G. L. Pease

Some really interesting questions fell out of the mailbag this month, with topics ranging from humidification, to tobacco colors, to blending, to toxicity. For a change, though, it’s not the toxicity of tobacco that’s in question, but rather that of flavoring agents, and of different woods when used in pipe making. Some fascinating and challenging stuff. So, without further ado, grab a pipe, find a comfy spot, and let’s dive in.

Some really interesting questions fell out of the mailbag this month, with topics ranging from humidification, to tobacco colors, to blending, to toxicity. For a change, though, it’s not the toxicity of tobacco that’s in question, but rather that of flavoring agents, and of different woods when used in pipe making. Some fascinating and challenging stuff. So, without further ado, grab a pipe, find a comfy spot, and let’s dive in.

Eric writes: I use the small "Immerse Humidifier" in my tobacco pouch to keep the tobacco from drying up too much. It says to immerse in cold water; however, I have some Propylene Glycol solution I use for for cigar boxes and have used that to moisten the humidifier. It seems to work fine. But I have noticed you speak of PG as a agent for sweetening tobacco. Am I inadvertently sweetening my British blends? Should I just use water?

A: Using PG in humidifying devices is not the same as applying the stuff directly to the tobacco itself. The vapor pressure of PG is much lower than that of H2O (about 0.1 mm Hg vs. 17.5 mm Hg at 20˚C), so any moisture added to the tobacco by the device will be predominated by plain water, so, the PG isn’t likely to cause any noticeable change to the flavor of your tobacco. But there’s no real advantage to using the stuff, so why not just use water, or for that matter, nothing at all? A well-made pouch should maintain your tobacco in fine smoking condition for at least a couple of days unless you are in a very dry environment. And, remember that if you’re losing moisture, you’re also losing aroma and flavor. If your pouch isn’t sealing well, it might be time to replace it.

It’s also important to remember that tobacco must not be allowed to get too damp; mold is a much bigger problem than dryness. When the moisture content rises above a certain level, usually too damp, really, for good smoking, any spores that are present may germinate, and in a matter of days, depending on conditions, you might find yourself with a moldy mess, necessitating discarding the tobacco, and cleaning the pouch thoroughly. It’s probably best just to keep your pouch filled with a day’s ration, and keep the rest in a well sealed jar.

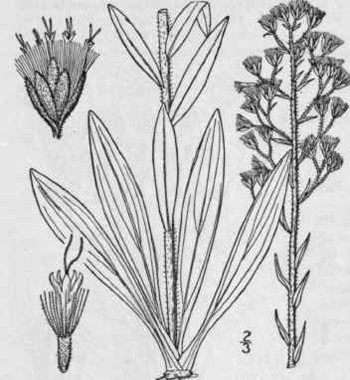

Kaos, and a few others wonder about red virginia: I’m a young Italian pipe smoker and I’ve enjoyed so much many of your wonderful blends I had the luck to purchase during my travels. I still have many at home preserving them carefully. I’m fond of every sort of virginia and I’m now just curious to know: Are red virginias from specific seeds, or are they a specific kind of cure of virginia leaves? Thank you so much for your reply and for your great tobaccos!

A: It would sure make everyone’s life easier if the growers could just plant a seed that guaranteed a specific end result, but unfortunately, it’s not so simple. What follows is a very brief look at some of the factors involved. A more complete discussion would require at least a full column, and if there’s sufficient interest, I may do something more in-depth in the future. (And how will I know there’s interest, you may ask? Use the comment section down there at the bottom…)

A: It would sure make everyone’s life easier if the growers could just plant a seed that guaranteed a specific end result, but unfortunately, it’s not so simple. What follows is a very brief look at some of the factors involved. A more complete discussion would require at least a full column, and if there’s sufficient interest, I may do something more in-depth in the future. (And how will I know there’s interest, you may ask? Use the comment section down there at the bottom…)

Seed stock, soil type and fertilization methods, climate and environmental factors, stalk position, agricultural management practices, harvesting method, such as priming (picking individual leaves) or stalk cutting, curing and post-processing all have influences on the final color, sugar level, nicotine content and smoking characteristics of the finished product. In other words, there’s not one factor that determines color; every step from seed selection to finished mixture plays a part.

