Alan Schwartz

What do you have when you take the best piece of briar you can find, cut it and shape it by hand, buff it to ultimate smoothness, fit a hand-cut mouthpiece individually crafted to complement the bowl, and polish it with pure carnuba wax to enhance and protect the wood grain with a brilliant luster? Most likely a fine quality handmade briar pipe that will please any smoker. But will it satisfy the demanding standards of Richard Dunhill, who alone decides which of the top-quality pipes his company produces deserve the highest accolades? That is another story, as Dunhill’s rigorous grading process determines the following designations for the famed line of Dunhill pipes:

What do you have when you take the best piece of briar you can find, cut it and shape it by hand, buff it to ultimate smoothness, fit a hand-cut mouthpiece individually crafted to complement the bowl, and polish it with pure carnuba wax to enhance and protect the wood grain with a brilliant luster? Most likely a fine quality handmade briar pipe that will please any smoker. But will it satisfy the demanding standards of Richard Dunhill, who alone decides which of the top-quality pipes his company produces deserve the highest accolades? That is another story, as Dunhill’s rigorous grading process determines the following designations for the famed line of Dunhill pipes:

- Which pipes shall bear the coveted Dunhill designations that say, these are the best of the best, from the best?

- Which pipes shall be ranked not only the highest of the high, but the lowest of the high?

- Which pipes shall sell in the Dunhill shops and through the principal pipe dealers of the world for prices that are about ten times what the best pipes from other makers can command (and be sold-out often before they are ever displayed)?

