On Friday, 31st May, 2024, a big thing happened: I was inducted into the Confrérie des Maitres Pipiers de Saint-Claude, along with 12 others, including my dear friend Nate King. To say this is one of the highest honors I’ve ever experienced would be a dramatic understatement. I’ve known of the Confrérie for years, but never dreamt that one day I would find myself a member of this esteemed order. Here’s the story.

Nate and I flew into Lyon on the Tuesday before the ceremony, where we were picked up by friend and pipe maker Bruno Nuttens, who had nominated and sponsored us. He drove us back to his place in the village of Charpey, where we spent a couple days with him, as well as fellow pipe maker Chris Herriot, eating, drinking, talking, listening to music, experiencing wonderful fellowship long into the night and, of course, messing with pipes in Bruno’s amazing workshop. Calling it a workshop doesn’t really do it justice; it’s almost a museum, filled with beautifully restored old machinery, vintage pipe parts, old stummels, stems, rings, and boxes of ancient pipes from long silent factories. It would take weeks to explore everything there. During those two days, Nate, Bruno and Chris did what pipe makers do. I supplied things to smoke, asked a million questions, and took photos. We all had a blast.

Thursday, we drove to Saint-Claude, pretty much the Holy Land for lovers of the briar pipe, the first of which were commercially produced there in ca. 1855. At that time, Saint-Claude already had a long history of working with wood, including making pipes from the local boxwood, but the bruyère was found to be a significant improvement. Not only was the wood more durable and relatively fire-retardant, it also presented a sweeter smoke. The pipe industry quickly grew, and by 1925, perhaps as many as 100 factories employing nearly 4000 craftsmen were producing on the order of 68-70 million pipes per year. Let that sink in for a second.