Some seeds, of course, are better suited for producing bright yellow through orange tobaccos, while others are chosen for their darker finished shades. Additionally, stalk position plays a part, with darker leaves growing towards the top where sun exposure is greatest, but, a plant selected for bright leaf won’t generally produce dark reds or brown grades, and vice versa.

Climate is a significant factor, as well. Wetter years will produce tobaccos with higher sugar and lower nicotine, while drier years will result in opposite qualities. The higher the sugar content, generally, the more likely the leaf is going to color-cure to a brighter shade, but there are also some very sweet reds grown.

Longer cures tend to produce darker shades, at the expense of sugar levels. (One aspect of curing that is particularly difficult with brighter, sweeter brights is that the leaf must be "killed" quickly enough to maintain its high sugar levels and set the color, but not so quickly as to prevent complete yellowing. Brights that are cured too quickly may remain green, and even if they survive the following aging process without rotting, won’t be suitable for smoking.)

Of course, there’s some confusion on the consumer side about how "red virginia" is defined. At the point where the tobaccos are aged and ready for purchase, they’ll have shades ranging from bright yellow through orange to deep red or brown, but once blended, pressed, cake-aged, steamed, toasted or otherwise processed, they will often darken significantly; what began its journey as a yellow or orange grade might end up masquerading as a red. Confusing, innit?

From a blender’s perspective, it’s the taste that matters more than the actual color of the leaf. Brights can be characterized as being sweet, slightly sharp, with additional citrusy, sometimes grassy or hay-like characteristics, while reds tend to present a deeper, more complex sweetness with a sometimes noticeable earthiness and more plummy or berry-like fruitiness. Of course, further fermentation and aging will result in changes to the finished blend, as well, with more fruity and wine-like characteristics becoming increasingly dominant, and often cocoa, coffee and spice flavors finding their way to the party. The point is, what’s red in the tin might not have been red in the shed.

Jim is a woodworker who wants to know about other woods for pipes: I recently purchased a Plateau Briar pipe kit and had a great deal of fun creating, what is fast becoming, my favorite pipe. Being a retired scroll saw artist, I have many beautiful exotic hardwoods in my shop. So naturally I have thought of creating some home made pipes, but one thing bothers me. Many of the hardwoods I have caution the woodworker to wear a mask when cutting & sanding these woods due to harmful byproducts contained in them. While I realize the precautions apply to working the wood & breathing in the dust, I wondered if these woods, Bocote, Cocobolo, Zebrawood, etc. might be harmful when used for a pipe. Could you give me any information on this?

Jim is a woodworker who wants to know about other woods for pipes: I recently purchased a Plateau Briar pipe kit and had a great deal of fun creating, what is fast becoming, my favorite pipe. Being a retired scroll saw artist, I have many beautiful exotic hardwoods in my shop. So naturally I have thought of creating some home made pipes, but one thing bothers me. Many of the hardwoods I have caution the woodworker to wear a mask when cutting & sanding these woods due to harmful byproducts contained in them. While I realize the precautions apply to working the wood & breathing in the dust, I wondered if these woods, Bocote, Cocobolo, Zebrawood, etc. might be harmful when used for a pipe. Could you give me any information on this?

A: This is a tough one. As you note, many exotic and common hardwoods have some level of toxicity when handled and worked, either as a result of exposure to their sawdust, or to handling the saps and resins in the wood itself. Though there’s quite a bit of information available regarding relative toxicities, this information applies primarily to working with these woods or in some cases to eating/drinking from utensils or vessels made from them, not to smoking pipes made from them. These toxins can cause symptoms ranging from mild itching/irritation to rather more dramatic reactions. The list of woods with known toxicity is surprisingly long, and few lists are extensive. One excellent resource can be found in the Health and Safety Executive report, Toxic Woods.

"It is an ascertained fact that travellers’ vessels, made in Gaul of this wood (Yew), for the purpose of holding wine, have caused the death of those who used them."

