragrant weed traveled the globe. In the span of a century, tobacco was seeded from the Mundus Novus, the new world of the Americas, to the entirety of the globe via every port town and harbor along the sea routes. It first traveled eastward to Europe and North Africa with the Portuguese, who dominated the high seas at the time. It followed the first direct voyage from Europe to India with Vasco da Gama in 1498, then further into the Spice Islands and eventually China and Japan. It took root firmly in Spain and Portugal, and was hailed in many early texts as a cure-all medicine, administered in a variety of ways. Occasionally tobacco, like tea before it, also accompanied the travels of holy men. When the Dutch and Portuguese sailors introduced it to ports in Japan, it penetrated the interior of the country with the help of Buddhist monks. It seems they had developed an affinity for the fragrant stimulant, and as well could use the seeds as currency along their travels. The sailors’ connection to tobacco survives intact to this day, with the term "Navy Cut" still being a topic of controversy in the realm of pipe smoking. Latakia leaf is so named after the Syrian port city, and names like Escudo and Borkum Riff perpetuate the mystique of the seafarers.

It was at the Portuguese court that the French ambassador Jean Nicot de Villemain became acquainted with tobacco in the 1550s. He wrote glowingly of its medicinal properties and eagerly introduced it to his countrymen, even curing the Queen Mother’s headaches with a pinch of snuff and sharing it with the Father Superior of Malta and his monks. It is in his honor that Linnaeus christened the plant Nicotiana tabacum, securing his place in history—though perhaps not to his approval, considering the contemporary climate toward it.

By the turn of the 17th century, tobacco and tea had effectively made their way around the earth from opposite directions, meeting in Europe. It is with the creation of the East India Companies, first by the British in 1599 and then by the Dutch in 1602, that the two plants really begin to flex their muscles. The two East India Company enterprises were consortiums of traders who pooled their resources to secure a monopoly with Southeast Asian territories. What started as a logical extension of hedging the risks associated with sea journeys ballooned into the world’s first mega corporations, the likes of which had not been seen before nor since. Their economic powers soon surpassed simple marketeering to the point where they administered territory through treaty and conquest, had the power and authority to build armies and declare war, and held controlling interest in their respective home governments. The East India Companies dealt in many goods, and tea was at first little more than a curiosity that the royalty and upper class could indulge in, owing to the expense of its journey to Europe. As the ships grew bigger and more numerous continuing into the 18th century, however, the price conversely shrank to the point that commoners would eventually enjoy the beverage as well. Tea soon was served in coffeehouses throughout the Continent and the Isles, and began its shift from a medicinal drink to a more casual and contemplative one. The coffeehouses of the day were very much boys’ clubs for the merchant class, and tea was a perfect accompaniment to conversations of politics and commerce.

Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese wife of Charles II, is actually credited with tea’s meteoric rise to fame in England in the mid-1600s. Cathy was a teetotaler, eschewing wine and spirits in her court in favor of tea (though unfortunately for this narrative, the word "teetotaling" has nothing to do with the drink). Already a popular beverage in the Portuguese court, her example paved the way for tea to be socially acceptable for women and the bourgeoisie. Though it had gained a foothold in the coffeehouses, they were a male-dominated realm; through Catherine’s example it became appropriate for women as well, and once the floodgates were opened they swung wide. Along with the use of a fork at dinner, Catherine had introduced high tea to the world. It had now become firmly ensconced in the European palate, and demand for it grew rapidly over the coming decades. Beginning as a curiosity that ship captains brought back for their personal use, it had bloomed into a commodity of absolute necessity. The East India Companies expanded their colonization in India largely with tea plantations, particularly after the Assamese variety and fermentation techniques became popularized and refined from 1644 onward. This marked a shift from green tea to oolong and black teas. As a measure of its demand, from the mid-1600s to 1700 Britain had imported nearly two hundred thousand pounds of tea; by 1720 it had eclipsed even silk as the primary Company product with over ten million pounds, and by the 1750s over forty million pounds came in legally.

Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese wife of Charles II, is actually credited with tea’s meteoric rise to fame in England in the mid-1600s. Cathy was a teetotaler, eschewing wine and spirits in her court in favor of tea (though unfortunately for this narrative, the word "teetotaling" has nothing to do with the drink). Already a popular beverage in the Portuguese court, her example paved the way for tea to be socially acceptable for women and the bourgeoisie. Though it had gained a foothold in the coffeehouses, they were a male-dominated realm; through Catherine’s example it became appropriate for women as well, and once the floodgates were opened they swung wide. Along with the use of a fork at dinner, Catherine had introduced high tea to the world. It had now become firmly ensconced in the European palate, and demand for it grew rapidly over the coming decades. Beginning as a curiosity that ship captains brought back for their personal use, it had bloomed into a commodity of absolute necessity. The East India Companies expanded their colonization in India largely with tea plantations, particularly after the Assamese variety and fermentation techniques became popularized and refined from 1644 onward. This marked a shift from green tea to oolong and black teas. As a measure of its demand, from the mid-1600s to 1700 Britain had imported nearly two hundred thousand pounds of tea; by 1720 it had eclipsed even silk as the primary Company product with over ten million pounds, and by the 1750s over forty million pounds came in legally.

