Of all the modern art movements, Cubism is often considered the most difficult to wrap one’s head around. Placed properly in the scholarly context, Cubism extended out of the French avant-garde from roughly 1907 through the 1920s, and has been noted as the most influential shift in art of the 20th century. In brief, it grew from the logical progression of Cézanne’s experiments with reducing objects to form and color, and incorporated the changing attitudes of early twentieth century thought. Cubism was born to a world experiencing a period of rapid progress in science and technology—in the space of a generation, the fruits of the Industrial Revolution had yielded photography, automobiles, radio and sound recording, and airplanes. Freud began looking at the workings of the mind while Einstein explored the concepts governing the fabric of reality. Artists began to depart from the concepts of perspective and representation that had guided art since the Renaissance, embracing this brave new world.

Pablo Picasso remains the giant of the genre, predominantly associated with Cubism although he explored many different styles throughout his career. Along with Georges Braque he is credited with creating the movement, beginning with the proto-Cubist painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907. While the name Picasso is often mentioned in the same breath as Cubism, a less popularly know but highly influential practitioner of the genre was Juan Gris. A fellow Spaniard, Gris is credited with coining the term “Analytic Cubism”, the first phase of the movement that spanned the years 1910-1912.

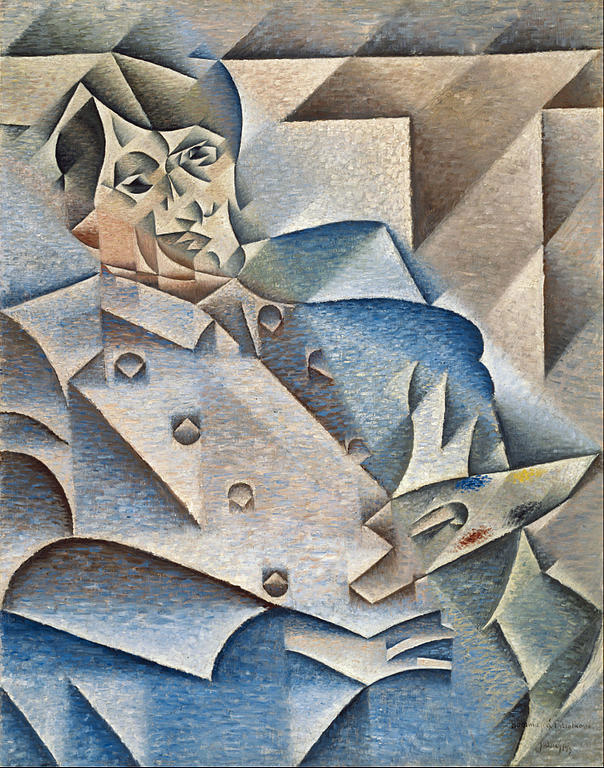

Hommage à Pablo Picasso, oil on canvas 1912

Picasso was a master of self-promotion as well as art, hence his entrenchment in popular culture. Gris was more the shy, retiring type, troubled by asthma and general ill health his entire life. While he considered Picasso a mentor and leader of the movement, the older man perhaps felt threatened by the younger’s talents, leading Gertrude Stein to note that, “Juan Gris was the only person whom Picasso wished away.” Gris’ technical skill was honed studying mechanical drawing in Madrid before moving to Paris in 1906, where he would spend the remainder of his life. This would serve him well, as the critic John Berger likened the essence of Cubism with the mechanical diagram: “The diagram being a visible symbolic representation of invisible processes, forces, structures.”

Gris was influenced heavily by the mathematical interpretation that this early Analytical Cubism espoused, and it can be easily seen in one of his seminal works, the portrait Juan Legua, on view in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Juan Legua, oil on canvas 1911

In this black & white image, the precise calculation of every brushstroke becomes apparent.

Gris actually coined the term ‘Analytical Cubism’.

What naturally caught my eye with this painting is the pipe, of course. Spending time examining it, however, what struck me was the feeling that despite the abstraction of the subject being broken up into a multitude of planes and angles, there remained somehow the true essence of a figure there. A stiff-collared gentleman, somewhat staid yet with an undeniable smirk and a twinkle in his eye, comes across quite clearly to the viewer. Unfortunately there is no photograph of the subject to compare, but I have no doubt that he would be instantly recognizable as the sitter.

