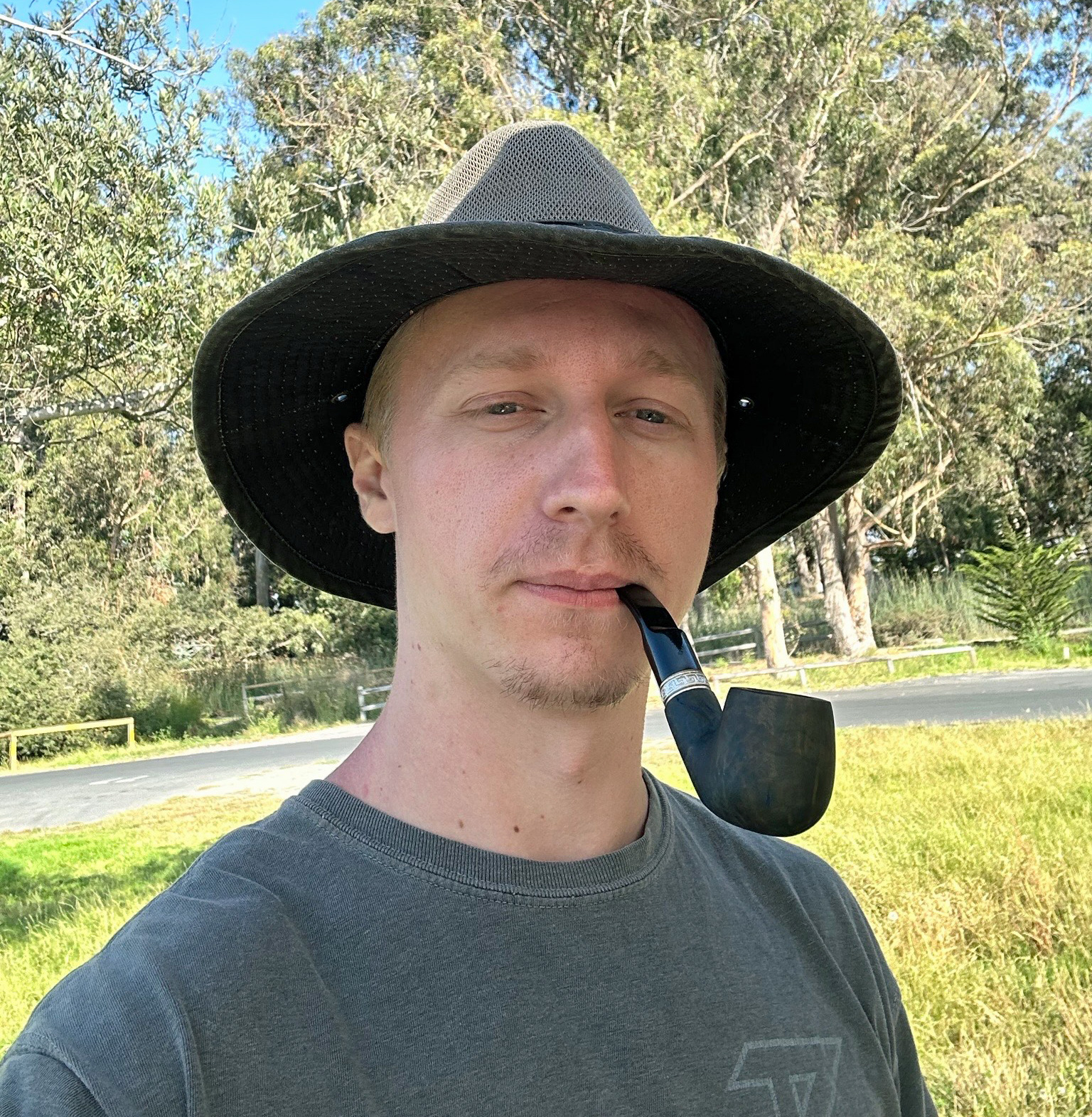

G. L. Pease

Tobacco and terroir. I seem to talk about it a lot, but the myriad manifestations of this "sense of place" continue to fascinate me. The other day, a friend asked me if, given the knowledge of their process and the necessary machinery, I would be able to reproduce the tobaccos created by some of the British blending houses still in existence. I think my answer surprised him.