-Pliny the Elder, "Naturalis Historia" circa 77 CE

Finding reliable information on the potentially harmful effects of these woods if used in pipe making is more difficult. Those listed as "direct toxins," such as mangrove, yew and others, can be hazardous or even fatal under some circumstances, and they should obviously be avoided. Woods listed as irritants can result in itching, dermatitis or respiratory discomfort from exposure, while those listed as sensitizers are like allergens; there may or may not be an immediate reaction, but over time, symptoms may develop, often becoming worse with increased exposure.

Fruit woods, like apple, cherry, olive and pear are probably the safest of the non-traditional woods, but they tend to burn fairly easily, often chip or crack, and probably aren’t ideal for pipes with long life expectancies. But, even briar, the king of pipe woods can be an irritant or sensitizer to some individuals, and some pipe makers have developed a reaction to its dust over the years. As a material for smoking pipes, though, it seems relatively harmless.

If you’re going to use exotic woods for pipe making, do thorough research, and proceed with caution. Looking up what the potential toxins are in a particular wood, and researching those would be a good start. Safe is better than sorry. And, of course, good dust collection and protective clothing and eyewear is always recommended, especially important if you’re predisposed to sensitivity.

From Arno: Recently a friend of mine opened up a 6-year old tin of Samuel Gawith’s Navy Flake. The flakes were speckled with white spots. First we thought, yummie, sugar crystals! But we really could not see any flickering of light from the crystals when we held the flakes in the sunlight.. So how do we know the difference between sugar crystals and mould?

A: First, it’s not clear those shiny jewels sometimes found on tobaccos are "sugar crystals," though they’re often referred to as such. Several times when I’ve discovered these glistening indicators of potential yumminess, I’ve done some rudimentary playing with them, though no full-scale analysis, and found them not sweet, not very soluble, and not very likely to be sugar. More likely, they are organic acids that have precipitated as a result of pH or other changes in the leaf’s chemistry as it ages. Nevertheless, the presence of these crystals usually indicates something good has happened to the tobacco that hosts them, and we’re generally rightfully excited to see them.

Mold, on the other hand, is rather different. How can you tell if it’s there? Your nose will offer the first clue. Moldy tobacco stinks in a way that is difficult to describe, but once you’ve smelled it, you’ll never forget it, and, most people wouldn’t even be tempted to smoke the stuff. Imagine the aroma of mildew combined with the ammoniac scent of soft, ripe cheeses well past their prime. If it was mold, I’m pretty sure you’d know it by nose alone.

From Russell in NYC: Hi Greg! My question is about how to add flavor to tobacco I’ve purchased from various vendors. I’m interested in buying some basic unflavored leaf, and then adding some aromatic oils (food grade!) to make my own flavored blends. For example, I bought some bergamot oil and added about a teaspoon to a 50gm tin of tobacco, then let it sit for a week to allow the oil to soak into the tobacco. The result had a great aroma and a very nice flavor when smoked, especially with a cup of Earl Grey tea. I wonder if this sort of experimentation is safe, and also if there are aromatic oils that are better for this type of home-made blending. I’d love to try this with almond oil, and maybe even spearmint or other flavors. I don’t like very sweet blends like cherry, or candy-flavored tobacco, but there are many oils that might make a nice custom blend. Any suggestions?

From Russell in NYC: Hi Greg! My question is about how to add flavor to tobacco I’ve purchased from various vendors. I’m interested in buying some basic unflavored leaf, and then adding some aromatic oils (food grade!) to make my own flavored blends. For example, I bought some bergamot oil and added about a teaspoon to a 50gm tin of tobacco, then let it sit for a week to allow the oil to soak into the tobacco. The result had a great aroma and a very nice flavor when smoked, especially with a cup of Earl Grey tea. I wonder if this sort of experimentation is safe, and also if there are aromatic oils that are better for this type of home-made blending. I’d love to try this with almond oil, and maybe even spearmint or other flavors. I don’t like very sweet blends like cherry, or candy-flavored tobacco, but there are many oils that might make a nice custom blend. Any suggestions?

A: Suggestions? Sure. First, be careful. Some essential oils can be toxic when ingested, and it’s pretty easy to find out about toxicity by doing your due diligence, looking up their MSDS, researching as much as you can before playing with them. For instance, almond oil (not extract) may contain cyanide (prussic acid), and is potentially lethal if ingested. These oils will volatilize in the smoke stream and precipitate in the mouth or the lungs. Anyone who has ever been near the smoke of a poison oak fire will know far too well how sinister oily smoke can be.

