Martin Hunter

Tucked away on the third floor of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue are two Georgian-style, pine-paneled rooms, resembling those of a country manor house – which indeed they once were – that contain the finest array of tobacco-related material in the world: The George Arents, Jr. Collection.

Tucked away on the third floor of the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue are two Georgian-style, pine-paneled rooms, resembling those of a country manor house – which indeed they once were – that contain the finest array of tobacco-related material in the world: The George Arents, Jr. Collection.

Once you’ve made your way through the long, cabinet-walled reading room, you can sink into a cozy sofa near a fireplace which bears an engraved motto by Edward Bulwer-Lytton: “The man who smokes, thinks like a sage and acts like a Samaritan.” Over this Georgian mantle hangs a painting by the poet e.e. Cummings, of a pipesmoker. Thus comfortably seated, one has an urge to light up a pipe oneself (not allowed), take a sip of an ice-cold martini (not offered), and ask the curator of the Arents collection, Virginia Bartow, who was this major collector, and why did he choose tobacco for his subject?

“George Arents came from a multigenerational Virginia tobacco-growing family, whose firm was one of the founding members of the American Tobacco Company,” explains Bartow. Arents initially worked with the family firm, eventually patenting cigarette- and cigar-rolling machines, which he went on to manufacture and which eventually produced two thirds of the cigars smoked in this country. He moved from Virginia to New York, where his company had its headquarters and, in time, built an estate, ‘Hillbrook,’ in suburban Westchester County.

In 1893, as a young man of 17, while browsing in an antique bookshop, Arents purchased a pamphlet titled “A Pinch of Snuff,” for $2.25. This first purchase lit up – if you will – what was to become a burning passion for tobacciana, which continued throughout his life. Fascinated by all aspects of tobacco, Arents went on to collect not only books, but any item related to tobacco that appealed to his imagination and fancy. Shortly after his initial purchase, he bought a very rare and expensive volume published in 1507, Cosmographiae Introductio, which was written by Martin Waldesmuller, a young teacher in eastern France, who cites an account of explorer Amerigo Vespucci’s having observed Native Americans chewing a certain green plant. “This book remains the earliest printed reference to tobacco, and the year 1507 became for Arents the starting point of his collection,” explains Bartow.

In 1893, as a young man of 17, while browsing in an antique bookshop, Arents purchased a pamphlet titled “A Pinch of Snuff,” for $2.25. This first purchase lit up – if you will – what was to become a burning passion for tobacciana, which continued throughout his life. Fascinated by all aspects of tobacco, Arents went on to collect not only books, but any item related to tobacco that appealed to his imagination and fancy. Shortly after his initial purchase, he bought a very rare and expensive volume published in 1507, Cosmographiae Introductio, which was written by Martin Waldesmuller, a young teacher in eastern France, who cites an account of explorer Amerigo Vespucci’s having observed Native Americans chewing a certain green plant. “This book remains the earliest printed reference to tobacco, and the year 1507 became for Arents the starting point of his collection,” explains Bartow.

From the 16th century onward, the use of tobacco, unknown to the world outside the Americas, spread eastward. Tobacco’s history, culture, use, and economy have become worldwide in the nearly 500 years since the plant’s discovery, and it was the written, painted, printed, etched, and manufactured tangible history of the subject of tobacco that fascinated and inspired George Arents to comb the world for his collection.

By the time Arents began his collecting, the number of books and objects relating to tobacco was already immense. It was necessary, therefore, for Arents to limit his collecting to what was both rare and – true for all collectors – what was interesting to him. Before Arents, there had been no systematic collecting of tobacco-related material, but with his passion and his fortune, Arents was able to accomplish this in 50 years. By 1952, five great illustrated volumes were published on the collection, and are themselves a monument of tobacco history: “Tobacco, its History Illustrated by Books, Manuscripts, and Engravings in the Library of George Arents, Jr.”

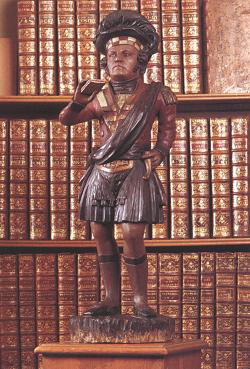

While Arents’ collection would ultimately contain thousands of volumes related to every aspect concerning tobacco, it by no means developed into only a library of books. Arents’ son, while driving in New England, spied a cigar store Indian which now is one of a pair – “he Squanto, she Pocahontas” – that greet visitors on their entry into the reading room.