Tobacco and terroir. I seem to talk about it a lot, but the myriad manifestations of this "sense of place" continue to fascinate me. The other day, a friend asked me if, given the knowledge of their process and the necessary machinery, I would be able to reproduce the tobaccos created by some of the British blending houses still in existence. I think my answer surprised him.

The fact is, even if we knew exactly how they did what they do, even if we had identical machinery, even if we started with identical leaf, the results would be all but guaranteed to be different. Even ignoring the water, which some feel is an important element, there’s the whole issue of that miraculous community of microorganisms that are responsible for the fermentation of the leaf during processing. Since we all rely on the native microflora to do what they do, rather than inoculate tobaccos with specific cultures, there will clearly be differences in tobaccos processed in different parts of the world.

But, there’s something else – something that might even be more important to the finished product. Just as whiskies derive some of their unique signatures from the air that surrounds the oak casks during their long maturation, tobacco will take on the atmosphere of the place in which it’s produced. The stuff is remarkably adept at grabbing aromas from the air around it and hanging onto them up with a death grip. Cigar smokers learn this lesson early; store a cluster of coronas in a place that smells fishy, and the stogies will forever remind you of your mistreatment. Pipe tobacco is no different. Store your highly aromatic Captain Hook in the same shoe box as your pristine pure virginia Tinker Bell, and they’ll each end up taking on some of the other’s personality. It might make Hook a little cheerier, but it’ll transform Tink from prom queen to Carrie. It only makes sense, then, that tobaccos will also pick up the natural aromas of the environment in which it’s made.

Next time you’re puffing on one of your favorite tobaccos from lands afar, see if you might taste just a little of the landscape of where it was born and raised. In fact, join me in a bowl now, and let’s get to the Q&A.

Adam queries: I have a rather odd question for you today concerning the "fifth flavour", umami, as it pertains to pipe-smoking.

Now, I understand the basic science behind the "umami" flavour, whereby free glutamate radicals bind with receptors, causing both other flavours to be enhanced while sending the saliva glands into overdrive; causing a psychosomatic feeling of fullness (and destroying neural connectors in the process). This of course, is achieved in other consumables with the addition of a substance containing an unbound glutamate, such as MSG.

Obviously, a tobacco-blender cannot simply grab the shaker full of MSG crystals and spike the blend; however the free-radical glutamate molecule does not appear naturally in any abundance in any bio-matter I know of – so, how does a blender achieve umami in tobacco?

A: Great food for thought, Adam. Of course, we’re not going to add MSG to our tobaccos. Or are we? A little poking about shows that as early as 1950, tobacco companies, in fact, investigated the addition of MSG in small amounts (0.1-0.2%) to their casing sauces, and there is at least one patent on file discussing this. Why? A capsule look at the pleasure effects of smoking might be beneficial.

Nicotine stimulates the release of dopamine, a powerful neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, in the brain, and while the effect of this direct stimulation is fairly short lived, lasting for only a few minutes, the pleasure effect lingers. Two other neurotransmitters, glutamate and GABA, seem to be the key. Glutamine stimulates increased production of dopamine and "speeds up" neuron activity. Normally, GABA would mediate this activity, slowing down the process in a delicate balancing act. But, apparently, nicotine also inhibits GABA’s function, so while nicotine’s direct effect on dopamine production is brief, the combination of glutamine’s stimulation and the inhibition of GABA’s mediation makes the pleasurable effect last longer. Explaining why the cigarette companies might want to do this is left as an exercise for the reader. But, this has little or nothing to do with umami or taste, and that’s what we, as pipe smokers, are more interested in.

It’s not really clear whether there are umami producing glutamates present in tobacco smoke, though certainly some leaf, latakia and dark-fired Kentucky come to mind, can have a ":meaty" component to their flavor profile. Perique, too, seems to stimulate the "savory" receptors when used in the right proportions in a blend. Since MSG is industrially produced through a process of bacterial fermentation and precipitation, it seems that might be a good place to look for the source of savoriness in some tobaccos.

