By: John St. Mark

Wine Aromas

Wine Flavors

The label mentions "blackberry, cassis, mocha and clove." … You take a sip … it tastes like wine …

You have a good bottle of cabernet sauvignon. The label mentions "blackberry, cassis, mocha and clove." Your pinot noir is said to be reminiscent of "strawberry, rose and autumn forest earth." The chardonnay: "pear and melon, with a hint of butter." That sauvignon blanc contains "essences of citrus, passion fruit, and wild herbs."

You open a bottle, pour a glass, enjoy the beautiful color and aroma, and take a sip. It smells and tastes like… wine. Are you missing something? Where are all those flavors and aromas supposed to come from?

The descriptions may seem fanciful, but they are (or should be) based on characteristics the wine actually possesses. An ability to identify component aromas and flavors in wine is largely acquired through practice; don’t worry if they are not immediately obvious to you. If you want to, you can learn to recognize them.

Nobody is adding any fruit flavorings …

Grapes are the source of primary flavors and aromas in wine. Nobody is adding any fruit flavorings; if the wine tastes a bit like another kind of fruit, then perceptible quantities of specific chemical compounds (or precursors of those compounds, which will later release the aromatic compounds themselves) have developed in the grapes that are also found in the fruit it resembles.

a bit like another kind of fruit, then perceptible quantities of specific chemical compounds (or precursors of those compounds, which will later release the aromatic compounds themselves) have developed in the grapes that are also found in the fruit it resembles.

Just what the grapes taste like will depend on a number of factors. These include varietal characteristics (that is, the kind of grape), vineyard practices, the vintage (what happened the year the grapes were grown) and the place where they were grown. The French term "terroir" refers generally to the many features of a given place (including, but not limited to, soil and climate) that give rise to particular characteristics found in the wines produced there.

Secondary flavors and aromas are the result of winemaking, which includes fermentation and any of a number of additional processes.

The primary fermentation converts grape juice into wine. That means yeast cells metabolize sugar in the juice, releasing alcohol, carbon dioxide and energy (in the form of heat.) Variables may include the sort of fermentation vessel used, temperature, the yeast strain (or strains) involved, and how much contact the juice has with the grape skins, to name just a few; all of these factors and many others will affect the development of the wine’s flavor and aroma.

Additional processes may include aging the wine in barrels.

The porosity of the wood can influence the wine’s development significantly, allowing it to mellow and integrate, and the wine can extract flavor and aroma from the wood. Traditional barrel-making involves heating the staves around a smudge pot, thereby softening them in order to form a water-tight container. This also toasts the wood; a whole range of characteristics associated with fine wine can result from its contact with the toasted barrel. Variables may include the type and quality of wood, the degree of toast (a lighter toast can impart toasty or nutty aromas, a heavier toast can give sweet spice, coffee, chocolate, etc.), how old the barrels are (a newer barrel will impart a stronger flavor; that may be desirable in a strong wine, but could overpower the primary aromas of a lighter wine) and how long the wine is left in barrel.

The porosity of the wood can influence the wine’s development significantly, allowing it to mellow and integrate, and the wine can extract flavor and aroma from the wood. Traditional barrel-making involves heating the staves around a smudge pot, thereby softening them in order to form a water-tight container. This also toasts the wood; a whole range of characteristics associated with fine wine can result from its contact with the toasted barrel. Variables may include the type and quality of wood, the degree of toast (a lighter toast can impart toasty or nutty aromas, a heavier toast can give sweet spice, coffee, chocolate, etc.), how old the barrels are (a newer barrel will impart a stronger flavor; that may be desirable in a strong wine, but could overpower the primary aromas of a lighter wine) and how long the wine is left in barrel.

Further microbial activity can also change the wine. For example, malolactic fermentation (or "ml") occurs when lactic bacteria consume the malic acid naturally present in wine and produce lactic acid. If this happens in a controlled manner it can result in a pleasant, creamy texture and softer acidity, although spontaneous ml can make the wine cheesy and fizzy. Diacetyl, a chemical produced by malolactic fermentation, can give the wine a buttery flavor, which is very noticeable in some chardonnays. Most red wines go through ml; with whites it is a stylistic option. If the ml is suppressed the wine will retain higher total acidity and more "nerve."

