Jesse's post ^^^^ triggered a search on my computer for something I wrote about Scottie a while back that goes into greater depth about her motivation, philosophy, etc.

Found it.

Since P&T magazine is no more I doubt I'll get in too much trouble for sharing it here.

It's a story that Chuck Stanion asked me to write for P&T magazine in the summer of 2016. It ended up running as the feature as seen here (with added photos, of course).

==================================================

When watching Scottie Piersel work on a pipe the first thing you notice is the intensity of her gaze. Somewhere between a Japanese

shokunin perfection-chaser and a bird of prey, she never stops

looking, searching for things that aren't quite right, checking against a backlight, glide-touching with a fingertip, then cutting or sanding a little. Then doing it all again.

"You certainly concentrate, don't you?" I say. She returns to the moment at the sound of my voice, looks at me with a huge smile, and laughs. "Maybe. I guess so. I lose track of time, that's for sure."

"Since this is an interview I must ask if it has always been like that? This relaxed intensity of yours?"

She thinks only long enough to form the first word. "Yes. I literally grew up in an artisan environment---a family-owned auto body shop that did metal finishing, not just replaced panels---and my grandfather didn't fool around. He brought every sense he could into his work. Used his hands, eyes, and ears, and said he only had to watch someone for a minute to know how their project would turn out. It stuck with me."

Suddenly there's silence. I look up. "Will that be in there?" she asks. "What I said just now about my grandpa?" I assured her it would. She smiles.

"So, when did pipes come into your life?" I ask. "A young woman's life, at that. Pipes are not exactly common these days."

"It was straightforward, actually," she says. "My husband loves good cigars and one day just decided to give pipe smoking a try. He bought a couple along with some tobacco and seemed to like it, so when Father's Day came around I went online to buy him another as a gift. When I came across a do-it-yourself kit---you know those pre-drilled blocks?---I thought my actually making him one might make it more special."

"Nice. How did it go?"

The sunshine smile again. "Well, it wasn't very pretty, but you could smoke it. He

did smoke it. And making it was fun, so I bought another kit and it turned out better. Then another. Then I got a lathe, started using un-drilled wood, met other carvers online, started sharing tips and tricks... and, well... here we are."

There we were, indeed.

Only a few weeks before this conversation, Scottie had entered the Kansas City Pipe Club's annual North American Pipe Carving Contest, and handily placed in the winning 7-day set. Not easy to do, especially since it was one of the contest's ruthlessly strict "classic years" where fractions of a millimeter and attention to the smallest detail can make the difference between being selected for the set or not. That she had done it with an Author, a massive, chunky, flowing shape that was the polar opposite of the smallish, double-take-inducingly-slender geometric design that was her specialty, only added to the intrigue.

"Tell me about giving the recent Kansas City carving contest a go. Are you a competitive person by nature, or did you just feel it was something that might be educational or otherwise interesting?"

Again no hesitation. "I'm

extremely competitive. My mom says I was born that way. Doesn't matter what it is, I try to be the best. Else why bother?" Then she softens. "Sorry. I didn't mean to imply I like glory or attention. I compete for

myself. There's no other way to know how good or bad you really are at something, right? Your family and friends will always blow sunshine at you, and so will your own ego if you let it... So going head-to-head with other people is the only way to really know."

"I agree," I said. "Did the pressure of facing that truth affect how you made your entry? Such as easing into it in an experimental way that involved lots of practice attempts, maybe, or the opposite of that---deliberately waiting until the last minute because working without a safety net brings out something special in you?"

"Oh, gosh. Nothing like that. One day maybe I'll have that much confidence, but certainly not now. I definitely took the first path. In fact, the KC contest people announce the upcoming shape almost a year in advance, so I took full advantage of the time to study the Author shape family and make a few. The one I entered was my fourth or fifth, I think."

"Did you do anything differently once you knew you were holding your 'entry specimen'? When you realized that the perfect concave curve you had been chasing---or whatever it was---and a sufficiently flawless block of briar had finally converged?"