After harvesting and initial drying, a complex microbial community busy themselves with turning the raw, harsh tasting leaf into the aromatic and tasty product we put in our pipes. It’s possible that glutamate is one of the many additional components synthesized during this phase, resulting in different levels of "savoriness" in various leaf, a long way of saying that while tobacco itself may not produce the umami effect, the delightful little bugs involved in the curing and fermenting may. So while we’re not going to be reaching for the shaker of Ajinomoto any time soon, the tiny creatures that do the real work for us might have their own ideas. Seems like a good research project for someone. Anyone? Beuller? Bueller?

Eric taps on his keyboard thusly: You’ve published many discussions on the mystery of the briar pipe and I’ve submitted a few questions of my own to you periodically the past few years to gain clarification on the wood’s behavior and tendencies. To tell the truth, I’ve been very disappointed and disillusioned with some of my recent briar purchases.

My principal disappointment is with the briar changing its tendencies during the break in period. A couple of examples: I purchased a Radice Aerobillard and the first several smokes produced a wonderful sensitivity to the Virginias I normally smoke. All the subtle nuances were there and I was excited to find a pipe that had that level of sensitivity. I was meticulous with my break-in procedure, smoking only one third bowl for the first dozen or so smokes before progressing to the one half fill mark and smoking half fills for some time before filling the bowl fully. After every smoke I always wipe my bowls out with a piece of paper towel, always clean with Everclear and always rest my pipes. I followed this same procedure with a rather expensive custom pipe I commissioned made from some fantastic Algerian briar that initially smoked so smoothly it seemed pre-broken in. Both pipes reacted the same way during break-in where the more I smoked these pipes the less sensitive they became to the various Virginias I put in them.

Currently, these pipes produce very little nuance and they just seem kind of muddied up because the tobacco flavors are so muted now. It’s gotten to the point where I rarely smoke them because of this "dumbing down" phenomena. To say the least, I’m very disappointed with the performance of these pipes and especially after spending a sizable chunk of change. From past experience and supported by your own musings, I know buying a pipe is a crap shoot, but do pipes that dumb down ever regain their former glory at some point? I haven’t found that they do, although I’ve only been in the hobby about five or six years so I’m not a greybeard in the experience area.

My inclination, though, leads me to believe these pipes will never regain the level of sensitivity they once had when new. I don’t have a huge collection, but out of 25 or 26 pipes two or three are truly outstanding and out of those three one of them smokes only one tobacco outstandingly– and I’ve tried a bunch. That pipe is a Castello and it smokes a Gawith-Hoggarth rope like nothing else, but it falls so completely flat with EVERYTHING else it boggles the mind. Given, my sample size isn’t large, but this metric is not impressive. Again, my limited experience leads me to believe that a pipe will go through the break-in period, settle down to some level of sensitivity or maintain it’s level of sensitivity over a period of a few months and then Bob’s your uncle, that’s it. Will my love for these pipes ever be requited?

A: That’s a tough stem to chew on. Mostly, I’ve had the opposite experience, having an occasional pipe that seemed dull and lifeless suddenly find its way to becoming a stellar smoker. O, the great mystery of briar! A couple of things do come to mind in your particular case. Is it possible that you’re actually doing your pipes a disservice by cleaning them so thoroughly at every smoke? Some old-timers have told me that part of a pipe’s charm is only revealed after a period of time when the built up residues in the shank undergo changes from oxidation. That’s when they begin to deliver "real" flavor.

These pipesters insist that cleaning a pipe too often and too thoroughly actually decreases the pleasure it delivers in the smoke. So, sacrificing my taste buds to science, I tried it out, and found there may be some merit to their argument. A couple of pipes dedicated to virginia tobaccos did, in fact, increase in flavor intensity after a period of repeated smoking and resting with only a very gentle swabbing between bowls, but only up to a point. After a while, the increased richness of the smoke was displaced by that harsh, acrid taste sometimes referred to as "sour pipe," necessitating deep cleaning of their shanks with alcohol and no small number of pipe cleaners. Back to the beginning.

To continue that experiment, I proceeded to smoke the same two pipes in the same manner with the same tobaccos, the only change being that after each smoke, I’d swab the shanks thoroughly with three or four cleaners, folded in half to scrub out the residues. The result? The pipes didn’t become as quite intensely flavorful, but they also remained sweet and clean tasting for a much longer period before needing a deeper cleaning. Seems like a good middle ground.