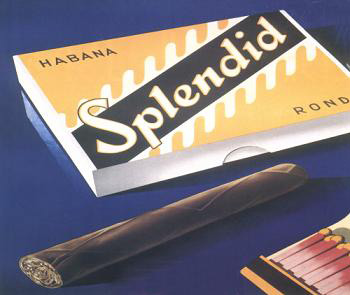

Hans Neukmann, Habana Splendid poster (no date)

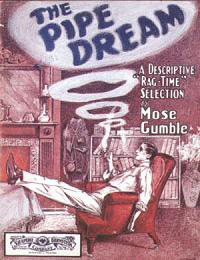

Systematically and endlessly, Arents carefully acquired items of every imaginable variety and use. There are 18th century snuff vending machines and tobacco pouches, as well as storing and carrying containers of many varieties from numerous periods in history. Sheet music, with allusions to smoking, art prints from the Renaissance to Monet and Van Gogh, picturing every aspect of smoking and chewing and sniffing tobacco, abound. The collection contains many thousands of cigar box labels and bands, as well as letters, manuscripts, and everything related to tobacco and smoking that delighted his fancy – and now ours.

As curator, Virginia Bartow, along with every curator since Arents’ death in 1960, has added to the Collection, keeping it current. “Every work must have some link to tobacco,” she indicates. And this relation is apparent, for instance, in a series of photographs portraying smoking writers, artists, and musicians, such as Peggy Lee and Bob Dylan.

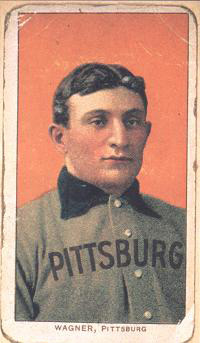

Original Honus Wagner baseball card

The front reading room at the New York Public Library was in fact designed to complement the library in Arents’ Westchester home, and was constructed in 1943 when the collection came to the Library. The walls are lined with bookcases, and a number of objects are displayed as decoration. They include the aforementioned cigar store Indians, and a rare figure of a Scotsman holding a snuff box, which had originally been a street sign. The figure is rare because most such signs were destroyed in 1745, during the Scottish Rebellion. There are European and American tobacco pots, rasps, drying forms, humidors, pouches, and a plethora of pipes. There is one of 40 or so meerschaum pipes once owned by the writer Amy Lowell, although she herself was only known to smoke cigars. Less exotic, but more expensive, is an original Honus Wagner baseball card. A pristine example of the same card fetched over $450,000 at auction a few years ago, when purchased by hockey legend Wayne Gretzky and then Los Angeles Kings owner Bruce McNall. These cards were originally given out as premiums in packs of Sweet Caporal cigarettes. And there is a quaint little brass box which opened, several centuries ago, at the drop of a penny, to dispense a pinch of snuff. Speaking of snuff, we also find the pewter snuff box that Charles Dickens carried with him on speaking tours.

A rare figure of a Scotsman holding a snuff box

That Shakespeare never mentioned either tobacco or smoking (although the pipe was already flourishing in his day), was a fact that proved initially frustrating to Arents. However, he was more than able to satisfy himself with the countless allusions to the happy habit occurring in other literature. While it would be impossible to list even a fraction of these works, Arents purchased many unique items, such as James the First of England’s “Counterblaste to Tobacco,” of 1604 (a copy of which took Arents 30 years to find). There are thousands of examples in general and fictional literature in both printed and manuscript form. The collection includes both the handwritten manuscript and original typescript of Oscar Wilde’s, The Importance of Being Earnest, which contains the wonderful scene between Worthing and Lady Bracknell, where she grills him unmercifully to determine his matrimonial suitability for her daughter. Questioned about whether or not he smoked, Worthing replies in the affirmative. “I am glad to hear it,” she counters. “A man should always have an occupation of some kind.” It’s perhaps one of the most famous, and surely one of the funniest, literary allusions to smoking. Additionally, there are works by Shaw and Waugh and Faulkner, among others, representing the literature of this century. The collection now contains over 10,000 books and 1,000 manuscripts of every conceivable variety and interest – all with mentions of tobacco or smoking.