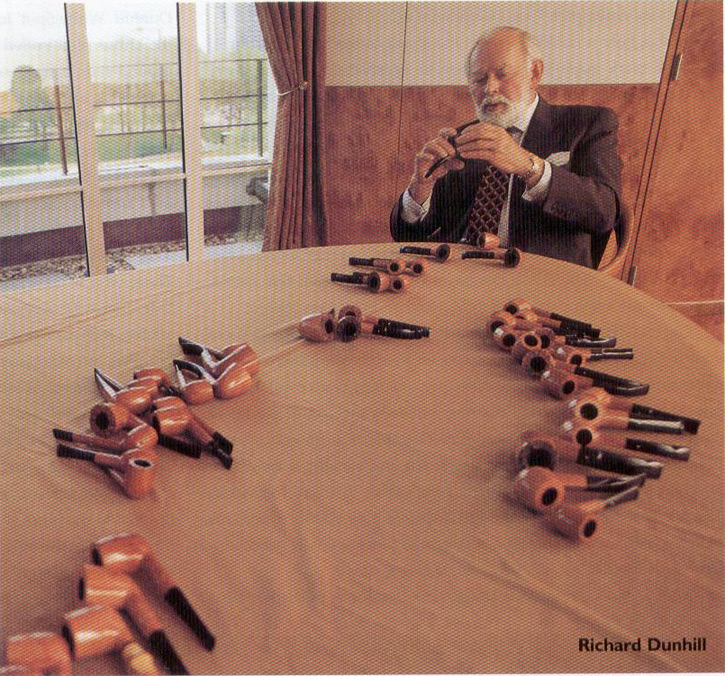

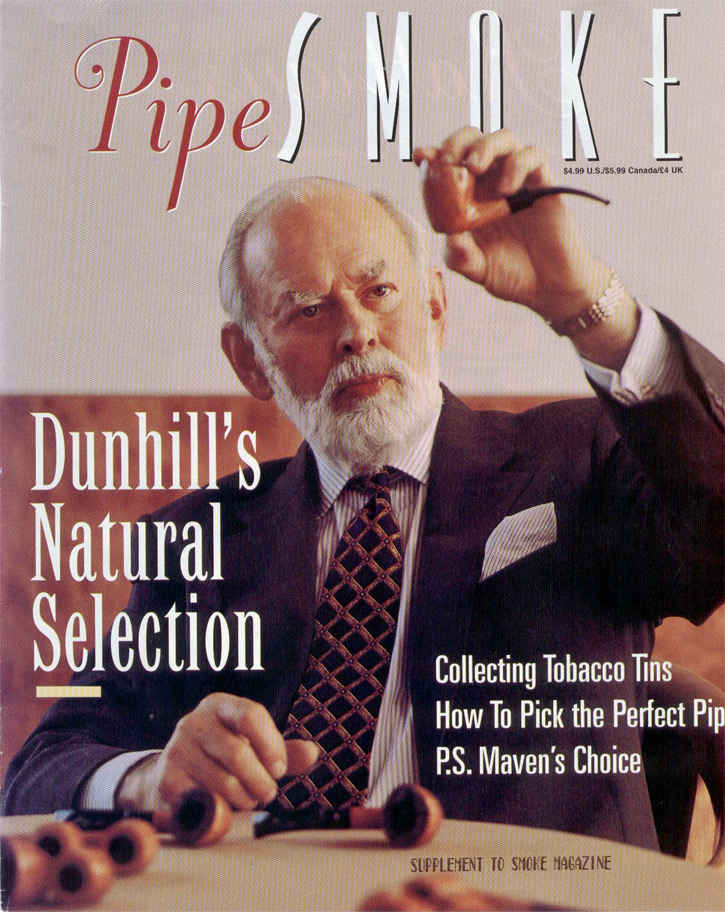

In his office and corporate boardroom high above London’s Knightsbridge Road, overlooking Hyde Park and Marble Arch, Richard Dunhill sits and passes judgment. Bearded and affable and ever the English gentleman, the man who bears the proud name of the best known pipes on the planet is the lord of his domain, deciding on the rank and status of the hand-crafted work his artisans have produced. The judgment day occurs twice a year, when a small, pre-selected group of pipes are brought from the Walthamstow factory to London to have their fates determined by the pipe king. Benign though judgmental, Richard Dunhill gives all pipes his preference as he determines the “survival of the fittest.” PipeSMOKE was lucky enough to recently witness this process firsthand, from the making of a Dunhill through the final judging, so we could share it with our readers.

A DUNHILL IS BORN

We start in the Walthamstow factory in east London with Simon Glendenning, a thirty-something marketing specialist whose early experience was in the wine business, before he came to Alfred Dunhill Pipes Limited as general manager. Glendenning, along with David Webb, the operations manager, escorts us as we walk through the factory to watch some top-of-the-line pipes being cut by hand. Production supervisor Steve Wilson, a master pipemaker who has been with Dunhill for 27 years, locks an ehauchon (precut block of briar) into the chocks of his lathe, starts the machine and begins the "fraizing" (rough cut). Using only hand tools that he’s made himself from basic chisel blades mounted into wooden handles — "Nobody makes these commercially, so every pipemaker has to grind his own," he says — he shapes the outside of the bowl first, letting the grain of the wood determine the form.

A preliminary examination of the wetted block shows the pipemaker whether the outer grain is straight or splays out ward. If it’s straight, he’ll try for a "billiard" shape with parallel sides. Should the grain splay outward evenly, he may attempt a "Dublin" shape, a cone that narrows downward from the top. Variations abound. Some blocks are tossed aside before the first cut: a first step in Dunhill’s "natural selection."

"For these handmades, we use only plateau briar, the outer cut of the runt with the rough, gnarled surface," Steve explains, "because there’s a greater chance for perfect grain than with an inner cut of wood. That gnarled surface is always at the top of the block if you are cutting for straight grain. If placed sideways, the result will be a cross grained bowl with the tight little swirls known as birdseye."

With only a sharp chisel supported on a low T-bar (the "horn") mounted to the bench, Steve cuts the outer bowl to the size he wants, determined by a circle he has scribed on the surface with a sharp point. When the outer surface is completed, Steve uses a triangular blade to cut the tobacco chamber, applying continuous pressure into the top of the bowl, guided only by his hands. The blade is supported by the "horn" with no drill, no proscriber, nothing to measure the exact center but his practiced eye.

When the bowl is done, the block is shifted on the lathe and a similar process of turning and cutting the shank is completed. The only difference is that the shank will be drilled later to make the airhole fit the mouthpiece. Steve drills a small guide mark in the center of the shank for the mouthpiece maker.

After a rough sandpapering, the bowl is inspected and joins a pile of others already sorted into those that made the cut and those who didn’t. "This is the pipemaker’s heartbreaker," Steve explains, gesturing towards the pile. At the last moment a flaw in the wood appears: a fissure, a sand spot, an ungrained, bald spot. These pipes, of the same quality briar as the unblemished ones, will smoke just as well and yield as much pleasure as the perfect specimens, hut won’t become Dunhills, because Dunhill will not use putty fillers to conceal flaws. Only those bowls with the greatest chance of bearing the brand name get the attention needed to survive. A small selection of the wounded will be treated by sandblast, and if the blasting removes the offending blemish they will then become "Shell Briar," the company’s trade name for its rough-textured finish.