Finally, I took the drastic approach of an alcohol scrubbing, followed by a couple days rest after every smoke. I can’t say that the pipes really suffered over time from this, but neither did they improve or develop the richness as they did during the first and second part of the experiment. Is there a reasonable explanation for this? Maybe.

When you use alcohol to clean the shank, you’re not only getting rid of the deposited residues, you’re also drying the wood out and opening its pores. Doing this repeatedly might result in more of the delightful flavor components in the smoke stream being absorbed into the surface of the shank rather than being delivered where you want them. In other words, a lot of the tasty stuff might remain in the pipe, resulting in a flatter, disappointing smoke. It’s possible that had I done this part of the experiment with new, unsmoked pipes, I might have had similar results to yours. By never allowing the shanks to "season," you’re getting a clean slate with every bowl, and maybe it’s just too clean. The reason the early smokes were subjectively better could be explained by the fact that the freshly drilled airways are smooth, less porous and somewhat work-hardened by the heat and pressure exerted during the drilling process.

Going further, I cut some stainless steel tubing to perfectly fill the shank of one of the two pipes I used in the experiment. I was a little surprised by the result. The smoke was flavorful and clean and though not as rich as that from a well seasoned pipe, it was still very pleasant, though I did have to use more pipe cleaners during the smoke. Maybe the absorbent shank doesn’t benefit the smoking experience as much as we would like to think it does. And, maybe the greybeards are onto something.

We tend to think that if a clean pipe is good, a pristine one is better, but this little experiment, and the greybeards, seems to suggest otherwise. Try smoking the pipes for a while with a less aggressive cleaning regimen, and see if they don’t come round; my guess is that they will, and that your story will have a happy ending. Please, let us know how it goes.

Kevin pens: Does the color of a tobacco reveal anything specific about its flavor or taste characteristics?

A: Yes, and no. The color of the finished leaf is determined by a variety of factors: the particular cultivar, the growing conditions, where on the plant the leaf was grown, and how it was treated after harvesting. Think about some common very dark tobaccos: black cavendish, perique, dark-fired Kentucky and latakia. They look similar to one another, but couldn’t be farther apart in the way they taste.

At the other end of the color palette, brights are cured quickly to retain their sugar, which also "sets" their golden hue. But, these same leaves can then be fermented, darkening them considerably. Or, they can be heated through steaming or stoving, ultimately resulting in a tobacco that is deep red or even nearly black. This tobacco will have a very different flavor and aroma than a tobacco that is darker when harvested, though it might look very similar.

Further, oxidation over time, the result of aging, and the influence of the other tobaccos in a blend will alter the appearance of the component leaf, sometimes dramatically. So, while the color of the leaf can indicate a great deal at the time it’s harvested, by the time it’s in a tin, all bets are off. There are dark tobaccos that are very mild, and lighter tobaccos that are quite strong. You can’t always judge a book by its cover…

From Jamal: What do you think of the smoking qualities of the reverse calabash system and how does it compare to the real calabash?

Also, a renowned maitre piper (Jean-Nicolas) in Lyon, France told me that Olivewood pipes will eventually burn out (probably in decades), that he doesn’t see any advantage in its smoking qualities and that it’s heavier than briar. What’s your take on the issue?

A: For my thoughts on the so-called reverse calabash (I still don’t understand how it’s "reversed"), have a look at my discussion of the Radice/NeatPipes AeroBilliard that appeared in last month’s Out of the Ashes column. It’s a sample of one, but overall, I like the idea. It’s hard to compare it with a conventional calabash for a couple of reasons. The traditional pipe uses a meerschaum bowl, which has very different smoking characteristics from briar, and the size of the chamber under the bowl is significantly larger in the gourd type. Both of these factors would make quite a difference in both the flavor and the smoking dynamics of the pipe, so it would be a sort of apples to oranges comparison; not nearly as useful as apples to billiards.