[HTML1]

Although Columbus mentioned smoking in his journal, he did not know what tobacco was called. One can discover this by visiting the collection and researching any area of interest or pleasure. For example, there is a letter written by George Washington in 1762 discussing a shipment of his tobacco, or writings of Thomas Jefferson, whose wealth also derived from the sale of tobacco. Arents once said in a lecture, “Where there’s smoke, there’s literature.” And a friend once told him, “If I had a library like yours, I’d puff with pride.” Although Arents was passionate about tobacco and everything related to it , he never smoked!

Continuing our research, we learn that smoking was probably introduced to Europe by Sir John Hawkins, who returned to England after he and his men, while on an expedition to Florida, saw French colonists smoking the weed. This would make the Sunshine State the first American destination for smoking European visitors. The French obviously liked it, for they have been smoking heavily ever since.

But it was initially in England where tobacco, following a brief period of belief in its medicinal properties, had its most extensive use. Jerome E. Brooks, the author of the original five-volume catalogue, wrote in the Library’s “Bulletin” in January 1944, about the developing trend of English pipesmoking: “The smoking habit, by the early part of the 17th century, had developed into a national recreation … the impetus to the habit, after it had become pretty well established in seaport towns and among English mariners, was given to Sir Walter Raleigh. He introduced neither the plant nor the custom into England, but he was the first advertiser on a national scale of the joys and benefits of smoking, and his encouragement of the habit added a host of smokers to the then small ranks. He’s said to have taught Queen Elizabeth the proper use of the pipe, and his literary friends and associates furthered the cause of their favorable reference as a beneficial social pleasure.”

One of writer Amy Lowell’s meerchaum pipes

Initially in 1943, and until his death in 1960, George Arents continually donated new works to this unique treasure trove at the library, which was conveniently across the street from his office. He dropped in most days to visit his collection, as we may do ourselves when the spirit so moves. But first, tap out your pipe before entering.

PipeSMOKE – Spring 98

That is a great read Kevin, thanks for reviving it

Excellent morning read. Thanks.

As a follow-up, here is a link to some digital scans of his collection of artwork.

http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/dgdivisionbrowseresult.cfm?div_id=hsa

Another must see place in NYC.

Gotta keep this on the down low less the smoking Nazis decide to purge the collection for the good of the children.

An amazing place and an amazing description of such a vast array of a collection.

Wow kevin thanks for the history read loved it.

Much thanks to Alan Schwartz & Kevin Godbee for making these archived articles available to us.

+1 petergunn. Wouldn’t that be a tragedy? Great article Kevin. Thank you

Enjoyable read indeed.

Many thanks.

well kids pack your bags daddy is taking us to new york

I finally have a reason to revisit the Big Apple!

The article implies that you can just wander into the room housing the Arents collection and take a gander. Maybe I’m reading a bit too much into it, or maybe restrictions were different 16 years ago when this article was published, but nowadays getting in is a more involved.

If you’re from out of town you have to register in advance, answering all sorts of nosy questions to establish bona fides and tell them exactly what you want to do in there (if you’re local you can sometimes register on the spot, but the book you’re looking for may not be readily available). Then when you arrive you find that the door is kept locked; you have to knock discreetly and hope that one of the attendees can hear you and lets you in (the password, by the way, is “swordfish”).

Once inside you show government issued photo id, sign some paperwork, and wait for them to fetch whatever it is you want to look at. Depending on the book, they’ll offer you pencils (no pens are allowed), a cloth covered weight to gently keep the pages open, and I think white gloves (I’m not sure about the last; it’s been a couple of years since I visited).

Oh, and if you cough too loudly they beat you senseless with a small lead statue of Alfred Dunhill. Just kidding about the last part; or I think I am. I never wanted to take the chance of coughing and find out.

All in all an amazing collection, and a neat experience visiting the room in which it’s housed. But seriously it’s a bit more complicated than just wandering inside on a whim.

Thanks for re-posting this very interesting article. 2 questions though, Arents paid $2.25 for a pamphlet in 1893? That would have been a small fortune, no? And #2, I’d like to read more about the antique snuff vending machines, any tips as to where to search?