G. L. Pease

Amongst pipe tobacco aficionados, there seems to be no end to tightly held beliefs, some of which may have at one time had a basis in reality, some of which seem to be just frivolous flights of fancy. We are participants in a pastime rich with both history and romance, and the intersection of these presents an interesting playground for speculation and folly. Usually, it’s all in good fun. We love the colorful stories of briar and burl and leaf and smoke and the many characters that surround them, and some stretching of truths only seems to add to the mystery. With that in mind, let’s dive in to this month’s first question.

Amongst pipe tobacco aficionados, there seems to be no end to tightly held beliefs, some of which may have at one time had a basis in reality, some of which seem to be just frivolous flights of fancy. We are participants in a pastime rich with both history and romance, and the intersection of these presents an interesting playground for speculation and folly. Usually, it’s all in good fun. We love the colorful stories of briar and burl and leaf and smoke and the many characters that surround them, and some stretching of truths only seems to add to the mystery. With that in mind, let’s dive in to this month’s first question.

From Jan: My general question arose from a discussion with a fellow pipesmoker about basic tobacco manufacturing processes and who better suited to resolving this than a professional blender such as yourself? He stated that all tobacco is pressed during the first fermentation immediately after harvest and that as a consequence, all the tobacco we smoke has at one time or another seen the inside of a press at least once and most of it even twice (in what used to be called the cavendish process). I disagree and tried to make a guess as to what percentage of the total volume of pipe tobacco winds up in our bowls without ever being pressed: 30% would seem believable to me. Would you agree with my (not-so-dear-anymore) friend, or is my assumption reasonably correct?

A: A great question. I hope you don’t lose a friendship over this, but the answer is that you’re both a little right. How can that be? Once harvested, we know that the leaf must be cured, either by air, by heat (in the case of flue-curing) or by sunlight, which kills the leaf, dries it to the correct moisture content, and makes it ready for subsequent processing. Additional steps, such as the smoke fumigation of dark-fired and latakia types, may then be performed. Following this, the leaf must be fermented and aged to mellow it out. Usually, this whole process takes a minimum of 18 months, and can be as long as several years.

The fermentation that occurs during the initial aging is most commonly accomplished by stacking the cured leaf into pylons of 100 pounds or so, which are wrapped and tied in burlap, and allowed to sweat, the internal temperature and humidity closely monitored, for several weeks. As the internal heat rises, the stacks will be broken apart and re-stacked several times to prevent the leaf from decomposing. During this critical process, ammonia is released and sugars are converted, resulting in a more palatable product. After this, the stacks of tobacco are dried and further aged until they reach their optimum flavor and aroma, at which point they’ll be ready to blended and/or cut.

Your friend is partially right, in that nearly all tobacco at one time in its manufacture visits a press, though usually, only very briefly. During the cutting process, the bulk tobaccos are conditioned to the right moisture level for handling, then pressed into fairly loose blocks in order to be fed through the cutting machinery. Some machines in larger factories perform this pressing automatically as part of the production line, in other cases, it’s a separate step. Either way, this pressing step is purely mechanical, having nothing to do with altering the characteristics of the leaf. In other words, it’s not really pressing in the way that we normally think about it.

In some cases (such as in my Old London Series) the blends are assembled from whole leaf strips (leaf with the midrib removed), pressed into cakes, and allowed to age a bit before being cut. This is a method that was once common in some of the blending houses of the UK, but is rarely done today. Here, the pressing is more than just a way of holding the tobacco together for the cutter. It allows for a secondary fermentation to take place, while also increasing the integration of the various components of the blend into a more cohesive whole.

Pressing and cake-aging are most commonly seen in plugs and flakes, though, as you mention, there is also the so-called “cavendish” process, in which the leaf is sometimes sugared, and pressed in heated, usually steam jacketed presses before being aged and cut. This causes a significant darkening of the leaf, and the mellowing and deepening of the sweetness. But, if all tobacco were treated this way, it would present a pretty monotonous landscape. And, some tobaccos don’t respond well to this treatment. Orientals, for instance, lose much of the delicate perfume if hot-pressed.

Take your friend out for a beer and a great smoke, tell him you’re both right, and have a laugh over it.

Tony excitedly exclaims: Hot Damn! JackKnife RR got a review on PIPESMAGAZINE! 8oz. tins on the way? Yeah, I know it’s got to sell a bit first but I have hope. Putting a 8oz. tin of that wonderful herb up for a while excites the heck outta me. I can ‘see’ the tins in my mind’s eye. “@” Look real hard in the middle here…you’ll see them. I saw the 8oz plug at Smokingpipes.com. nice move. Can you get Pipesandcigars.com to handle it? I’d rather deal with them exclusively like I have been for the past year or so.