Tobacco, too, had enjoyed a remarkable rise in popularity and economy during the 1600s. Though it had been transported to the corners of the earth, it was primarily a cash crop in the American colonies. Francis Bacon wrote poetry about it, and the smoke wafted across Europe. Kings James and Philip III tried to outmaneuver each other for supremacy in the European market of New World tobacco, while in the colonies a man could purchase a wife for a couple hundred pounds of the leaf. In fact, tobacco was a primary legal tender for the first 200 years of the American colonies, and lasted longer than gold as a currency standard. The concept of royal monopoly on the transport and taxation of the golden leaf were part and parcel of nation building in this Age of Discovery. Considering its rather gradual dispersal over the course of the 16th century, tobacco use increased exponentially in the 17th century. Perhaps owing to this extreme and growth, attitudes toward tobacco swung drastically both for and against it. In the space of a decade, one Pope condemned its use while another established a cartel for it; one Sultan of Turkey sentenced tobacco users to be executed as infidels, only to have his successor repeal the ban and name it (along with coffee, wine and opium) as one of the four "cushions on the sofa of pleasure". One medical treatise would declare it a panacea while another would decry it as a social poison.

Trade disputes, territorial land grabs and piracy were ripe ingredients for the numerous skirmishes and outright wars over the period from 1500 to 1750. The settlement of the Americas and Far East enterprise had so rapidly accelerated the growth of the European empires and their bourgeoisie that it may seem only natural that the world was in a near-constant state of war for over two hundred and fifty years. The advent of the East India Companies was a natural progression of this attitude of mercantile hegemony. Agricultural surplus is what built our cities and civilizations, and the desire to alter consciousness is innate to the human condition; thus, it is not surprising that these two leaves, by offering a biochemical route to shift consciousness, became the most important cash crops to Europe. To make a social commentary, perhaps it is because these two leaves were both rather acceptable and mild inebriants, and easily transportable, that they became such essential products. Expansion was expensive, and was often paid for by piracy, land-grabbing, coercion, or outright war. The East India Companies’ traffic in tea to the American colonies was crucial for the revenue necessary to finance England’s emerging dominance over her neighbors. The colonists were understandably incensed at this taxation without representation; to briefly encapsulate a complex time in history, the Townshend and Tea Acts culminated in the fabled Boston Tea Party and, ultimately, in the American Revolution. England’s tea and America’s tobacco were now at war.

I do love a cup of hot tea with a pipe, not to mention a piece of hot pecan pie!

Very interesting article on two subjects you obviously adore.

A very interesting article,one of my regular afternoon drinks with with a pipe is cup of Lapsang tea.

Well now, here’s an informative and unexpectedly erudite treatment of two of my favorite vices. Very well done! A bowl of Navy Flake and a cup of Earl Grey seem entirely in order after reading this concisely summarized and nicely composed article. A great read supported by super pix. Thanks!

This was a great article, another reminder of how tobacco changed the world. I enjoy tobacco and tea daily. Thanks for the history, one of my favorite aspects of this website.

Another fantastic article, deeply enjoyed, accompanied by a bowl and a cup. Bravo!

I drink quite a lot of tea, myself. I started with a green tea phase and then branched out into the black teas. I’ve got a couple new teas coming in the post that I’m looking forward to trying. Thanks for your articles! Both have been fascinating, and I look forward to reading more!

Great article!

Thanks!

You know, there ain’t nothing like it. Actually, over this last winter season, I’ve consumed far more tea than coffee–highly unusual for me, as I’m someone with a wee bit of blood in their coffee stream–and have made many little “flavor discoveries” of my own. Being able to slug back a couple gallons of tea over the course of a day is a lot easier on my system, and I’m sure a lot easier on the nerves of those people around me….

I just love this article! Amazing to hear the history of something I enjoy everyday and take for granted where and how it’s popularity came about. Excited to read more!

Great article!

I drank a lot of tea with my tobacco while I was studying abroad in England. Perhaps it’s time to start up again. You sure do make it sound enticing. Many thanks!

incredible article! I love the history of the world via our favorite substances… always fascinating reading. More like this please!

Well studied. After reading your article I was inspired to brew some first flush darjeeling that I had forgotten about. Thank you!

There are FOUR great things in life;

1) Smoking a pipe

2) Good quality tea.

3) 15yr old scotch whisky

4) Medium rare steak

Nice to see this group enjoys at least two of my vices…:-)

Like the meat on the fire just a tad bit longer, and I had to give up the booze, but that is a solid list Barkar

Very nice article—a tea lover here too.

@Barkar — I’d like to place an order for #3 & #4 on that list as well 😀

@Pipemama–Happy Mother’s Day!

@Amy–Rishi Tea has a great FF, it’s one of the things that put them on the tea world map. Check em out!

@Matthew–Me too! I also owe a nod to Malcolm Gladwell in that regard, though he paints a much more vibrant picture with his stories.

@Sculpture–To make tea sound exciting is high praise indeed! hehe

@Lindsey & Mary–why thank you, ladies! I also write for weddings, bar-mitzvahs and wakes!