For decades, there have been two urban legends orbiting around the Dunhill trademark dot.

One is that they are made out of ivory. They are not. The material used since day one is something called celluloid, which is an early-days plastic.

The other urban legend is that they used some sort of black material (I've heard everything from black pearl to obsidian) for special pipes made to order for famous people, dignitaries, and so forth. That isn't true either.

Recently I received a 1922 Shell with a black dot whose owner was aware the black dot business was romantic silliness (and also knew its actual cause), and wanted his pipe to look the way Dunhill intended---as in, actually sent out their door in 1922, and also for the first years of its life.

What IS the actual cause?

Over-drilling the hole for the dot at production time until it intersected the DRAFT hole, which resulted in all that lovely black crud you see on the end of a used pipe cleaner being stuffed into the dot hole from "underneath", and the microscopically sponge-like celluloid absorbing and wicking it upward until the dot gradually darkens to pure black.

Ironically, the only way to make a 102 year-old Dunhill dot LOOK like it's made from celluloid, though, is to make it out of ivory.

Why? Because celluloid degrades slightly in a beautiful way as it ages: It becomes ever-so-faintly ivory in color as well as faintly translucent. (It's gorgeous. A patina that some collectors refer to as "milky")

So, here is the time machine process, step by step.

The single biggest hazard is drilling out the old dot absolutely exactly, without being off-center even a couple ten-thousanths of an inch, because missing will result in an OVAL hole. A mistake that has no re-wind button.

Another fussy business is fashioning a new "dot rod" from ivory (NOT elephant ivory, but walrus tusk ivory which is completely legal), because it must be cut down to an exact snug/slip-fit in the hole. Doing that requires either a jeweler's lathe (a pipemaker's lathe won't hold a workpiece so small), or doing it by hand with a belt sander and electric drill.

There is a re-wind button if you screw up the new dot rod---just keep trying until you get it right---but holding under a half-thou by hand sure is entertaining for anyone who doesn't know the tricks involved.

----------------------------------

The original, tar-blackened celluloid dot ----

A "center mark" made with a needle-point etching tool (necessary because finding center from an oblique view is impossible) ---

Clamping the stem, then aligning the center mark via x-y table ----

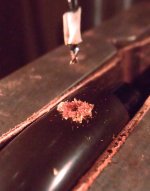

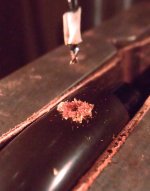

Drilling out the old dot. Notice the shavings aren't black... the celluloid only turns black on the topmost surface where the "upward flow of crud" stops and collects ----

The new hole ----

Walrus tusk ivory as supplied to people who do stuff with it (jewelry makers, etc.) ----

A sawn-off splinter of it chucked in a drill a ground into a rod ----

The ivory glued into the new hole ----

The ivory cut off, leveled, and polished ----

One is that they are made out of ivory. They are not. The material used since day one is something called celluloid, which is an early-days plastic.

The other urban legend is that they used some sort of black material (I've heard everything from black pearl to obsidian) for special pipes made to order for famous people, dignitaries, and so forth. That isn't true either.

Recently I received a 1922 Shell with a black dot whose owner was aware the black dot business was romantic silliness (and also knew its actual cause), and wanted his pipe to look the way Dunhill intended---as in, actually sent out their door in 1922, and also for the first years of its life.

What IS the actual cause?

Over-drilling the hole for the dot at production time until it intersected the DRAFT hole, which resulted in all that lovely black crud you see on the end of a used pipe cleaner being stuffed into the dot hole from "underneath", and the microscopically sponge-like celluloid absorbing and wicking it upward until the dot gradually darkens to pure black.

Ironically, the only way to make a 102 year-old Dunhill dot LOOK like it's made from celluloid, though, is to make it out of ivory.

Why? Because celluloid degrades slightly in a beautiful way as it ages: It becomes ever-so-faintly ivory in color as well as faintly translucent. (It's gorgeous. A patina that some collectors refer to as "milky")

So, here is the time machine process, step by step.

The single biggest hazard is drilling out the old dot absolutely exactly, without being off-center even a couple ten-thousanths of an inch, because missing will result in an OVAL hole. A mistake that has no re-wind button.

Another fussy business is fashioning a new "dot rod" from ivory (NOT elephant ivory, but walrus tusk ivory which is completely legal), because it must be cut down to an exact snug/slip-fit in the hole. Doing that requires either a jeweler's lathe (a pipemaker's lathe won't hold a workpiece so small), or doing it by hand with a belt sander and electric drill.

There is a re-wind button if you screw up the new dot rod---just keep trying until you get it right---but holding under a half-thou by hand sure is entertaining for anyone who doesn't know the tricks involved.

----------------------------------

The original, tar-blackened celluloid dot ----

A "center mark" made with a needle-point etching tool (necessary because finding center from an oblique view is impossible) ---

Clamping the stem, then aligning the center mark via x-y table ----

Drilling out the old dot. Notice the shavings aren't black... the celluloid only turns black on the topmost surface where the "upward flow of crud" stops and collects ----

The new hole ----

Walrus tusk ivory as supplied to people who do stuff with it (jewelry makers, etc.) ----

A sawn-off splinter of it chucked in a drill a ground into a rod ----

The ivory glued into the new hole ----

The ivory cut off, leveled, and polished ----