Because Steve has been cutting plateau briar for straight-grained specimens, the ones that are sandblasted will show the grain and become the coveted "shilling grain," which invariably appears as a pattern of rough ridges ringing the outside, adding a horizontal topography to the vertical straight relief grain.

The next step is fashioning a mouthpiece and fitting it to the bowl. Individually made from solid rods of hard rubber that are separately drilled, shaped, and formed for each pipe, the mouthpieces emerge after an extremely labor intensive process that adds tremendously to manufacturing costs. However, Dunhill won’t do it any other way. "There’s more work in one of our mouthpieces than in some of our competitors’ entire pipe," says Clendenning.

First, a hole is drilled through the shank to the bowl, starting at the guide mark made by Steve when he finished turning the bowl. This tunnel must emerge in the bowl so that the bottom of the tobacco chamber and the bottom of the airhole are at exactly the same level. Too high and the bowl base will accumulate excessive moisture, will gurgle and smell foul. Too low, and it will not draw properly.

First, a hole is drilled through the shank to the bowl, starting at the guide mark made by Steve when he finished turning the bowl. This tunnel must emerge in the bowl so that the bottom of the tobacco chamber and the bottom of the airhole are at exactly the same level. Too high and the bowl base will accumulate excessive moisture, will gurgle and smell foul. Too low, and it will not draw properly.

Many brands, including those that Dunhill manufactures under trade names, are fitted with preformed, molded, and mass-produced mouthpieces. There is nothing wrong with that but the Dunhill practice is different. "The consumer pays the price indeed, but it’s for more than just a name on indifferent merchandise," says Webb.

The end of the shank is then mortised to a width of usually six to eight millimeters and a depth of sixteen to eighteen millimeters, to accommodate the mouthpiece tenon (peg), usually twelve millimeters long, leaving a small smoke chamber between the end of the tenon and the beginning of the airhole. This chamber is supposed to slow down and cool the smoke stream. While the functionality of the chamber is hotly debated among pipemakers, suffice it to say the smoke chamber is characteristic of the English-style pipe. Dunhill, perhaps the most traditional pipemaker in England, "does it this way because they’ve always done it this way," according to Steve.

After a tenon is fashioned, the mouthpiece rod is pushed into the shank mortise, but not all the way, so that the airhole can he drilled, the rod sanded down to proper size, the lip cut and shaped by file, the Dunhill ‘White Spot’ logo drilled into the top of the mouthpiece, and the entire pipe buffed and polished. If stain is called for, the background stain is hand-rubbed and then burned off and sanded so that it remains only in the softer wood between the harder grain lines.

Later, the pipe is re-stained in a complementary color, for grain contrast, before the final waxing and huffing. At this point, the pipe is a regulation Dunhill, and the crétne de la créme is now set aside for the final approbation of the reigning monarch, Richard Dunhill.

THE SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST

Those who work with the chairman of Alfred Dunhill, Ltd., call him "Mr. Richard," reflecting the deference he commands. Courtly and affable, Richard Dunhill puts his visitors at ease by offering not merely coffee, but espresso from the special machine he’s installed, serving the brew himself in white china cups. He tells us about the paintings on his office wall and talks of a recent discovery of his, a Dunhill car. He didn’t know they existed when he discovered that 120 were made in France in 1912 — and he’d like to buy one from a collector. With the comfortable rapport of our host/guest relationship established, we proceed to the pipes.

Dunhill, who still blends his own tobacco, leads us to the board room, where a large bolt of Alpaca fabric has been unrolled on the boat-sized table, to prevent scratching of the pipes. "I bought this fabric for something or other years ago," Mr. Richard says, "but I can’t remember what for. So now it .. serves a nobler purpose." He then proceeds to lay out the pipes with the help of Simon Clendenning, to correspond with the basic shuffle the factory inspectors have already prepared.

"You know this is the prerogative of the chairman," he says, "and I wouldn’t miss it for the world." His company, now part of the Vendome Group Portfolio, which includes Cartier, Montblanc, Piaget, Baume & Mercier, Karl Lagerfeld, Sulka, Hackett, Chloe, Seeger, and James Purdy & Sons, has become one of the world’s foremost purveyors of luxury goods, and pipes make up a very small part of its annual turnover. But briarwood is in Mr. Richard’s soul: "Pipes are our heritage. If we hadn’t had that pipe, we wouldn’t be here. Pipes were our number-one product for years, then lighters outstripped pipes, now it’s fashion and leather goods, but this is where it started."

