By C. R. S. Lyles

All Ralphie Parker wanted for Christmas was "an official Red Ryder carbine-action 200-shot range model air rifle with a compass in the stock, and this thing which tells time." However, as those who are already familiar with the story know, one thing stands in his way of acquiring this coveted possession: his mother’s resounding mantra of "You’ll shoot your eye out."

All Ralphie Parker wanted for Christmas was "an official Red Ryder carbine-action 200-shot range model air rifle with a compass in the stock, and this thing which tells time." However, as those who are already familiar with the story know, one thing stands in his way of acquiring this coveted possession: his mother’s resounding mantra of "You’ll shoot your eye out."

The similarities between the conflict of A Christmas Story and the conflicts that smokers encounter and have encountered with health care crusaders, anti-smoking activists, and the majority of the non-smoking population in general illuminates a startling parallel which can best be seen through public health’s claims that smoking-related deaths are comparable to Nazi genocide and a 1986 Journal of the American Medical Association editorial which has dubbed the last half-century "the tobaccoism holocaust".

The irony of these claims, of course, is that Adolf Hitler was an rabid anti-smoker, going so far as to order that Joseph Stalin’s cigarette be removed from an official photograph taken after the signing of the Germany/Soviet Union nonaggression pact.

But irony in and of itself is what has come to define the anti-smoking crusade. In public, their pointed posturing and vehement calls for the end of the tobacco luxury rival even the most enthusiastic televangelist. In private, their desire for the money generated from the sale of tobacco products would put the fictional character of Gordon Gekko to shame.

Sadly, the argument over whether or not people should be allowed to smoke has become a nearly all-consuming issue in today’s society, shadowing while at the same time enhancing other timely and equally dichotomous issues like the same-sex marriage debate, stem cell research, and the pro-life vs. pro-choice battle.

However, unlike those other arguments, the confrontation between smokers and non-smokers has a history that goes back over four hundred years.

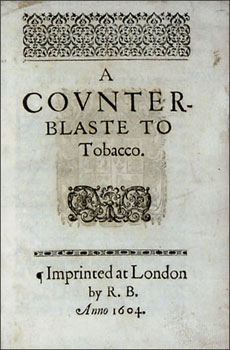

In 1603, King James I published A Counterblaste to Tobacco, which can be considered the first piece of anti-smoking propaganda. In it, James asks "Shall we…abase ourselves so farre, as to imitate these beastly Indians?…Why doe we not as well imitate them in walking naked as they does?…yea why doe we not denie God and adore the Devill as they doe?"

In 1603, King James I published A Counterblaste to Tobacco, which can be considered the first piece of anti-smoking propaganda. In it, James asks "Shall we…abase ourselves so farre, as to imitate these beastly Indians?…Why doe we not as well imitate them in walking naked as they does?…yea why doe we not denie God and adore the Devill as they doe?"

James, of course, speaks of the traditional Native American practice of smoking tobacco, whose luxury the first of the American settlers would discover and eventually cultivate into an industry beginning in the second colony of Virginia (a village which was, ironically, named Jamestown).

James I was the first person to use such excessive language in an attempt to dissuade smoking, but he was by no means the last. He also set a precedent which has come to define the anti-smoking agenda in 1619, when he forbade domestic cultivation of tobacco and made the trade a royal monopoly, thus rejecting smoking but welcoming the money it generated.

The lesson to be learned from the anecdote about James I and, by extension, Ralphie Parker, is that of choice, because in both circumstances the dreams, desires, and ambitions of the few are blasted by some form of authoritarian leadership who believes that it has the best interests for the few at heart.

As stated in the book For Your Own Good: The Anti-Smoking Crusade and the Tyranny of Public Health, author Jacob Sullum illustrates this point beautifully:

"The accumulation of evidence through systematic research – especially large-scale epidemiological studies that examined the relationship between smoking and diseases that take decades to develop – elevated warnings about tobacco above anecdote, folklore, and superstition. It gave tobacco’s opponents new credibility and added to their ranks. But it did not, by itself, indicate what the government should do about smoking, if anything. That is why Americans are still arguing about what, exactly, ‘appropriate remedial action’ is."

We get it; smoking is bad for us. We understand the risks inherent in taking a drag, and we are adult enough and mentally cognizant enough to be able to weigh the pros and cons.

Even before Congress adopted the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984, we knew the warnings.

It has been argued that the warning labels on tobacco products are for those who "are not" aware of the potential risks, but you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone who doesn’t know that smoking is possibly dangerous. Even with the cleverly-rotating reminders that are always preceded by the garishly-capitalized SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING, the message is understood even before it is read.

It has been argued that the warning labels on tobacco products are for those who "are not" aware of the potential risks, but you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone who doesn’t know that smoking is possibly dangerous. Even with the cleverly-rotating reminders that are always preceded by the garishly-capitalized SURGEON GENERAL’S WARNING, the message is understood even before it is read.

And while it can be argued that the general concern exhibited by the anti-smoking activists is somewhat flattering, it can become a little bit smothering. Like an overbearing matriarch, the incessant molly-coddling of these health care crusaders comes off as more annoying than good-hearted, especially when the money generated from tobacco sales is in fact funding their vendetta against the very people whom they seek to save from themselves.

In fact, it is this ceaseless posturing which has turned off more potential supporters than anything else. In his article "The Triumph of the Cigarette", Carl Avery Werner writes that "The more violently [the cigarette] has been attacked, the more popular it has become", due primarily to the "melodramatic" propaganda cultivated by the more zealous of tobacco’s opposition.

And if any evidence is needed regarding the bizarre and somewhat controversial depths to which the anti-smoking activists will stoop in order to achieve their goals, one only has to look at the research conducted on mice in which scientists knowingly coated their backs with tar in order to simulate the effects which lead to the development of cancer.

As it is expressed by the narrating voice of Guy Ritchie’s film RocknRolla, "We all like a bit of the good life." Some of us like to smoke. Some of us like to tell other people not to. The point is, the probability of a smoker purposefully walking up to you and blowing smoke is your face is slim, whereas the probability of an anti-smoking activist coming up to you and refusing to leave you alone while they espouse all the "scientific evidence" against your "disgusting habit" lingers somewhere between 99-100% probable.

And while we are humbled by your concern for our well-being, we’re honestly kind of tired of hearing about how we’ll shoot our eye out.

Carter R. Lyles is a student at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, FL and at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He is a journalism/psychology major, and in addition to his work at Pipes Magazine, he has contributed articles to The Alligator, Thursday Night Magazine, and The Fine Print. |

The point is clear, and the argument very nicely accomplished. Excellent writing.

Great article. Nazi anti-smokers are everywhere. I believe they inhale more toxic exhaust from their cars than they do from our smoke, yet they blame us for all the lung cancer.

Very well done. Thank you.