As for olive wood, I see no reason for a properly cared for pipe to burn out. It’s been shown that briar is remarkably fire retardant, able to withstand direct candle-flame heat for over two minutes before beginning to smolder, but the actual temperatures within the combustion chamber are much, much lower. And, once you’ve formed a protective cake on the bowl’s surface, assuming you’re not puffing like a locomotive, I’d expect the olive wood pipe to last a very long time. The one I have shows no signs of damage after several years of smoking. As for its smoking qualities, I found the olive wood to have a unique taste, especially in the early bowls, but after a dozen or so smokes, the difference isn’t dramatic, and can easily be masked by stronger tasting tobaccos. I see olive wood, like strawberry wood or bog oak, as just another option for pipe makers and smokers to explore.

That’s it for this month. Keep those cards and letters coming in, boys and girls. Now that Pipes Magazine has some swag available via the Cafe Press website, maybe a secret decoder ring is just around the corner.

-glp

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. See our interview with G. L. Pease here. |

Greg

Great article – very impressed by the extended experiment on cleaning. Must say I am not surprised the tobacco involved in Adam’s problem was straight virginia as I have found it gives a sour/stale taste to a pipe relatively quickly but mixtures do not. Even, surprisingly, one high in virginia and with cigar leaf (Key Largo) or one high in virginia with burley & possibly kentucky (Briar Fox). The solution is unlikely to be alcohol cleaning after every use as surely there is a risk that the stem will absorb alcohol and when heated during the next smoke it will evaporate into the smoke stream and colour, or as it is neutral spirit, de-colour the taste. One possible if rather extravagant answer is to follow your middle option cleaning thoroughly with pipe cleaners and occasional alcohol cleaning when necessary but use whisky, bourbon or cognac according to preference so that an extra taste is thrown in the mix rather than what may be a bit of a taste blanket.

So to the real question of the moment; when, oh when, is Sixpence due?

Regards & good luck with it,

Ed

“Nicotine stimulates the release of dopamine, a powerful neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, in the brain, and while the effect of this direct stimulation is fairly short lived……”

It’s also worth noting that research, documented in Dr. Fred Hanna’s book The Perfect Smoke, shows a long term beneficial effect of nicotine in preventing/slowing degenerative brain disease such as Dementia, Alzheimers and Parkinsons.

“These pipesters insist that cleaning a pipe too often and too thoroughly actually decreases the pleasure it delivers in the smoke. ..”

Again, from Fred, sometimes the bad taste in breaking in a pipe, arising from uncured saps etc., can actually lead to an eventual better smoking pipe as the become cured (as in maple syrup from sap).

I’ve always felt that you can clean a pipe too frequently. I think a balance has to be struck. For my tastes, after each bowl I wipe the chamber with a paper towel and run a dry cleaner thru the stem. With this method, I haven’t felt or tasted the need to do any “deep cleaning” with alcohol, brushes, etc. That is with a fairly large rotation as daily use adds to the equation and balance factors.

Ed, for me, there have always been tobaccos that are “pipe sensitive,” and those that are less finicky. For the most part, I’ve found mixtures to fall into the first group, and virginias, unless they are very full flavored, to land in the second. I’ve more often had a pipe that enjoyed a successful conversion from mixture to VA (I’m smoking one now, in fact) than the other way round. Never could quite figure that one out. And, it’s not so much a matter of taste, as a matter of teeth; a mixture in a pipe that doesn’t like them stings me like a mouth full of mad hornets. And, I certainly agree that dipping a cleaner or two into a preferred spirit can bring a nice nuance to the next smoke or two, especially if enjoying a wee dram at the same time.

.

Then again, I recall one of my early mentors telling me, when I was having problems with a particular pipe smoking well, to “smoke the hell out of it.” More than one way to skin a cat, I suppose.

.

Jim, Fred and I have discussed the second matter more than once. I think it was probably a more significant factor in the past, but with today’s briar treatment, with most mills exorcising the evil from their blocks through long boiling before sale, it seems to be less of an issue, especially with the hand-made pipes that Eric is talking about, which are made from carefully chosen briar, properly cured. Of course, briar remains a mysterious substance. I think this is due to it containing the as yet undiscovered 119th element, Briarium. (Of greater concern is some factories’ insistence on dunk-staining their finished pipes…)

.

And, as Mr. Jones says, balance. Isn’t that always the key?

I really enjoyed this installment and the ensuing discussion. I think a Brigham pipe, with its rock maple filter (shank/stem liner), would be a good platform for comparing the performance of squeaky clean vs. “seasoned” wood.