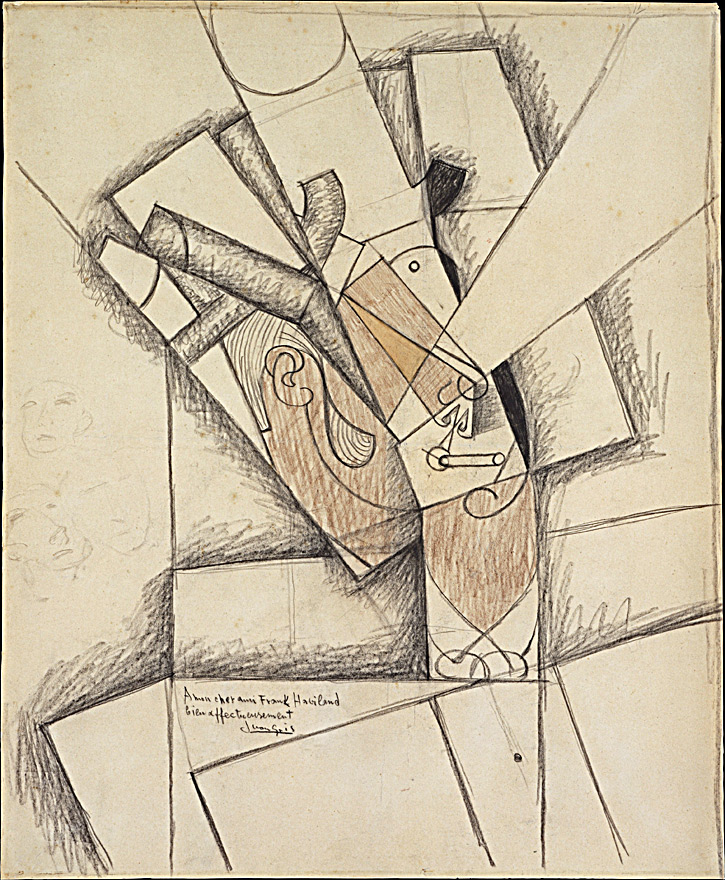

The Smoker, charcoal, crayon and wash on paper, 1913

After travelling to Céret and spending the summer with Picasso, Gris’ art makes a dramatic turn. As seen in the above study for The Smoker, the abstraction of form is much more pronounced, the shift in perspectives much more juxtaposed. Picasso’s influence is seen clearly here, yet Gris manages to take a step beyond the master with the finished painting below—note the exuberant use of color, a stark departure from Picasso’s and Braque’s more monochromatic works. The tubular shape of the cigar is repeated to an extreme, illustrating the relationship of form that is a hallmark of Cubism.

The Smoker, oil on canvas, 1913

The influences of both Picasso and Matisse are perfectly married in this still life from late 1913. In it one can see the confluence of Matisse’s color planes with the Cubist deconstruction of form—as well as another pipe.

Still Life with a Guitar, oil on canvas, 1913

Yes, Juan Gris enjoyed his tobacco immensely, both in pipes and cigars, and you can see his passion in the paint. Tobacco was of course very much in vogue in the beginning of the twentieth century, yet more than many of his contemporaries he included the accouterments of smoking—pipes, cigars, cigarettes, even tobacco pouches and packets—in his still lifes. Used as a recurring motif, pipes and tobacco lend a rustic, down-to-earth charm; they are practically trademarks of a Gris still life. Importantly, they serve as a visual cue that virtually everyone could relate to in what could otherwise be rather abstruse compositions.

The recognition of the synthetic nature of painting—that a representation of an object was not in fact the object—had astounding impact, first truly realized in Cubism (and later solidified with Magritte’s Treachery of Images). This radical notion of portraying all angles of an object simultaneously was at the crux of the shifting perceptions in science as well as art in the early twentieth century. In Cubism lies also the theory of relativity, as well as Freud’s inspections of dream and consciousness, in that the viewer’s perception of an object is more than a single perspective; the representation of the object is a culmination of the combined perceptions of many angles and times, fused in observation and memory. It is the total object, in all our ways and moments of viewing it, translated simultaneously onto the picture plane. While somewhat esoteric in concept, in practice one can begin to feel a painting’s subject as clearly as a more standard representational work. In Gris’ own words,

“I work with the elements of the intellect, with the imagination. I try to make concrete that which is abstract. I proceed from the general to the particular, by which I mean that I start with an abstraction in order to arrive at a true fact.”