A: Starting with the last point first, though I make recommendations to retailers based on popularity of specific blends, I can’t really “get them” to stock things they don’t want to stock. Honestly, they’ll listen to their customers’ requests a lot more attentively than they’ll listen to my ultra-suave sales pitch. “Is this the pipe shop? Are you the manager? This here is the real G.L.Pease – you mighta hearda me. You might better get some of this JackKnife Plug in the big cans, or I’m gonna have to come on down there and whup your ass. My boy’s gonna come on down with me, and he’ll whup your ass, too, just for good measure. So, how many cans should I put you down for today?”

As to the JKRR in bigger tins, we’ll throw it at the wall at the next shareholders meeting, and see if it sticks. (Seriously, it might be just about time to do it. )

Kevin drops and rolls under the flames to pen: How could I get a pipe so hot as to burn the wood inside the bowl, but not experience any discomfort or foul taste while smoking? At least until I tasted the wood burning.

A: Pipes are mysterious objects. I’ve had pipes get so hot in my hand that I had to hold them by the shank, yet deliver a remarkably cool smoke with not even a hint of burnout, and pipes that felt cool to the touch, but emitted from their nozzle something like the exhaust gasses from a Saturn V rocket rather than cool, tasty tobacco smoke. In other words, I don’t have a freakin’ clue, but I have a suspicion that you’re just the sort of smoker waterglass bowl coatings were invented for. Did you see the memo about this? Yeah. I’ll go ahead and make sure you get another copy of that memo, okay?

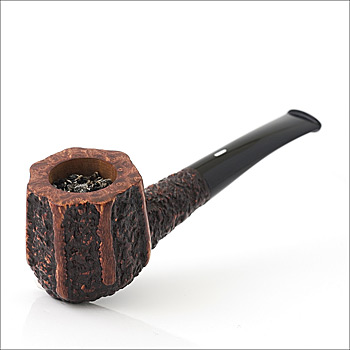

Tonyy writes: Gregg can you tell us something about what the Castello Sea Rock finish is and how it is made? I purchased a Castello estate for a song and just because of the price and the fact that I wanted a Castello someday I went for it. Smooth is obvious and Sandblast, a decent one usually shows the grain pattern. But Sea Rock? I don’t have a clue.

A: The Sea Rock is a type of rusticated finish that is done by hand using a tool that chips out pieces of the briar. Rather than exhibiting the grain in relief the way a sandblast would, rustication of this form gives the pipe maker more leeway in determining the pattern of the pipe’s surface. The Sea Rock finish has taken different forms over the years, starting out with a very interesting, craggy form similar to rough corals smoothed through years of tumbling in the ocean (hence the name), and more recently, a tighter, more even style. An interesting variation of the Sea Rock finish is the “∏” (pi) variant, which incorporates smooth areas. (On older examples, this variant is indicated by the digit 3 proceeding the regular shape number.)

PipeGazette did a wonderful video interview with Castello’s Franco Coppo in which part of the process can be seen (2:25).

That’s it for this month. As always, keep those cards and letters coming. What are those burning questions (groan) you’ve always wondered about? Send them in! I love a full mailbag.

-glp

Photo Credits:

Castello Pipes and opening photo of pipe shadow on book by G. L. Pease

Pressed tobacco taken at Cornel & Diehl Factory by Kevin Godbee

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. See our interview with G. L. Pease here. |

Great information as always. Thanks!

I particularly enjoyed you’re mention of “killing the leaf.” I enjoy your articles. Thanks Greg!

Thanks for another informative and nicely illustrated article. They’re always a great read too!

Tony, I’ve passed your request on to our buyer so he can include the 8 oz. JackKnife Plug in our next order.

Russ

Looking forward to seeing Greg & Russ at the KC Pipe Show.

I think the elephant in the room with the first question is the introduction of the Cavendish process into the discussion; the answer implies (expresses?) the fact the Cavendish tobacco requires the addition of a sweetening agent and is not just about stoving – an important distinction?

On a later point, Fred Hanna has covered this in a way that, for me, could not be better expressed; basically, the main concern for the smoker is the temperature of the smoke (and this can never be below ambient unless your pipe has a cooling unit) – the felt temperature of the pipe is irrelevant to the smoking and is entirely dependent on the insulative/conductivity properties of the briar.

Thank you for your very clear and extensive response. With this in hand we might even get to sharing that beer, some day :).

Jan

Firing a bowl while reading your articles always makes for a sweet afternoon. Thanks Mr. Pease.

D

Consistently charming, informative, and fun articles. Q: When are you planning to come out with the hard-bound collection? Paperback?

Very good information as always!

Thanks!