Almond essence, on the other hand, has had the cyanide removed through an alkali wash, but this has largely been replaced with synthetic flavoring. Even food grade flavorings are not necessarily safe when used "off label."

Of course, in most cases, the dose makes the poison. Wintergreen oil (methyl salicylate), for instance, can be used in minute quantities (up to 0.04%) as a flavoring agent, but in larger doses can be quite dangerous. Generally, food grade flavorings are used in such small amounts in tobacco blending that it’s unlikely that we need to worry much about them. A teaspoon (5ml) of bergamot essential oil, though, is quite a heavy application. I once, as an experiment, jarred up about 50g of virginia ribbon with a single Earl Grey teabag for a few weeks, and the presence of bergamot was quite pronounced in the tobacco’s aroma and flavor. Those volatile aromatics are pretty intense. (Keep in mind that essential oils are added by drops to alcohol to create things like after-shave lotions and Eu du Colognes. It doesn’t take much!)

Food-safe additives are less concentrated than essential oils, but caution should still be the watchword. On the rare occasions when I use these in blends, the quantities are measured in tenths or even hundredths of a percent by weight. For example, I might add 2% of a sauce to a blend, only a small fraction of that sauce being a natural flavor extract. Then again, I’m usually after subtle effects, not a full scale aromatic assault. Candy-shop blends use much more in comparison.

Thanks to the anti-tobacco zealots, there’s been full-disclosure by the big tobacco companies regarding additives, so it’s not hard to find on-line references on the myriad enhancers used in the tobacco industry, and often the maximum quantities regarded as safe are given. Again, do your research and proceed advisedly.

Arno asks: At home I like to blend my own mixtures. An ingredient that I often use is deertongue. Especially in English/Balkan blends it really shines. Most people who smoke my mixtures agree that deertongue adds a special element to a blend that they really like. Some kind of old-fashioned element. So why are there almost no mixtures with deertongue on the market and why did you never create one? I know in Europe (where I live) that it is a forbidden ingredient (you may eat it but not smoke it…) but in the States it is legal as far as I know.

A: The main problem with deertongue is finding a good, clean source of the stuff that isn’t hugely expensive. On a home-blending scale, it’s not such an issue, but on a commercial level, things get wonky. It’s much more expensive than tobacco, and by the time it’s cleaned, stripped, cut and made ready to blend, the cost increases significantly. To compound things, sources are not as reliable as we’d like them to be; if the hobby-blender can’t get an ingredient for a while, it’s inconvenient, but he can go on to other things. If a manufacturer can’t get it, on the other hand, it can reflect a significant hit to business.

A: The main problem with deertongue is finding a good, clean source of the stuff that isn’t hugely expensive. On a home-blending scale, it’s not such an issue, but on a commercial level, things get wonky. It’s much more expensive than tobacco, and by the time it’s cleaned, stripped, cut and made ready to blend, the cost increases significantly. To compound things, sources are not as reliable as we’d like them to be; if the hobby-blender can’t get an ingredient for a while, it’s inconvenient, but he can go on to other things. If a manufacturer can’t get it, on the other hand, it can reflect a significant hit to business.

The primary useful component in deertongue is coumarin, a flavoring agent with a somewhat notorious reputation. Some manufacturers who once used the herb replaced it with coumarin outright, then later faced problems when, in several countries, the use of coumarin as a tobacco additive (in the US, this was limited to cigarette tobacco) was banned. (If you want to read more deeply into this, or are just looking for a good sleep aid, click over to A Comparison of US and Norwegian Regulation of Coumarin in Tobacco Products.) So, though it’s still a useful ingredient for hobby blending, its commercial viability remains questionable.