There’s something reverential in the way he proceeds in this task, performed once every six months, this time to grade 64 pipes, which are the top selections from the entire production run from the past half year. His method is simple, but based on a lifetime of experience. The pipes have been presorted into eight grades, from one star to six stars, and then "G" and "H," with the last being the highest. Thus, a one-star pipe will retail for around $785 to $850 (U.S.), while a six-star pipe will cost from $3,100 — $3,500. "G’s" are in the $5,000 range, and "H’s" flank both sides of $8,000, depending on the size.

But Mr. Richard is not grading for size; only quality. "What I’m looking for is consistency," he says, showing us three Canadian pipes (billiard-style bowls with extra-long oval shanks and short mouthpieces) that he’s pulled out of their pre-assigned lot. "The grain here falls away slightly off the vertical," he says, pointing to the bowl, and the grain along the sides of the shank runs off at a 45-degree angle. It’s a one star. Beautiful indeed, but not perfect." Another has straight grain all around, but on one side of the bowl the striation is sketchier than on the other side. "That’s a three-star." The third Canadian is perfectly even on both bowl and sides, but "the grain is less dense, slightly more open than I’d call a six. It’s a four, maybe a five, we’ll see later," he says, setting that pipe aside.

During the entire process, Mr. Richard sets aside only one "H," a medium-sized classic billiard in the style that is almost synonymous with the traditional Dunhill pipe. The visual relationship of bowl, shank and mouthpiece is perfectly proportioned, and the grain is close, dense and invariably vertical from top to bottom, and of even density all around the bowl and on the shank. The bottom of the bowl and top of the rim, as well as the bottom and top of the shank, show an even display of tightly knit birdseye, so evenly distributed that it looks as though it has been drawn in place. "Now, that’s perfect, in every way," he says with the pride of a parent whose offspring has walked away with the highest honors. "Perfect!"

This pipe will go to the flagship Dunhill shop on the comer of Duke and Jermyn streets in the heart of I.ondon’s most fashionable St. James’s district. Who will buy it? "A collector who will treasure it as I do," Mr. Richard answers, "maybe someone like the Sultan of Brunei, but probably an American. They really appreciate our work in your country." Will the buyer smoke it? "Oh, perhaps occasionally," Mr. Richard says, "in good company where it will be appreciated." And then adds with a twinkle in his eye, "But it would be a pity, wouldn’t it?"

PipeSMOKE Fall 1997

Thanks Kevin for republishing these older articles. They are always entertaining and interesting. I enjoyed this one since I have steadily become a fan of the iconic brand. I’m still considering exactly what Mr. Richard meant by that last line. I hope to think he meant a pity that it only would be smoked occasionally.

Really nice article. It harks to the old days when company honchos stayed in touch with their product.

Thanks to Alan Schwartz and Kevin Godbee for making this article available once again.

What a fine article! Thank you for publishing it. First I thought Dunhills were not a good value for the price, then that although they are a good value, they were still too expensive; but after reading this I’m thinking they’re good for both.

And I want one!

A fascinating article. I find it very reassuring that Dunhill as a company still takes it’s pipes seriously, although it’s a great shame that when you walk into any Dunhill shop all over the world, there are no pipes whatsoever to be seen amongst the Cologne, Polo Shirts, ties, etc.

I miss the day when you could walk into Dunhill in Jermyn Street and sample the various hand blends, and ogle the pipe display.

I was recently at the Dunhill shop in Duke street and even there, there was no sign of Dunhill’s pipes– just some cheaper Comoy’s.

If pipe smoking world-wide is indeed having a “renaissance”, then maybe it’s about time to ignore the anti-smoking lobbyists and start displaying and selling these briar works of art in the Dunhill shops in major cities and even in the major airports again.

I remember buying an ODA 835 in Sydney’s Dunhill shop back in the late ’70’s, but now that’s just a fond memory.

Great piece. In a single article you wiped away all the dismissive blogging about Dunhill.

Do they smoke an better than a Castello or Moretti? The price they command is only by way of someone buying them.

I know Mr. Dunhill is committed to his iconic brand, but this is almost downright British snobbery. Good show ole boy indeed.