That smile again. "Nothing different in terms of tools, techniques, or finishes, but I did do something that Bo Nordh was famous for, which was to slow things down at that point and do the final shaping in tiny steps. That every time I thought it was done, no matter how certain I was, I forced myself to put the pipe on a shelf out of sight for the rest of the day. Then, the next morning I'd pick it up again and examine everything with a fresh eye. It was amazing. Bo was right. Easily one of the most important things I've learned about pipe making so far: when you're tired and want to be finished with a particular one, your brain lies to you. It edits and distorts things so you'll be satisfied. When perfection is your goal, though, you have to ignore that editing and distortion until everything truly

is spot-on."

"How do you know when you really

are finished, then? When 'truly spot-on' is reached?" I asked.

"When there are no tape dots for three days." She said.

"Please explain."

"That's how I mark the high spots. Tiny tabs of green masking tape. When I saw a high area, I'd sticker it. After all the high areas were marked I'd level them with sandpaper or a file until they were about ninety percent gone. Then put the pipe away. The next day I'd do it all again, and the next, until no high spots remained. For the contest pipe I made extra sure by not moving on to finishing until there were no tape dots for three fresh-eyed days in a row."

"Judging by the contest results, I'd say you got 'em all." I said.

She smiled.

"Come to think of it, strictly speaking, 'removing all the high spots' applies to the entire process of shaping a pipe starting with the entire briar burl coming out of the ground, doesn't it? Since carving is material removal by definition---unlike creating an object with clay where material can be added---you must train yourself to see shaping things in a subtractive way. Recognize how to smooth and balance the flow of curves and shapes and still have everything line up, by only by

taking away from them."

"Exactly," she said. "The tool sequence is bandsaw, lathe, high speed spinning disks, files, sandpaper, and buffer. Plus a few drills along the way, and maybe a chisel or two depending on the shape."

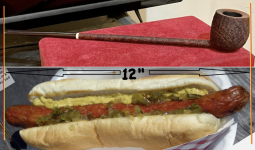

"What sort of dimensional changes are we talking about during that final 'Bo Nordh' fine-tuning process you described?"

"Gosh. I'm not even sure how that could be measured. No more than a few thousandths of an inch, I imagine. But seeing things that small isn't hard with practice. Just dim your shop lights and shine a lamp on a section of smooth, white wall. Holding a dark pipe in front of a bright background like that lets you see its profile like nothing else. Then, when the profile finally looks right from every angle, hold the pipe under a bright light and move it around to catch any low-angle shadows on the wood that shouldn't be there, and to create reflections on the stem. Those shadows and reflections expose

everything."

"As long as we're talking about the Kansas City contest, how did being one of the winners rate on your Pipemaking Memories list?" I ask. "For that matter, what is your best pipe-related memory of any kind?"

Only a second's pause. "There are two, and it's a tie. Getting in the seven day set is one of them. One of those 'made it to the top of the mountain' kind of memories. Achieving a goal. The other is the long weekend I spent at the Chicago show a few months ago. It was my first time and it was like Disneyland. The people I met, the things I saw, the things I learned, the special moments I shared. It was all good. One hundred percent good."

I couldn't help but smile and laugh a bit myself. "Yeah, that's pretty much how it is for everybody. The Force is strong there, isn't it?."

We were both quiet for a second when we realized my joke actually had the feel of truth.

I shook it off and continued. "You did well there commercially, too, I understand. Had a table and sold a lot of pipes?"

"Yes," she said. "I arranged to share a table with a friend and did pretty well for a first-timer. I had no idea what to expect, so just took every pipe I had on hand that wasn't spoken for, and hoped for the best. When someone in the smoking tent bought a fourth of them on Thursday evening before the show even started I was pretty happy. It meant the trip would be a success for me money-wise, sure, but a much bigger reason was because of how experienced and sophisticated the buyers are at Chicago. Making pipes that those guys liked enough to actually buy as a batch felt like hitting a double off a Major League pitcher my first time at bat."

I must have looked surprised, because she said, "Yes, I'm a completely and absolutely hopeless big time sports fan, so don't even go there."

"Yes ma'am!" I said.

She laughed.

(Like those kids who appear in the music world every now and again that can play classical piano or violin at a professional level while still in grade school, talent shows up early.)

(Like those kids who appear in the music world every now and again that can play classical piano or violin at a professional level while still in grade school, talent shows up early.)