Book, Pipe and Glasses, oil on canvas 1915

Bottle, pipe and Playing Cards, oil on canvas 1919

Pipe and Pack of Tobacco, oil on canvas 1922

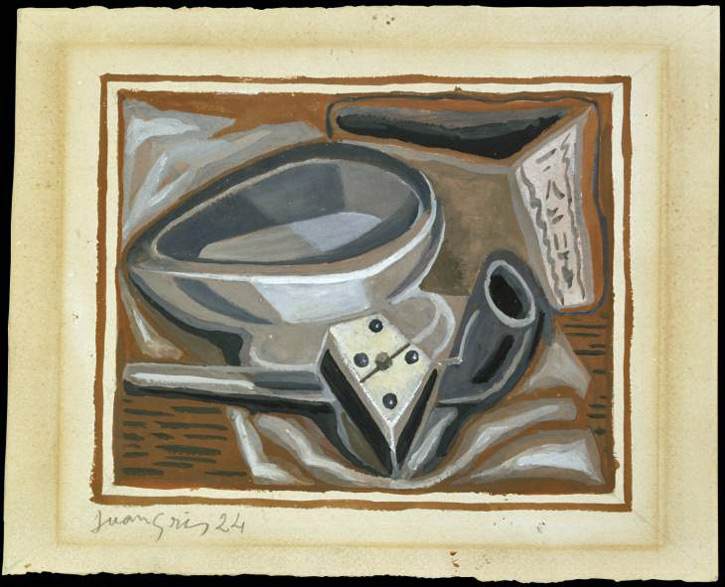

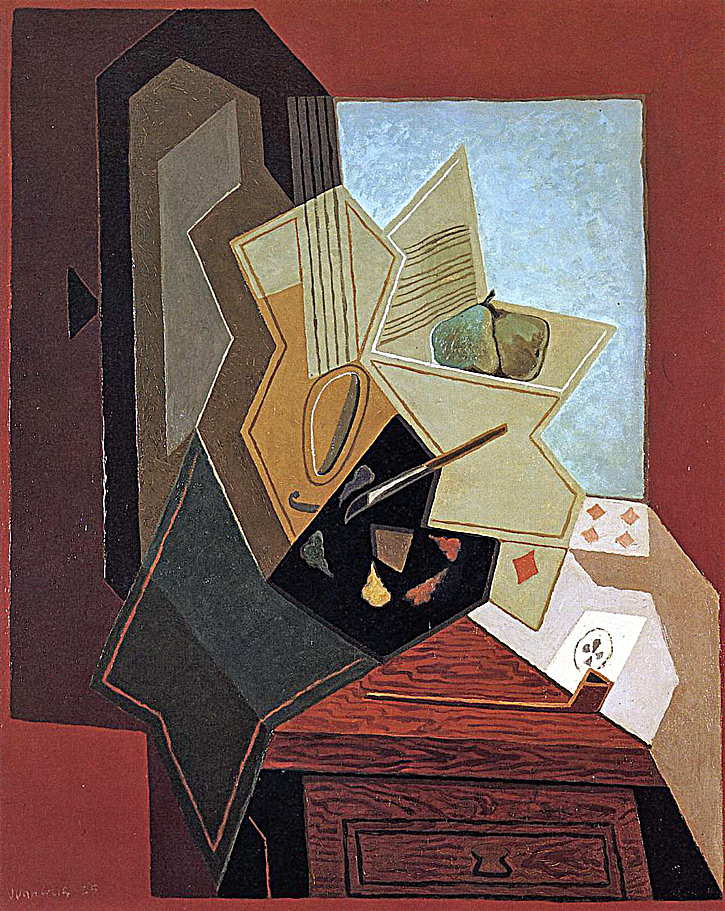

Gris’ painting began to develop into a very personal style after 1915, and his later work became unmistakably his own. The early Analytic Cubism had become Synthetic Cubism, influenced heavily by the collage techniques pioneered by Picasso. Times were tough during the war years, and he and his family lived in poverty. The pipe and cigar appear frequently in his works, and serve as a humanizing motif, easily recognizable and commonplace items that ground the wild abstractions into reality. The pipes are often unmistakably of the clay “tavern pipe” variety, further reinforcing the rustic theme. It’s easy to imagine Gris, with barely enough money scraped together to afford paints and tobacco, seeking solace in pigments and pipe.

Pipe and Domino, gouache on paper 1924

José Victoriano Carmelo Carlos González-Pérez changed his name to the modest, almost surreptitious, Juan Gris when he moved to Paris at age nineteen. The thirteenth son of a once wealthy family that had fallen on hard times, he sold all his possessions to pay the fare to Paris, incidentally revoking his Spanish citizenship in the process—he had left without a passport and without his compulsory military service, branding him a fugitive and preventing him from ever returning to his homeland. He succeeded as an artist in his lifetime, making a modest living and eventually going on to present an influential lecture at the Sorbonne entitled “On the Possibilities of Painting”. His passion and dedication to his art helped define Cubism, and I like to think that his pipe smoking contributed to this in no small part. Sadly, his always-precarious health worsened after the autumn of 1925, and he died in Boulogne-sur-Seine on 11th May, 1927, at the age of forty. We are left with more than six hundred paintings, and a legacy that changed art forever.

The Painter’s Window, oil on canvas 1925

Special thanks to Sabine Rewald, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Cynthia Iavarone, Collections Manager, both of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wonderful survey of Juan Gris. Not a household name to me but unforgettable now. Thanks for the research and for posting these lovely pieces. Keep ’em coming Mr. Roberts!

As an art teacher, I must say I LOVE this article.

How wonderful to be shown fine art along with the fine art of pipe/tobacco smoking!