Stephen wants to try blending, too, and looks for advice: I’ve returned to pipes which I haven’t tried since college in the early 80’s. Growing up I watched my father buy all sorts of razors notably looking for the elusive ‘perfect shave’. I feel the same with pipe tobacco. I’ve spent hours and hours reading at tobacco reviews, including your articles in Pipedia.com, and I want to try my hand at blending some pipe tobaccos, no doubt in the family tradition, only this time for the ‘perfect smoke’. I purchased various pure tobaccos, virginia, perique, latakia, burley, oriental, etc., bought clay pipes on ebay to use for tasting, etc. I would appreciate any suggestions from you regarding methodology and your suggestions on your blends so I can enjoy the pipes, rather than cigarettes in the meantime.

A: This is actually a popular question. Unfortunately, there is no methodology apart from hard work and careful note-taking. Blending tobacco is like cooking. You have to know your ingredients, and get to know how they interact with one another. It takes time to cultivate familiarity. Anyone can learn to cook, following recipes, maybe adjusting them a little to suit their tastes, but fewer have the discipline or the desire to become chefs. Tobacco blending is no different. Though the palette of flavors is more limited, there are time-consuming practices such as steaming, panning, toasting, pressing to learn about, plus the effect that time will have on the finished product. Something you may like when freshly blended might taste like lawn clippings a week later. (I’m not kidding. It’s actually remarkable how much change some mixtures undergo even within the first few hours of being brought together.)

With tobacco blending, there are no shortcuts, no culinary schools, no shelves of cookbooks or well tested formulae to follow. If you enjoy this sort of journey, which I suspect you will, you’ll probably find some pleasure in it whether or not you end up with your "perfect smoke." If you find that you do not, you may be better off buying something close to what you’re chasing from someone who has already done the hard work, adapting it to your tastes using what you’ve learnt from your experiments. Did I mention taking copious notes? Good luck, and enjoy the ride!

That’s it for this month’s edition. Hope you enjoyed it, and as always, keep those cards and letters coming. (And please, take a moment to comment below. It’s always great to hear from my readers.)

-glp

Since 1999, Gregory L. Pease has been the principal alchemist behind the blends of G.L. Pease Artisanal Tobaccos. He’s been a passionate pipeman since his university days, having cut his pipe teeth at the now extinct Drucquer & Sons Tobacconist in Berkeley, California. Greg is also author of The Briar & Leaf Chronicles, a photographer, recovering computer scientist, sometimes chef, and creator of The Epicure’s Asylum. See our interview with G. L. Pease here. |

Thank You again, for a very informative article.

Terrific as always Mr. Pease. It made my day reading this while puffing at some Haddo’s.

Thanks!

This is the most interesting “Ask G.L. Pease” in a long time. Additionally, G.L. Pease himself, is the real Most Interesting Man in the World, and Dos Equis modelled their advertising spokesman after him.

Any chance of you getting some Haddo’s over to Gauntley’s.

It is killing me that I cannot try your best reviewed blend!

A great read. Enjoyed it Thanks!

Thanks for the time and effort you put into these articles. They are a joy to read.

Greg, I would love a comprehensive full length article on the planting, cultivating, processing and curing of the various tobaccos. Very interesting topic you touched on– thanks!

Thnx for the read and for answering a couple of my questions! 🙂 Too bad it looks like there is no blend coming from your hand containing deertongue..

Another great article with lots of good information, thanks Greg!

Great article Greg. Any thought to putting your years of combined wisdom into book form, perhaps calling it “A Blender’s Tale”. I’m sure there’d be a market for it. Also, such a book would be a great milestone in the history of pipe tobacco and could go some way to educating the non-smoking public as to the intricacies of the Art. Like the art of fine wines and the upsurge in microbreweries, tobacco blending may catch the interest of the discriminating public, and, who knows, may even draw new members into the fold.

A Blender’s Tale? One of Chaucer’s lost works. I’ll have to brush up on my Middle English, as it’s pretty rusty these days.

Thanks, as always, for the words of support and encouragement, guys. It means a lot! And, spread the word! Tell a friend! The more readers, the merrier! (If my readership gets large enough, that book idea might not be a bad one…)

I’ll buy the book, and maybe more than one copy. My take on my other interests in wines/spirits and cooking is that tobacco blending/processing is more difficult than those ancient but well established arts. After all, tobacco in Western civilization (sic) has only been around since Sir Walter Raleigh, which is only a few centuries. Of course, I’m speaking to SERIOUS tobacco work, not just tossing some leaves into a jar for smoking.