Here is a BBB that appears to be hallmarked in 1876. Although having pulled this one out again, I'm a little confused by it. Simply because to me I would think it was later based on style, style of the case etc. I will try and look into the 'Sharman's Patent'.

Despite appearances I suspect the pipe might date from 1901 for the following reasons. First there is evidence to suggest the shape of the Birmingham date letter cartouche varied over this period, and that therefore a round cartouche does not automatically mean 1876:

Second, I believe the introduction of the BBB "Own Make" line dated from around the mid 1880s. See this item published in Tobacco in late 1888:

Third, the earliest reference I've so far found to the Carlton (which was exclusive to BBB/Frankau) is in an ad to the trade placed in the May 5, 1882 number of Tobacco (see middle of column on right-hand side of ad):

Fourth and last, I believe the patent being referred to was granted to William Horton Sharman (who for convenience sake I'll refer to as WHS), a London goldsmith, silversmith, and tobacco pipe mounter born in 1820 and died in 1891.

Note that WHS is not to be confused with his son William Edmund Sharman, who practiced the same trade and was awarded at least one tobacco pipe related patent in in late 1898.

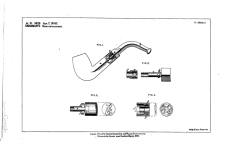

Here is WHS's patent:

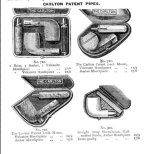

Better photographs of an actual original Carlton's tenon would settled this conjecture one way or the other. In the meanwhile see below an extract from Harrod's 1895 catalogue which features several sketches of Carlton pipes with stem separated from shank:

All of which provides a strong counter argument for a later dating of your pipe, but doesn't get to the point of being proof positive. I'd be interested to see the internals of your bulldog; in addition when I'm back in NJ I'll check my library to see if I have anything there that would help further to decide this question one way or the other.

Cheers,

Jon

Last edited: