Because having "a fill" in a briar pipe meant only one thing from the earliest days of briar pipe manufacturing until the 1970's/1980's---over a hundred years---the inertia (for lack of a better term) of the word is strong.

It means that a non-briar material has been added to fill small dents, holes and cracks on stummels before they are finished, the same way a dentist repairs a decayed tooth by cleaning and shaping the decayed area's walls with small tools, then fills the void with gold, silver, or dental epoxy.

(The material used for briar pipes is called mastic, btw. It's a clay-like putty that hardens and has been used for centuries in woodworking.)

Why weren't those flawed stummels sandblasted, you ask? Because sandblasting didn't exist for the first fifty(ish) years that briar pipes were mass produced, and only caught on relatively slowly after it was invented. For a long time, the only "proper" pipe in the mind of the Western world was a smooth one.

That being the case, the only thing manufacturers COULD do since briar's natural state is a mass of tangles and knots rife with inclusions and gaps, was have a table of "briar dentists" the end of the shaping line giving the bowls "dental fillings" of mastic putty.

The percentage of pipes that did not require some degree of attention was small, and the percentage that were literally defect free---meaning not even sand specks---was negligible. Such is briar.

Then came the latter(ish) third of the 20th century and what we now call artisan carvers. Pipe sculptor-artists who used high grades of briar, and could carve stummels that accommodated a block's shape and internal grain layout.

Such accommodation didn't solve the flaw problem completely, though, since all briar has flaws. It only reduced it. Grading their output by flaw severity and count was still required. (Mastic putty was never used by any of them, btw. It's easily detected, associated with volume-oriented factories, lower quality pipes, etc.)

Making a stummel look as good as possible absolutely is the name of the game, though, because the higher the grade the higher the price.

So, what technique did they develop to maximize a stummel when it came to grading?

They leveraged a fundamental truth about wood. That it's fibrous and textured by nature, and cannot be made truly smooth---meaning shiny-smooth---without covering it with several sanded-almost-off, then re-applied and sanded-almost-off-again layers of a clear coating. (All kinds of stuff from shellacs to hardening oils are used. Every artisan carver has his favorites.)

They are filling the surface's low spots, you see, a few ten-thousandths of an inch at a time.

Then, when all of the low spots have been filled to level, a final coat is applied and dries completely smooth.

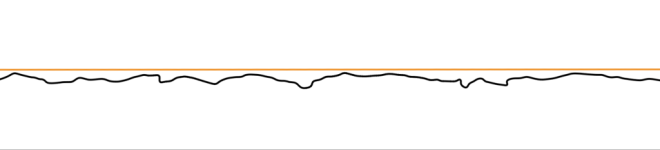

Here's a greatly magnified side-view, diagram-style ---

It didn't take long for the high grade carvers to realize that some flaws (the pepper-speck ones, and then only up to a certain size) could be removed dentist-style, and the resulting micro-cavity spot-filled in advance with the same kind of transparent material that was going to be applied to the entire pipe anyway.

Doing that had exactly the same end result as coating and sanding the entire pipe, say, six or seven times (where all of the finish except those spots would be removed by sanding), reduced to two or three times.

Sad aside: Decades ago, a famous name carver admitted doing the micro-cavity-spot-filled-in-advance procedure---something which is considered routine by every carver I've ever known---and has paid for it ever since, Salem Witch Trial style.

The accusation? "Carver X uses fills!!!"

Consumers insisting on simplified black-or-white / yes-or-no answers to questions that are not simple, plus humans in general loving tabloid-style scandal did the rest. (The pushback continues to this day, believe it or not)

Anyway, that's it.

All fills are not created equal (so to speak), and knowing what's what might come in handy for you someday.

It means that a non-briar material has been added to fill small dents, holes and cracks on stummels before they are finished, the same way a dentist repairs a decayed tooth by cleaning and shaping the decayed area's walls with small tools, then fills the void with gold, silver, or dental epoxy.

(The material used for briar pipes is called mastic, btw. It's a clay-like putty that hardens and has been used for centuries in woodworking.)

Why weren't those flawed stummels sandblasted, you ask? Because sandblasting didn't exist for the first fifty(ish) years that briar pipes were mass produced, and only caught on relatively slowly after it was invented. For a long time, the only "proper" pipe in the mind of the Western world was a smooth one.

That being the case, the only thing manufacturers COULD do since briar's natural state is a mass of tangles and knots rife with inclusions and gaps, was have a table of "briar dentists" the end of the shaping line giving the bowls "dental fillings" of mastic putty.

The percentage of pipes that did not require some degree of attention was small, and the percentage that were literally defect free---meaning not even sand specks---was negligible. Such is briar.

Then came the latter(ish) third of the 20th century and what we now call artisan carvers. Pipe sculptor-artists who used high grades of briar, and could carve stummels that accommodated a block's shape and internal grain layout.

Such accommodation didn't solve the flaw problem completely, though, since all briar has flaws. It only reduced it. Grading their output by flaw severity and count was still required. (Mastic putty was never used by any of them, btw. It's easily detected, associated with volume-oriented factories, lower quality pipes, etc.)

Making a stummel look as good as possible absolutely is the name of the game, though, because the higher the grade the higher the price.

So, what technique did they develop to maximize a stummel when it came to grading?

They leveraged a fundamental truth about wood. That it's fibrous and textured by nature, and cannot be made truly smooth---meaning shiny-smooth---without covering it with several sanded-almost-off, then re-applied and sanded-almost-off-again layers of a clear coating. (All kinds of stuff from shellacs to hardening oils are used. Every artisan carver has his favorites.)

They are filling the surface's low spots, you see, a few ten-thousandths of an inch at a time.

Then, when all of the low spots have been filled to level, a final coat is applied and dries completely smooth.

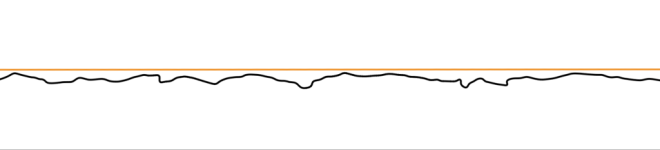

Here's a greatly magnified side-view, diagram-style ---

It didn't take long for the high grade carvers to realize that some flaws (the pepper-speck ones, and then only up to a certain size) could be removed dentist-style, and the resulting micro-cavity spot-filled in advance with the same kind of transparent material that was going to be applied to the entire pipe anyway.

Doing that had exactly the same end result as coating and sanding the entire pipe, say, six or seven times (where all of the finish except those spots would be removed by sanding), reduced to two or three times.

Sad aside: Decades ago, a famous name carver admitted doing the micro-cavity-spot-filled-in-advance procedure---something which is considered routine by every carver I've ever known---and has paid for it ever since, Salem Witch Trial style.

The accusation? "Carver X uses fills!!!"

Consumers insisting on simplified black-or-white / yes-or-no answers to questions that are not simple, plus humans in general loving tabloid-style scandal did the rest. (The pushback continues to this day, believe it or not)

Anyway, that's it.

All fills are not created equal (so to speak), and knowing what's what might come in handy for you someday.