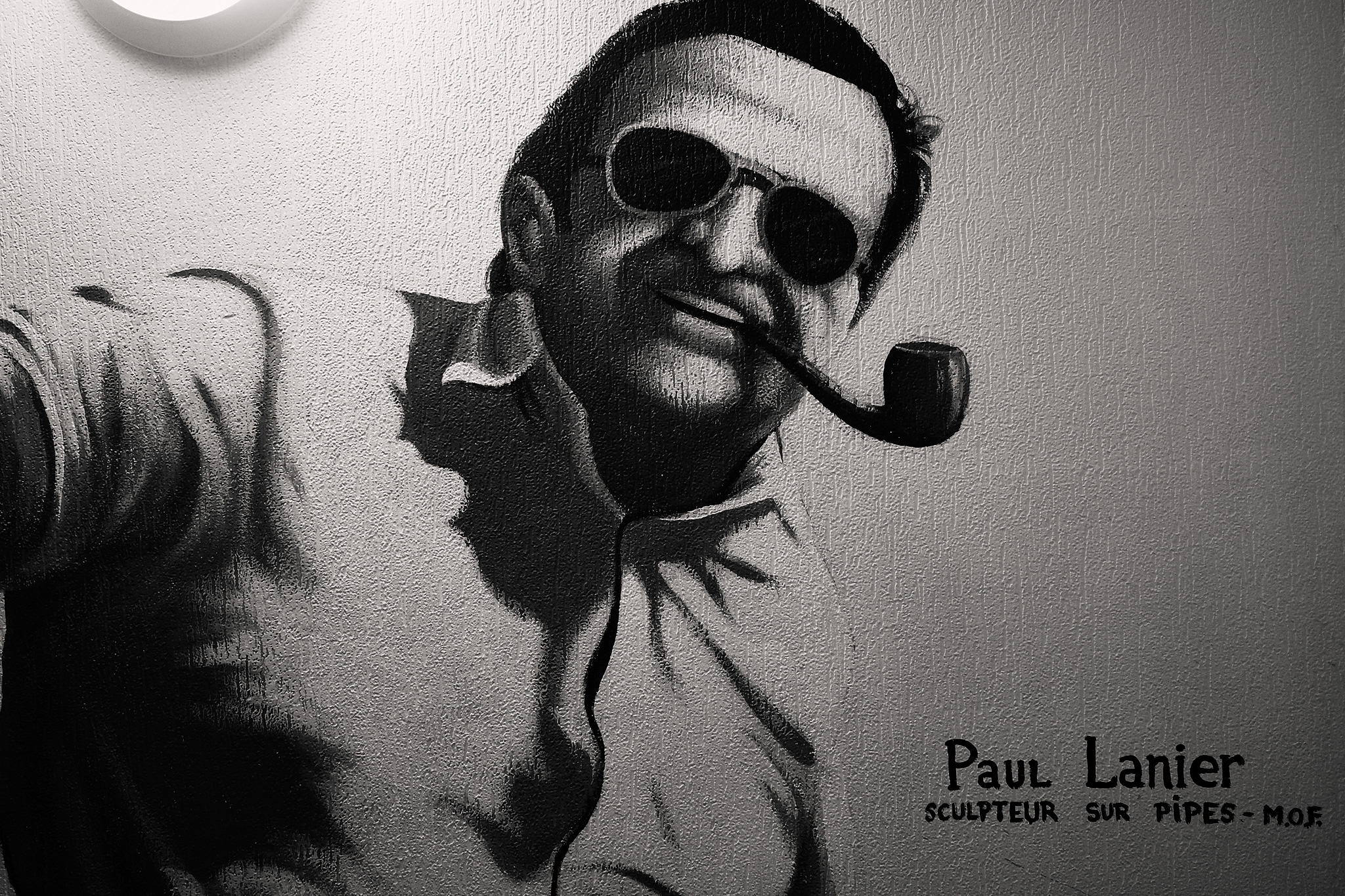

While most of those factories have long since shuttered, evidence of the importance of the pipe to the town’s history is everywhere. The rubbish bins on the street take the form of a deeply bent billiard. There are murals of pipes and pipe smokers everywhere, even on the walls of the hotel in which Nate and I were staying; on every floor, the doors of the lift would open to reveal a representation of a different, important pipe smoker. Streets are marked with round brass medallions incorporating a pipe, and there are still several pipe shops along the Place de l’Abbaye in the town center.

We spent some time at the new Chacom facility, being shown about by the ever gracious Antoine Grenard, Chacom’s owner and managing director, and also current president of the Confrérie. While modern on the outside, and efficiently laid out for pipe making, the massive building also houses a boutique, and countless boxes filled with artifacts of a very long and rich history, including hundreds of thousands of old stummels, stems and even pipes, as well as a 1956 Renault pickup, its doors emblazoned with Chacom’s logo. I could easily have spent days there exploring the ephemera, antique salesman’s samples, and everything else pertaining to the story of Chacom.

We also visited the Genod workshop in Rue Faubourg Marcel, now operated by the talented Sebastian Beaud, who demonstrated how pipes have been made there since 1865 when the shop’s machinery was powered by a water wheel. Today, Sebastian and his single employee, Jean Bouloc, produce about 2000 pipes per year on machines that, other than now being electrified, are fundamentally the same as they were nearly 160 years ago.

Evidence of old ateliers could be seen everywhere. Walls wear tattered remnants of old signage, and an old cabin that once served as storage for the town’s briar still stands. I’ve always had a strong affection for French-made pipes; my first really good one was a large, ODA sized apple by Jean LaCroix, and I’ve collected many others in the decades since. The feeling of being in the birthplace of the briar, the ancestral home of these pipes, and being surrounded by so much of the pipe’s history had a profound impact.

Finally, it was time to prepare for the ceremony. Nate and I walked, in the rain, the 100m or so from our hotel to the Musée Pipes et Diamants where the proceedings would be held. After looking around the museum for a while, which again is a place I’d like to spend many hours, we were led to the antechamber of the Confrérie’s chapter house. The room contained a large table and chairs, the walls holding glass cases housing pipes from each of the more than 1500 members accepted since the Confrérie’s formation in 1966.

After introducing ourselves, Antoine briefed us on the order of events. We would wait in the antechamber while the officers and members assembled, including my old friend (has it really been 25 years?) Tom Eltang who flew in for the event. “I wouldn’t miss this for anything!” Then, after knocking three times on the large wooden door separating the two rooms, and a suitable delay as our worthiness was deliberated, we were invited to gather in a semi-circle amongst what turned out to be rather a large group. One by one, we were presented to the assembly, and our biographies were read. In turn, we then each offered one of our personal pipes to be kept in the museum. The purpose of this pipe is symbolic, both to mark our place amongst our colleagues, and, according to Antoine, “In the hope that every member will return to Saint-Claude to visit their pipe, and to enjoy the history of this unique place.”

We then were presented with a selection of new pipes, from which we would each choose one for the next step of the induction process, the passing of the test to prove we were true pipe smokers. One by one, we were called to the central altar, where we filled our new pipe from a bronze tobacco “jar” in the shape of a head representing a Grand Master of the Confrérie, and lit it with the flame from a wooden spill handed to us by Antoine. It would be a simple enough “test” under normal circumstances, but under the watchful eyes of the assembly, I admit to a slight feeling of performance anxiety.

After all thirteen had gone through the ordeal, we again approached the altar to empty our new pipe, and leave it in on an elaborate bronze rack, after which we took our oaths, and were called in turn to the front of the chamber, where the grandmaster placed a ribbon and medallion around our necks, and “knighted” us, tapping us on each shoulder with a very large horn stemmed billiard serving as the ceremonial sword. We were presented with our certificates, and finally the ceremony was closed. It was a very dignified, formal, and lovely experience, like something out of another century. Rituals such as this are powerful, igniting and amplifying a connection both with one another, and with a connection to the currents of our deeper, collective past. It’s an experience I will never forget.

After mingling for a while in the chamber, we reconvened for a wonderful banquette of several courses. It was a time of celebration, of fellowship, and it was great to meet and chat with so many of my new brothers.

It was one of the best trips ever, and the only thing that could have made it better was if I’d been able to stay longer. As I write this, I’m aware that while my body is back in California, and my brain has finally caught up with it, jet-lag having kept it hovering over the Atlantic for a few days, a significant part of my heart remains in France.

To Saint-Claude, to my new friends and confréres, jusqu’à la prochaine fois.

–glp

|

Photos by G.L. Pease

A Very Interesting Report. Congratulations to You and Nate! You’re Very Deserving of this Prestigious Honor!

Thank you, Dave! Nearly a month ago, and I’m still wondering if it was all a dream. 😉

Greg,

Congratulations to a most worthy recipient of this honor!

Thank you so much!