Wine continues to evolve as it ages in the bottle …

Once the wine has been bottled, it will evolve more slowly. Aromas that develop as a consequence of chemical changes that occur in the bottle may contribute to what is referred to as "bouquet." Strictly speaking, discussion of bouquet (as opposed to aroma) is only applicable to older wines, but the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

changes that occur in the bottle may contribute to what is referred to as "bouquet." Strictly speaking, discussion of bouquet (as opposed to aroma) is only applicable to older wines, but the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

Wine is a complex fluid. Many chemical compounds responsible for specific flavors and aromas have been isolated and identified, and many others have not. The notes on the back label are usually based on the subjective reactions of tasters (normally they are not written by chemists) but they should reflect the wine’s physical properties.

In the column titled Wine Tasting Basics we distinguished between taste and flavor. Flavor and aroma are closely related; most of what we perceive as flavor is actually aroma in the form of volatile compounds that reach the olfactory bulb through the retronasal channel from the mouth instead of through the nose. The physiological proximity of the olfactory bulb to the frontal lobe of the brain, which stores memory, is said by some to account for the remarkable ability of certain aromas to evoke memories and emotions.

Simply try different wines and pay attention to what you smell and taste …

There are many courses and publications available that are intended to help cultivate an ability to identify and describe component aromas, but the best advice I can offer is simply to try different wines and pay attention to what you smell and taste. Give it some conscious thought and talk about it with friends who share your interest. If you’re really serious, consider writing down your impressions. As you compare wines to one another you will increasingly discern the characteristics that distinguish them.

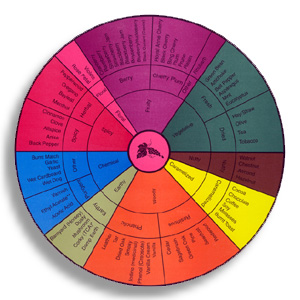

The Wine Aroma Wheel, created by Ann Noble at the University of California at Davis, is a useful tool that can help you acquire some of the standard vocabulary used by many wine professionals and enthusiasts. It consists of three concentric circles; at the center are twelve general categories such as "fruity" or "chemical," then sub-groups like "berry" or "sulfur" and finally specific aromas like "blackberry" or "skunk" (evidently, it includes undesirable aromas associated with flawed wine as well as the appealing sort you might find on a label.) Dr. Noble deliberately excludes such common descriptors as "charming" or "sophisticated"; they can be useful, but what do they smell like?

The Wine Aroma Wheel, created by Ann Noble at the University of California at Davis, is a useful tool that can help you acquire some of the standard vocabulary used by many wine professionals and enthusiasts. It consists of three concentric circles; at the center are twelve general categories such as "fruity" or "chemical," then sub-groups like "berry" or "sulfur" and finally specific aromas like "blackberry" or "skunk" (evidently, it includes undesirable aromas associated with flawed wine as well as the appealing sort you might find on a label.) Dr. Noble deliberately excludes such common descriptors as "charming" or "sophisticated"; they can be useful, but what do they smell like?

Most likely, some of the conventional descriptors will be unfamiliar to you, and you may come up with some of your own that are not part of the usual lexicon. That’s normal; each of us has our own set of references derived from our own life experience. The foods you like, the herbs and spices your grandmother used in cooking, and the flowers that grow in your area will all have aromas that resonate with you, even if you can’t name them. Many of us have a hard time identifying things we can’t see; that’s why practice and deliberate attention are called for. A set of standardized descriptors can help us understand one another better.

Analyzing aroma and flavor may not be a prerequisite for serious wine enjoyment, but if you like wine I think it will add to your pleasure and help you make good choices.

Cheers!

Great articles on wine Kevin!

I am still early in my wine journey, but the more I drink it the better I am at tasting the flavors of the wine.